I recently unveiled a new tier of Patreon rewards: 3D printed shark and ray models!For $17 per month, you will get a monthly 3D printed educational model of different shark or ray parts in the mail, and you’ll be supporting my efforts to provide these models to schools for free.

This month’s reward is the barb from a Pacific Cownose Ray, Rhinoptera steindachneri. This particular specimen is a part of the Texas A&M University Biodiversity Research and Teaching Collection, and was scanned as part of the #ScanAllFishes project!

This month’s reward is the barb from a Pacific Cownose Ray, Rhinoptera steindachneri. This particular specimen is a part of the Texas A&M University Biodiversity Research and Teaching Collection, and was scanned as part of the #ScanAllFishes project!

I reached out to Heather Prestidge and Kevin Conway, curators of the Texas A&M collection. They told me that this particular specimen was collected in 1993 by John McEachran (author of the multi-volume “fishes of the Gulf of Mexico“) and Janine Caira (now a parasitologist at UConn). It was collected in Baja California, Mexico. Heather was pleased to learn that I was using their specimen for this project, and said “our specimens have an unlimited number of uses even after their primary project!”

Here’s a picture of another specimen of the same species from this collection, you can see why they’re sometimes called “Golden Cownose Rays”.

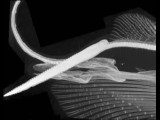

Here’s a CT scan focusing on the barb, from the Virtual Natural History Museum.

Learn more about the Pacific cownose ray and the science behind stingray barbs below!

- Rays are cartilaginous fishes just like sharks, skates, and chimaeras. That means that their skeletons are made not out of bone, but out of cartilage (the bendy stuff that’s in our ears and noses). According to the latest guidebook, there are described 633 species of rays, which are in 26 families. Not all rays are stingrays- in fact, this group of fishes also includes manta rays and sawfish! And in case you’ve ever wondered what the difference between a skate and a ray is, here’s a great answer from the Florida Museum:

“The major difference between rays and skates is in their reproductive strategies. Rays are live bearing (viviparous) while skates are egg laying (oviparous), releasing their eggs in hard rectangular cases sometimes called “mermaid’s purses”. Also, skates typically have a prominent dorsal fin while the dorsal fin is absent or greatly reduced in rays.Most rays are kite-shaped with whip-like tails possessing one or two stinging spines while skates have fleshier tails and lack spines. Rays protect themselves with these stinging spines or barbs while skates rely on thorny projections on their backs and tails to for protection from predators. Skates have small teeth while rays have plate-like teeth adapted for crushing prey. Another difference is that rays are generally much larger than skates.”

2. Stingrays can only use their barb defensively, which means there’s really no such thing as a “stingray attack.” According to the American Museum of Natural History, “When triggered by pressure on the back of the stingray, the tail is suddenly and powerfully thrusted upward and forward, into the victim, which makes the stingray dangerous only if stepped on.” Claims that Steve Irwin, perhaps the most famous victim of a stingray’s barb, was “stabbed hundreds of times” are just not biologically possible.

3. I asked Dr. Christine Bedore, an assistant professor of Biology at Georgia Southern University, about ray barbs. Here’s what she had to say:

“The barb differs in morphology among species- some species have shorter barbs and some have serrations, similar to a kitchen knife. Although barbs, when present, are always located on the tail, they may be at the base of the tail where it meets the body or they may be halfway down the tail. Stingers that are in the middle of the tail are easier to get stung by.

Barbs typically have venom, in addition to the sharp stinger. The venom on the stinger is produced by a venom gland in the skin of the tail. Some species have fairly weak venom, so most of the pain associated with being stung is from the wound itself. However, some species have stronger venom, and the pain associated with the venom may be felt throughout the appendage that was stung (e.g., throughout the entire arm or leg).

Stingers are shed as they get old and a new one grows in its place. Sometimes when a stingray uses its stinger for defense, the stinger breaks off, but the stingray will grow a new stinger. Some, like eagle rays, may have 5-6 stingers that are stacked on top of each other. The new one grows underneath the old ones.” – Dr. Christine Bedore

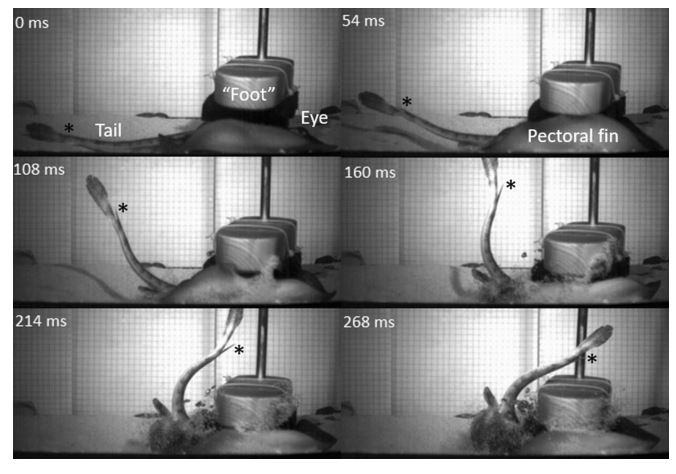

Here’s what it looks like when a stingray stings, from this paper.

4. Stingray stings are very rarely fatal. In fact, there have been fewer than 30 stingray-related fatalities that have ever been recorded! The few fatal stings are generally the result of the barb piercing someone’s heart, as happened with Steve Irwin, or as a result of the puncture wound getting infected. However, stingrays do cause lots of injuries– hundreds each year in the United States alone! John Smith (of Pocahontas fame) was stung by a stingray, and there’s still a “Stingray Point, Virginia” named in honor of this. In Greek mythology, Odysseus was killed by a spear tipped with a stingray barb. I was stung in the foot by an Atlantic cownose ray (the barb went right through my work boot), and I can confirm that it hurts a great deal!

5. Rays are actually more threatened as a group than sharks are! According to this open-access research paper led by my PostDoc advisor Dr. Nick Dulvy, of the 7 most threatened families of chondrichthyan fishes, 6 are rays and only one is sharks! The Pacific Cownose Ray’s Atlantic ocean cousin is a focus of some interesting ongoing conservation efforts. After a famous paper claimed that the loss of sharks led to cownose ray population explosions (incorrectly, as it turns out) , fishermen began targeting cownose rays- and these rays just can’t support a fishery since they only have one pup a year! I asked Sonja Fordham, the President of Shark Advocates International, to describe this conservation issue, and here’s what she said:

“Cownose rays are probably among fishermen’s least favorite elasmobranchs. This schooling species is typically not valuable enough to keep, and a pain to release. Shellfish growers are bothered when rays feed on the spat they’re trying to cultivate; their anecdotes help to fuel misperceptions that they’re also scarfing up all the wild oysters, scallops, and clams. Collective industry distain has led to culls, market development, and recreational killing contests — all despite cownose rays’ exceptional susceptibility to overfishing. Unlike most other fish, however, cownose rays have a wildly different and positive public image, thanks to their starring roles in aquarium touch tanks and their tendency to appear kind of “smiley.” Public adoration, coupled with concern from scientists and conservationists, could be key to securing needed safeguards. Pleas for protections need to get louder though, as these vulnerable rays continue to be killed, essentially without limit.” – Sonja Fordham

Want to get your own model Pacific Cownose Ray barb? Support me on Patreon! This reward is only available to US residents, but other rewards, including exclusive access to my shark science and conservation newsletter, are available to all.