A lot of debate among conservationists centers on the conflict between the desire to see a species totally protected from human exploitation and the reality that market forces will continue to exist (see the latest on shark fin bans for a very good example). Ideally, a conservation plan should strike a balance, ensuring the continued existence of the species while still allowing people to profit from it in some way. This also requires a clear idea of the limitations of conservation policies. For example, US policies (even the mighty Endangered Species Act) only directly affect populations within the territorial waters of the United States, while international agreements like CITES restrict trade of the species without telling any particular country what to do domestically. However, there are ways to track the interaction between conservation policies and the market, making it possible to make some predictions on how things like fishery management plans and CITES listings might affect trade. Then it gets interesting. Armed with this knowledge, can the market be pushed towards species conservation?

A new paper by Dell’Apa et al. in the journal Ocean & Coastal Management (referred to as Dell’Apa et al. 2013 from here on in) looks at the domestic fishery management and international trade of spiny dogfish sharks to try and tease out the effects of management policies on the international trade of this species. First, a little background. Spiny dogfish are the most heavily-fished shark in US waters, and showed signs of population decline in the mid-late ’90’s. As a result, a fishery management plan (FMP) was developed for the species that slashed quotas and enacted other tough measures. The dogfish stock along the US east coast responded better than anyone could have predicted, recovering in less than 10 years. The dogfish fishery continues to this day, with low quotas and daily trip limits (though these seem to go up significantly on an annual basis).

While all this was happening, spiny dogfish came up twice for CITES Appendix II listing, including last-second support from the US in 2007 that encountered heavy resistance from both fishery management agencies and commercial fishing groups at home. Both proposals were rejected. Shortly after the dogfish recovery, fisheries in the US and Canada were certified as “sustainable” by the Marine Stewardship Council. It’s been a long, strange trip for spiny dogfish management.

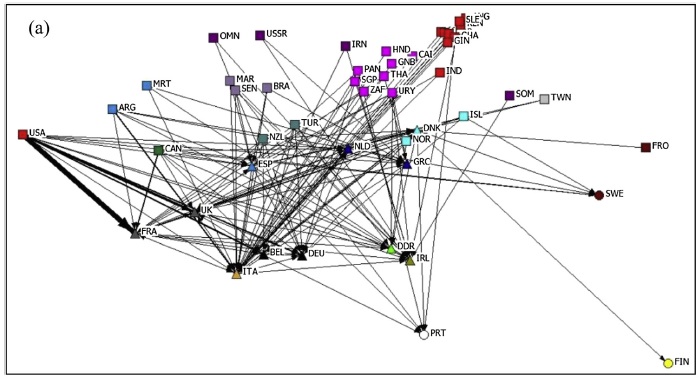

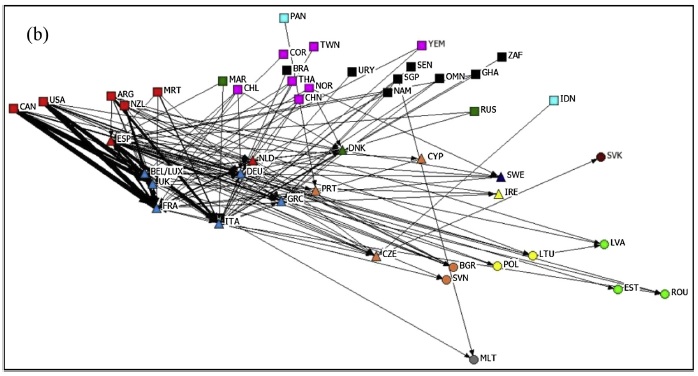

Most spiny dogfish demand is based in the European Union, with dogfish-fishing nations mainly exporting their sharks to the EU. Using network analysis methods, Dell’Apa et al. (2013) were able to figure out which countries were importing and exporting the most dogfish and who their trading partners were. They were also able to break this up into periods before and after the dogfish FMP was developed and implemented in the US. The results, while not necessarily surprising, are interesting to see.

