In The Mass Extinction of Scientists Who Study Species, Dr. Craig McClain argues that we are loosing a fundamental unit of biological science – the Taxonomist. He’s right, of course. Taxonomy is a shrinking field. Entire phyla sit, unstudied, as the expertise necessary to understand them retires and expires. With few to train the next generation of taxonomists, the field could slowly vanish. Molecular tools are supplanting traditional taxonomy (once described to me as “the ability to identify hundreds of species of centimeter-long worms by counting ass-hairs under a microscope”) as the de rigueur method for identifying organisms.

In The Mass Extinction of Scientists Who Study Species, Dr. Craig McClain argues that we are loosing a fundamental unit of biological science – the Taxonomist. He’s right, of course. Taxonomy is a shrinking field. Entire phyla sit, unstudied, as the expertise necessary to understand them retires and expires. With few to train the next generation of taxonomists, the field could slowly vanish. Molecular tools are supplanting traditional taxonomy (once described to me as “the ability to identify hundreds of species of centimeter-long worms by counting ass-hairs under a microscope”) as the de rigueur method for identifying organisms.

I do not disagree with Craig. Losing skilled taxonomists is tragic for the biological sciences. Unlike many leading the charge in support of taxonomy, I did not benefit from a rigorous taxonomic study in my early career. I fall into the same camp as Dr. Holly Bik, relying primarily on molecules, not morphology, to draw the distinctions between my samples. I never identified species by counting the ass-hairs on a worm, and my education is poorer for it.

There are deeper issues at stake here though, because, as Craig said, we are in the middle of a biodiversity crisis, and without taxonomists, we’ll never know how many species we’ve lost. Here I must finally part ways with McClain, because while the practice of taxonomy is fundamental to understanding the present shape of the living world, it lies far from the heart of conservation. ‘Species’ is a notoriously difficult concept. There is no one definition of ‘Species’ that fits all cases. Before we can begin to address the effect of the taxonomy drain on conservation biology, we have to wrestle with some fundamental and difficult questions. Although I am trying to find an answer, realize that these are not the kinds of questions that have concrete answers, but serve as a launching point for a larger conversation about conservation.

What is the fundamental unit of conservation and where do species fit into that framework?

The ‘Species’ Concepts

Several problems emerge when discussing species. Species as a word has both semantic and functional uncertainty (in order to avoid some imprecision, I will use ‘Species’ to refer to the concept and species to refer to specific biological entities). In a 2003 paper, Hey et al. present three semantic issues inherent in the term species:

(1) ‘species’ is the name of a taxonomic rank; (2) ‘species’ is the word that we apply to a particular taxon of that rank (e.g. the species taxon Homo sapiens); and, finally, (3) ‘species’ is a word that we apply to an evolving group of organisms.

Hey et al. 2003

Due in part to the above points, there is often confusion, even among scientist, regarding what “species” someone is referring to. But beyond semantic issues, they are real, fundamental disagreements concerning what actually constitutes a species. Even within the framework of a single ‘Species’ concept, opinions vary from scientist to scientist regarding where to draw the species boundary. A taxonomist may be more willing to lean on morphology, while a geneticist may prefer to look at the genetic code. What one person may consider a significant morphological trait may be regarded as inconsequential by another. When we begin to enter into systems where we cannot make direct observations, the classifications get even more hazy. Where is the species boundary for Escherichia coli where individuals may be genetically diverse and freely exchange acquired genes like trading cards? As molecular tools improve, we’ve begun to find cryptic species who are morphologically indistinct. Much of what a species is depends on the observer.

Because of this ambiguity, numerous ‘Species’ concepts – from the classic biological ‘Species’ concept to more modern idea such as the Evolutionarily Significant Unit – have emerge in an attempt to shine light on this problem. A recent count put the number of different ‘Species’ concepts at more than 24. These run the gamut from purely ecologic definitions, to definitions that attempt to incorporate some evolutionary history, to purely phylogenetic definitions. All species concepts are united by basic principles of evolution – some organisms diverged more recently than others and are thus more closely related. DeLene Beeland has a nice summery of the ‘Species’ problem, as a review of arguably the best recent text on the topic, at Wild Muse.

Cryptic species throw an additional wrench into the ‘Species’ problem. Cryptic species are morphologically, and in most cases, ecologically, indistinguishable from one another. They look the same, act the same, and occupy the same niche. However, they are genetically distinct from each other. Cryptic species may emerge when populations become isolated from one another, when seasonal migration or breeding rhythms become decoupled, or for a host of other reasons. In many cases they don’t fit any ‘Species’ concept. They may very well be a single species in the process of becoming several, sitting at fork where two paths split, clearly demarcated, yet still connected.

The challenge that all ‘Species’ concepts try to rise to is in connecting definite categories that we use to understand the current state of the natural world with the indefinite and constantly fluctuating evolutionary history of life. For an inverted example of this, consider it akin to calling everyone who currently lives in the United States of America as “American” while ignoring the rich history that led all these disparate people to this piece of land. You would be technically correct, but ignoring a much deeper and more profound story.

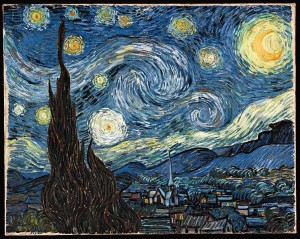

The grand irony of the ‘Species’ problem is that it is not a biological problem. In general biologists understand how evolution works, how these wonderful pieces of life on earth fit into the grand picture. Species are not formed of pointilist reduction, but swirl together, sometimes distinct, sometimes not, an ever-expanding, ever-changing starburst in the night sky.

‘Species’ is a categorical problem. It relates to how we perceive and interact with the world we currently live in (I am intentionally avoiding discussing ‘Species’ as it pertains to fossils). While it is essential to understand not just what a species is, but under what criteria that species was determined, these distinctions should not be at the heart of conservation. Biodiversity is not measured in number of species alone and the current Biodiversity Crisis is much bigger than simply losing N species.

In the next few posts, I’m going to argue that conservation initiatives have, in many cases, been set back by a strict, species-based management approach, and that failure to recognize ‘Species’ as a human construct has contributed to biodiversity loss. Finally, I will argue that conservation as a whole could benefit from a post-Impressionist species concept.

Jody Hey (2001). The mind of the species problem TRENDS in Ecology and Evolution, 16 (7), 326-329

Jody Hey, Robin S. Waples, Michael L. Arnold, Roger K. Butlin, & Richard G. Harrison (2003). Understanding and confronting species uncertainty in biology and conservation TRENDS in Ecology and Evolution, 18 (11), 597-600

Thanks for the holistic view. Biologist Paul Ehrlich used an analogy of thinking of species loss like a plane wing kept in place by a large number of rivets. The loss of one rivet is of no great consequence to the wing. If two and three go, the wing will likely still resist failure. But if the process continues, eventually one critical rivet will be lost, the wing will break off, and the plane will crash. It is likely that not all rivets are equally important in keeping a wing intact. How many and which of them can be “sacrificed” is generally unknown. Ecosystems function in much the same way.

Interesting overview. I’ve been wondering if it might not be advantageous for conservation movements to switch to a niche-and-genetics-based system of defining an extant species. Unfortunately, it looks like conservation might benefit from doing a bit of triage that way…

I look forward to part 2.