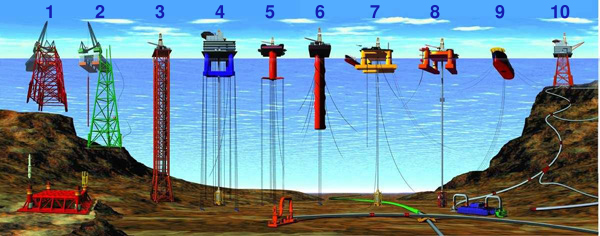

There are currently more than 7,500 offshore oil platforms actively probing the earth’s crust for black gold. Their relatively minimal appearance at the surface belies the shear magnitude of human construction beneath the waves. Oil platforms are among the world’s tallest man-made structures. Compliant tower platforms reach up to 900 meters in depth (in contrast, the tallest building is 828 meters). these rigs are not permanent structures. As the wells run dry and sea water corrodes steel jackets, the wells are capped and rigs decommissioned. At least 6500 offshore platforms are slated for decommission by 2025, which begs the question, what do we do with inactive oil platforms?

There are currently more than 7,500 offshore oil platforms actively probing the earth’s crust for black gold. Their relatively minimal appearance at the surface belies the shear magnitude of human construction beneath the waves. Oil platforms are among the world’s tallest man-made structures. Compliant tower platforms reach up to 900 meters in depth (in contrast, the tallest building is 828 meters). these rigs are not permanent structures. As the wells run dry and sea water corrodes steel jackets, the wells are capped and rigs decommissioned. At least 6500 offshore platforms are slated for decommission by 2025, which begs the question, what do we do with inactive oil platforms?

The now defunct Minerals Management Service devised a seemingly ideal solution; one that would save the oil companies huge amounts of money, pass responsibility of the decaying rigs onto state and federal governments, and create huge amounts of habitat for deep-sea organisms. Instead of removing oil platforms, the Rigs-to-reefs program would knock them over, or leave them standing where they are, creating artificial reefs. Everybody wins, especially oil companies.

On paper, the principles behind using oil platforms as artificial reefs appears sound. We know that fish aggregate around artificial reefs, that hard substrate will be rapidly colonized by invertebrate communities, and that the communities that accumulate around active rigs can be rich in biodiversity. With so many rigs going offline in the next 15 years, it’s hard to argue against their conversion into reef habitat. In the deep Gulf of Mexico, loss of hard substrate has disrupted community dynamics, and the addition of new structures might provide valuable stepping stones for dispersal.

Other artificial reef project have been successful. The Alabama coastline has nearly 20,000 artificial reefs. These reefs, mostly made of concrete, but also old ships, discarded construction equipment, and industrial detritus aggregate fish and have been cited as a major component in snapper and grouper recovery. Artificial reefs are not all good news. Although they provide a boost to fish habitat and subsequent income from fisheries and tourism (including fishing and diving), they also alter community composition and fisheries induced selection.

All of this is compounded by the fact that oil platforms are not pristine environments. While the most obvious and imminent ecologic disruption comes from leaking oil, as we saw during the Deep Water Horizon Disaster that began last April, long term ecosystem damage in the area immediately surrounding the rig is primarily due to the leaching of heavy metals, such as those found in drilling mud, and anti-fouling chemicals. This means that for an artificial reef to be effective, the structure must first be removed from the water and decontaminated, a prospect that will remove the economic benefit to the oil company.

In Louisiana and Texas, inshore rigs-to-reefs programs transfer responsibility for management to the state, absolving oil companies of the heavy cost of clean-up and leaving state tax-payers with the bill. Only 100 rigs have been converted under this program, which is notably unpopular among most stakeholders, oil companies excepted.

There are further questions regarding whether these reefs actually boost fish populations, or act as fish aggregating devices, leaving populations open to continuous fisheries pressure.

The idea to use old oil platforms as artificial reefs is not a bad one, and I can certainly see scenarios in which it could be done effectively. In the current climate of offshore exploration, where accountability is low and shirking responsibility is the name of the game, providing an additional avenue for oil companies to cut corners seems ill advised. Once sunk, there is no practical proposal for long term monitoring and no plan for clean-up if it turns out that these reefs are harmful to the native ecosystem. The deep Gulf of Mexico has always be hard surface limited, and the ecosystem benefits of a rig-reef are low compared to the potential for damage.

