Although marine fish face many threats, one of the greatest is large-scale modern commercial fishing. Technology makes it all too easy for so-called “factory ships” to remove enormous numbers of fish from the oceans, sometimes with devastating effects on the populations of those fish and their habitat.

Marine conservationists have proposed a variety of policies to protect fish populations around the world. Of these, the concept of the marine protected area (MPA) is arguably the most popular. Though technically a marine protected area is any area of the ocean where human activities are restricted in some way, the best known version is an area where fishing is banned with the goal of letting exploited fish stocks recover.

Unsurprisingly, such MPAs aren’t politically popular. People don’t like it when the government tells them that they can’t do something, particularly when that something is how they earn a living.

Can MPAs help fish?

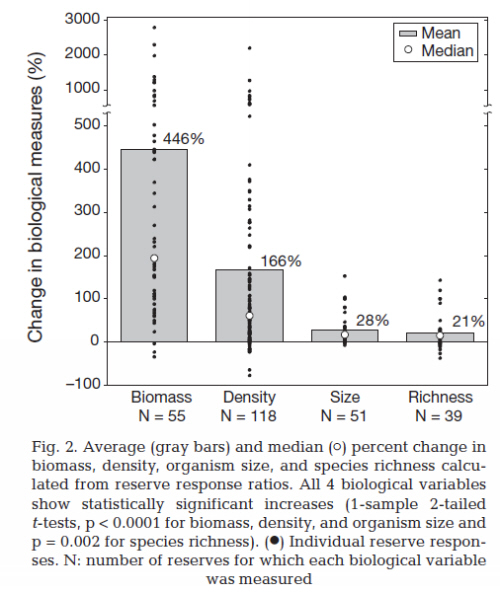

From a pure conservation standpoint at least, you can’t argue with the results. A meta-analysis of 124 restricted-fishing (to various degrees) MPAs in 29 countries found that while the magnitude of each change varied a great deal, in nearly every case the area inside the MPA had more animals, larger animals, and more species of animals than the area immediately adjacent to the MPA. Encouragingly, these effects can occur within a few years, and they appear to last as long as the MPA exists. Even a small MPA can make a big difference.

The results of this meta-analysis provide strong evidence indicating that when fishing is restricted, fish populations will increase. In other words, “duh”. While it’s nice to see such powerful evidence that MPAs are nearly always effective, these conclusions aren’t really surprising. It makes total sense than when the primary threat to a population is removed, that population will increase. It’s another claim by MPA supporters that is only recently gaining broad acceptance- the claim that closing some areas to fishing will actually benefit fisheries.

Can MPAs help fishermen?

There are two components to the counter-intuitive claim that restricting fishing can help fishermen. The first, called “adult export”, basically states that once there are too many fish in an MPA, some adults will leave the MPA in search of less crowded habitat. These fish can be harvested by fishermen. The second, called “larval export”, states that fish in an MPA will mate and their larval offspring will be carried out of the MPA by currents. These larvae will colonized somewhere else, grow up, and can be harvested by fishermen. Until recently, there was limited evidence for either of these claims, which led to numerous critiques and a lack of widespread acceptance. Powerful new evidence changes all that, but before we get to it, let’s address some of the criticisms.

It’s important to note that MPAs really only work for non-migratory species. If a fish moves outside of the protection of the MPA, then it’s susceptible to fishing pressure and the MPA didn’t do it’s job. This concept is the part of one of the most influential critiques of the “MPAs can benefit fisheries” claim. Robert Shipp performed a detailed analysis of all of the major U.S. fisheries and concluded that MPAs would not help their recovery.

First, Shipp correctly pointed out that if fish stocks are already healthy, they don’t need to recover and MPAs therefore aren’t appropriate for them (which he claims is the case for the majority of fish species- he wrote that “of landings in 2001, 75.9% of stocks of known status were not experiencing overfishing and 63.7% were not overfished.” He then stated that if animals don’t remain in the MPA, it won’t protect them and therefore MPAs are useless in their case. In other words, MPAs are most useful in aiding the population recovery of heavily exploited non-migratory species.

Of the “major fisheries” in the U.S. (14% of stocks that accounted for 99% of landings in 2001), Shipp concluded that a grand total of zero of them would benefit from MPAs*. All of the major fisheries are either not overfished, already have effective recovery plans in place, or consist of highly migratory species like tuna.