The network maps above show that the development of an FMP for spiny dogfish in the US had considerable effects on the international trade of the species by reducing the sheer volume the US could contribute. This in turn drove up demand and allowed other countries to get involved. Interestingly Spain, primarily an importer before the FMP, switched gears and became a major exporter within the EU. Of the major dogfishing countries, only Canada and the US have official management plans for the species (this is why Canada is included with the US in the MSC certification).

At first this seems like a no-brainer, and something that any anti-regulation activist would trot out: managing the fishery actually decreased US market share internationally. However, there is an extra piece that could be added that would put the US (and our friends to the north) back on top, and it’s another conservation measure. CITES Appendix II requires that those engaging in international trade of a species must demonstrate that their exploitation of that species doesn’t put it at risk of extinction. It’s hard to argue that the US FMP was not successful in halting the decline of spiny dogfish, and the MSC would seem to agree. This means that if spiny dogfish were to be listed as an Appendix II species, only the US and Canada could export them until the other dogfishing nations get their act together with effective management plans.

It’s basically like saying that only fair-trade coffee is legal to sell and being the only coffee shop in town selling fair-trade coffee. By getting spiny dogfish Appendix II listed, we would not only cause the value of our fishery to skyrocket in the short term (and get rewarded for good behavior), but would create an economic incentive for dogfish to be fished responsibly worldwide. I’m sure this won’t impress the “no shark fishing ever” crowd, but that kind of direct economic benefit for responsible resource use is extremely hard to find, and should be embraced whenever possible. I hope Dell’Apa et al. (2013) gets as widely-read as possible, and comes up in the conversation the next time CITES rolls around.

Full disclosure: Andrea Dell’Apa is a labmate of mine and a frequent research collaborator.

Update 05/20: Corrected some of the history of spiny dogfish proposals at CITES and subsequent MSC certification. Thanks to Sonja for setting me straight there.

Source

Dell’Apa, A., Johnson, J., Kimmel, D., & Rulifson, R. (2013). The international trade and fishery management of spiny dogfish: A social network approach Ocean & Coastal Management, 80, 65-72 DOI: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2013.04.007

Glad to hear the paper is out. I look forward to reading it. In the meantime, re: this blog post: I agree that CITES App II offers substantial benefits for both spiny dogfish and countries that manage the species. The US, however, did not “join in” in the EU proposals to list the species under CITES. In 2007, the US decided to vote ‘yes’ at the very last minute (during the CoP), and did not support the listing in 2010. Other countries with about as much management as the US and Canada (quotas) include New Zealand and the EU (EU TACs set at zero now, but that can change). Countries can trade in App II listed species if they find “non-detriment” (for which they have some latitude). MSC certification has been granted for Canadian fisheries only on the west coast and for US fisheries only on the east coast. (Lack of cooperative trans-boundary management for straddling stocks did not prevent MSC approval). I can’t agree that the US Atlantic spiny dogfish quota is still “low” as it is now 10 times what is was five years ago and dwarfs quotas for any other US shark. In any case, spreading the appreciation that people increasingly demonstrate for bigger sharks to include smaller species would seem to be an important step for securing a spiny dogfish CITES listing in the future.

Thanks for setting me straight on CITES and MSC history, Sonja. This is what happens when I try to post between check-out dives…

I agree that the annual jacking-up of the dogfish quota is a cause for concern. That said, the population of spiny dogfish (even after their late-90s slump and accounting for the upcoming dip) is naturally much higher than that of the coastal shark species (with the possible exception of sharpnose and smooth dogfish), so any coastal shark quota should be considerably lower than the dogfish quota. Also, with only two processors on the east coast, it’s possible that the higher quota will continue the glut (and resulting low market price) and keep fishermen from ever actually hitting that quota. This year’s dogfish season will be a test of that, though I’d definitely prefer management to reflect a more cautious approach in the first place.