If you interested in the type of science/industry cooperative efforts that could provide the rigorous, robust data sets that would be needed to properly evaluate a rig-to-reef program, check out the SERPENT Project.

Macreadie, P., Fowler, A., & Booth, D. (2011). Rigs-to-reefs: will the deep sea benefit from artificial habitat? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment DOI: 10.1890/100112

Mason B (2003). Doubts swirl around plan to use rigs as reefs. Nature, 425 (6961) PMID: 14586435

Interesting post. I would like to have read the paper before commenting, but my institution helpfully only seems to have that journal up to 2008. If anyone’s willing to send me the paper, that would be great!

In any case, I’m not aware of anyone seriously proposing rigs-to-reefs as a viable option in the deep sea. Colonisation of structures is likely to be pretty slow and the habitat value would probably be fairly minimal. Normally when people talk about reefing rigs they’re referring to structures in relatively shallow waters (probably up to about 200m).

I should also point out that any offshore structures already are artificial reefs, that will already be functioning as habitat, and that there could be environmental costs associated with total removal. Total removal of platforms is often assumed to be the best option (environmentally speaking) but there is little evidence that this is true.

There are a couple of statements in your post that don’t really ring true:

“long term ecosystem damage in the area immediately surrounding the rig is primarily due to the leaching of heavy metals, such as those found in drilling mud, and anti-fouling chemicals”

True enough, as it goes, but the structures themselves are not contaminated by the drilling muds – those are already on the seabed. In fact, it could be argued that leaving the structure in place would prevent the ‘drill cuttings piles’ which is where the really nasty stuff is, from being disrupted (for example by trawling), allowing them to degrade naturally over time. Also, while this may vary from place to place, I don’t think that fixed structures are generally painted with anti-fouling coatings. I’ve never heard any suggestion that platforms would need to be brought to the surface and cleaned before being ‘reefed’ – which would be a strange policy in any case, as the main thing that would be cleaned off is the marine life already growing on the platform! In general, as long as the wells are capped properly and the platform topsides removed, the structure itself would be little more than painted steel. The ‘potential for damage’ is rather low, and there are costs (environmental, economic, and safety) associated with removal, especially for larger structures.

“In Louisiana and Texas, inshore rigs-to-reefs programs transfer responsibility for management to the state, absolving oil companies of the heavy cost of clean-up and leaving state tax-payers with the bill”

This isn’t quite true. Operators are obliged to split the cost saving with the state – this money is then available to be used for site management (though admittedly if a major clean-up was for some reason necessary, I guess the state would have to pay for it). Depending on how the reef conversion project goes ahead (in some cases the rigs are moved before being placed on the seabed) the oil company may still be responsible for cleaning up the original site.

There are valid concerns of course (such as the potential use of structures by invasive species). But I would suggest that the actual environmental benefit of removing all existing structures is pretty negligible – and there are possible environmental and safety costs.

Obviously I have quite a lot to say about this, but I don’t want to go on. I would suggest that anyone interested in the subject should check out Milton Love’s research group at UCSB which is a great jumping off point for reading about research into biological communities of platforms in US waters.

Anyone who uses Mendeley might be interested in a reading list I’ve been setting up there, though I haven’t finished populating it with papers just yet. Might find time to do that next week.

Finally, it’s a little picky of me, but it’s a pet hate of mine:

“At least 6500 offshore platforms are slated for decommission by 2025, which begs the question…..”

No it doesn’t

Thanks, great comments. In the paper, one of the proposals is to move existing structures further offshore and depositing them in deep water, so any native community that accrued during operations would be severely disturbed. More to the point, scrapping off everything, including organisms would be ideal, since otherwise we’re talking about potential introduction of invasives into the deep benthos.

Leaving them free standing with the top removed seems bizarre to me, since GoMex doesn’t have natural hard pillars anywhere, which makes them seem more like FAD’s than artificial reefs. Knocking rigs over disturbs the benthic community, and probably disrupts whatever organisms were aggregating there. So I think, with the exception of leaving rigs standing, the pre-decommission reef community is not the same as the post-decommission reef community.

I think environmentally it’s a wash, there are some benefits, and some drawbacks. My bigger concern is oversite and accountability. It seems like an easy way for oil companies to shirk responsibility and abandon old rigs, while taking credit for building artificial reefs.

This entire post is premised on petitio principii, one which you pointed out in your comment.