Shipp also tried to shoot down the concepts of adult and larval spillover. He acknowledged that MPAs are effective at increasing fish population size within their boundaries, but points out that “this portion of the stock has been removed from the harvest”- in other words, from a fisherman’s perspective, the fish might as well not exist because the fisherman can’t catch them. He claims that adult spillover from an MPA “will always be less than that of a properly managed stock” in a non-protected area”, and that larval spillover “may be beneficial, but only for a seriously depleted stock” because “larval production…does not normally relate strongly to year-class strength”. You can feel the frustration of a scientists tired of making what he perceives as a basic point when he writes “this principle has been the subject of scores of books and thousands of publications since it was espoused nearly 150 years ago by Darwin”. Oh, snap!

Is this paper proof that MPAs are ineffective and shouldn’t be used for fisheries management? No, not really. Though Shipp provides a refreshingly different perspective and makes some valid points, there are several major flaws in his reasoning. Yes, if a fish leaves the protection of an MPA is is vulnerable to fishing. However, a cleverly-designed network of MPAs based on the migration patterns of a fish can protect it for large portions of its life, and some protection is a lot better than none at all.

Yes, most U.S. fish stocks aren’t “overfished” or “experiencing overfishing”, but these are legal words with specific definitions. Using them hides that many species have suffered serious population declines, and it omits non-target “bycatch” species, many of whom have also declined in population. Also, using only the “major” fish stocks omits 86% of harvested species in the U.S. from his analysis. They may not be as economically important as tuna, but fishermen depend on them, too.

Yes, adult spillover from an MPA will result in less yield than a well-managed fishery, but it will result in much more yield than a poorly managed fishery that collapsed. Shipp would also do well to keep in mind that fish inside an MPA are much larger than those outside, and for some fisheries catching fewer larger fish can be the economic equivalent of catching more smaller fish.This principle may not support supertrawlers and factory ships, but it can likely support coastal fishing fleets. It can also benefit charter boats, whose hires only want to catch a few big fish to begin with.

With all due respect to Robert Shipp and Charles Darwin, while larval production may not be related to year-class size, it’s undeniably related to the size of a female. For example, one 24-inch vermillion rockfish has more eggs than 17 14-inch-ers. Recall that female fish are larger inside MPAs than outside, and some of your confidence in MPAs should be restored.

New evidence of “larval spillover”

With the major criticisms of MPAs out of the way, let’s discuss an exciting new paper and the evidence for larval spillover that it presents. Adult spillover is relatively easy to prove (we’ve been able to tag and track fish for decades) and has been demonstrated worldwide, but the larvae of many species are so small that they’re almost microscopic. Saying “it’s incredibly difficult to track millions of tiny fish in the open ocean” may be one of the biggest understatements I’ve ever written. The best way to do it is by proxy through the use of complex genetic tools, specifically parentage analysis.

Parentage analysis is complex, but basically if you know the genetic makeup of a community’s adults and you test the genetic makeup of offspring, you can determine who the parents are. If the genetic makeup of offspring matches that of parents that live far away, larval dispersal can be inferred. That’s exactly what Oregon State researchers did with yellow tang in Hawaii.

I actually was talking to some researchers from Auburn recently (yes, they yelled out “War Eagle” on multiple occasions) who found kind of a novel way to figure out whether artificial reefs benefit red snapper production. I’m fuzzy on the details, but they used age and growth data to match up year classes of snapper with the age of the reef.

This seems like it would be more conclusive with more “resident” species. That said, coupled with genetic analysis, do you think this might be a way to approach measuring fish production from MPAs? Maybe a way to kind of “ground truth” the genetics?

Nice article David. While I know that the focus of these research studies has been on finfish, but those are not the only exploited fisheries in the US. There are numerous fisheries that are shellfish. Many of these species are not migratory, and having a series of reserves can greatly benefit populations and catch. So while they may not be a benefit to all species, there are a number of species they could benefit, if implemented properly.

Absolutely true, John. There’s a lot of evidence that the scallop fishery in particular has benefited from MPAs.

Good write up, although i would like to point out/expand on a couple of things.

1) MPA’s can still benefit fish that are wide ranging. For example, many teleosts and sharks use specific spawning/pupping areas, and even if just these locations are protected then the species is provided some protection.

2) Adult spillover is not easy to quanitfy. It is in fact notoriously difficult to differentiate true spillover (where animals shift their movements or home range outside of the MPA due to density-dependent factors) from simple home ranges that happen to intersect the MPA boundary. A tracked fish crossing the MPA boundary may simply have a home range that includes habitat outside the MPA.