This past weekend, the shark cull officially began in Western Australia as the first shark was killed. The scientific evidence is clear that culls do not lessen people’s risk of shark attacks, and more than 100 scientific experts from around the world have signed an open letter opposing this cull. While the only sure way to reduce the risk of a shark bite by 100% is to stay out of the water, there are many strategies that actually can reduce someone’s risk significantly without harming populations of threatened animals.

1) Aerial patrols. Planes or helicopters flying above the beach can help identify when potentially dangerous sharks are present. The Australian Aerial Patrol has done this for decades. Though the spotting rate is relatively low and the patrols are expensive, new technologies like drones can help reduce the cost of these patrols.

2) Shark Spotters. A network of trained staff scan he water regularly and alert lifeguards if a potentially dangerous shark is in the area. This has been successful in South Africa, but is limited by clear water and suitable terrain (i.e. high ground near the water).

3) Close the beaches. If patrols or spotters or any other system identifies that potentially dangerous sharks are nearby, close the beaches to swimming and surfing, or at least warn people so that they can make an informed choice.

4) Designated swimming areas. By enclosing certain small areas, authorities can keep sharks out. Please note that this is different from “shark nets”, which are designed to kill sharks, not exclude them from a small area.

5) Move sharks out of the area and release them. In Recife, Brazil, researchers catch sharks near beaches and tow them out to sea, where they are released. This strategy reduced shark bites by 97% without killing threatened species of sharks.

6) Increased scientific study. Research of habitat use and migration patterns of these species can help reveal times and places when swimmers are more or less likely to encounter sharks.

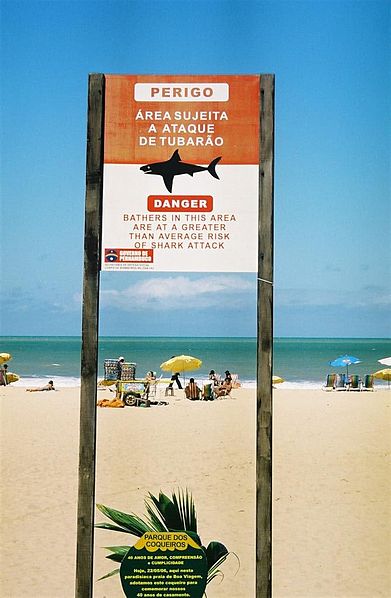

7) Educate people. While there is no way to eliminate risk, people will be safer if they know which behaviors are riskier than others. A public education campaign (including but not limited to talking with locals and signs with information for tourists) would help with this. Public education is by far the most effective way to make people safer.

The government of Western Australia has been made aware of these non-lethal strategies that are more effective at reducing risk, but for now chooses not to embrace them.

Hi David: I agree that the cull is unfortunate at best, and certainly does not help to educate the public about sharks generally or the perceived risk. However, I think you’ve over-stated the scientific basis for your claim that culls do not reduce the risk to swimmers or beach goers. While Brad and his co-authors found no evidence that the State-sponsored fishing for sharks in Hawaii reduced the risk of shark attacks on humans, this is not the same as saying that no culls of any design would reduce that risk. In other words, it’s conceivable that a culling program could reduce that risk, albeit with what I would expect to be severe effects on shark populations and probably ecosystem function. Again, I’m not supporting this approach, but, when you consider how incredibly effective we humans can be when it comes to fishing, I can certainly imagine a shark control program that measurably reduced the number of large sharks. And, this might even reduce the number of attacks, though we both know how difficult it would be to actually demonstrate cause and effect!

This is a great list. Another reason the Shark Spotters program works in Cape Town is because even though the water is not always clean (in fact the average underwater visibility in False Bay, where most of the sharks are seen, is about 5 metres) or calm (it’s frequently very windy, specially in summer), the most prevalent species of shark that could pose a risk to humans, the great white shark, spends quite a lot of time swimming on or very close to the surface, so it can be seen from above.

In Cape Town we also have item (4), the enclosed designated swimming area, on trial at Fish Hoek beach. A shark exclusion net is being tested there until May 2014. It’s highly visible, removed at night to avoid it being fouled by kelp or entangling marine life, and operates in conjunction with a Shark Spotter on the mountain. So far so good – it’s been an excellent effort by Shark Spotters and the City of Cape Town to design and implement a solution that can work in the rough, busy waters here.

Technically, a cull would reduce the risk of shark attack if all the sharks that could possibly get near the beach were killed (not what happened in Hawaii, not what is happening in Western Australia).

David, all good suggestions but your opening statement that “The scientific evidence is clear that culls do not lessen people’s risk of shark attacks” is illogical. e.g. if there are less sharks there is obviously less of a chance of an attack. I think that including such an illogical argument, especially in the opening of the piece, does a disservice to the rest of your logical suggestions.

We should not make policy decisions based on what people who are not experts think sounds like it would work. We should make policy decisions based on the best available data. The best available data (from when Hawaii tried the exact same thing) shows that culls do not reduce the risk of shark bites.

Would painting surfboards & wetsuits so they look less like seals help?

In the UK we have no more wolf attacks, this is because wolves have been hunted to extinction during medieval times. Obviously culling will work if you slaughter the species to extinction. I find it hard to understand why sharks are being victimised for merely doing what’s instinctive to them within THEIR domain.

Ok lets get things into perspective here – the scientists at California have been counting the great whites for 15 yrs and estimate that there are less that 1000 great white sharks left on the planet / the great white is the 5th most dangerous shark to mankind – bull and tiger shark are much more dangerous, especially as they eat mainly turtles that are crunchy – so are humans – while a great white wants mainly blubber, so humans are not on the menu of a great white / great whites are totally nomadic, so what you do in Western Australia will also effect the eco-systems around the world – like South Africa and Brazil / 4 people are munched by sharks per year around the world – while we humans kill 150 million sharks each year for vile shark fin soup industry / there are over 50 shark species that are bigger enough to take a munch out of a person / 99% of attacks happen in only afew metres of sea water / there is new technology that is still being tested – electrical fields being pulsed out by a device on a surfer or swimmer – plus ocean bed devices that do the same thing / scientists at Cape Town are trying all exclusion nets – in other words the holes are so small that no marine creature could ever be caught in these nets and be killed – they are testing this at Fish Hoek near Cape Town – the old shark nets in place at various sights around the planet are indiscriminate killers and should be removed – killing dolphin, turtle, whales and any creature large enough to get stuck in the large gauge nets, plus quite ironically a large number of creatures are caught exiting the beach – thats why the new nets being tested at Cape Town are so important / the ultimate example of the very important role sharks play in the ecosystem is that of recycling life and of keeping our oceans healthy by removing dead and decaying animals like dead whales from the oceans — if i was to be really naughty and cheeky, then i would also mention that 750 people are killed by toasters and 150 people killed by coconuts each year – are we going to suddenly ban them too? no of course not :-))) there are many fantastic people and organisations that are trying their utmost to “understand” shark behaviour – http://www.sharkconservancy.org/ – http://saveourseas.com/ – http://www.threshersharkproject.org/TSRCP/Home.html – and many many others……and the real cruncher to catching large sharks is – they are very slow reproducers and only large and older sharks are mature enough to breed —– i am no scientist, but i am a very keen lover of sharks and moved to Hermanus near Cape Town 10 years ago to see and enjoy nature in all its wonderment – Gansbaai (40mins away from Hermanus) is THE shark cage diving location on the planet. Leave the sharks alone and get out of the water.

David: One of the real strengths of your blog is that you insist on applying good science and logic to your arguments, but you’re slipping up here! Makomike and Carl below seem to agree with me. Risk is the probability of an event weighted against the consequences of that event. All you need to do to reduce the risk of a shark attack is kill one shark. Though, obviously, you’ve reduced that risk a very small amount indeed. The paper you cite does not claim that culls cannot or even do not reduce the risk of attack…the authors found no evidence that Hawaii’s efforts had reduced the risk (as I recall). Again, I’m not claiming that culls are a good solution here.

With the possible exception of catch and release the Australians have tried everything on the above list to reduce shark attacks. I’ve body surfed the beaches in and near Perth, there are clearly posted signs in view to warn all of shark prone waters, and every beach i visited utilized planes and spotters. Australi is a;lso on the front lines of shark research.

I think drones could be a very good option to make beaches safer. Drones would be able to fly over beaches and relay live video of any potential dangerous marine life. Much cheaper in the long run and better positioning than larger spotter planes.

Rule #1: The ocean is the shark’s territory, enter at your own risk. What’s the next step for the Aussies, eliminating everything that is a threat to human life? That’s a tall order…