Last August, two petitions were sent to the National Marine Fisheries Service from three conservation organizations (the Animal Welfare Institute, WildEarth Guardians and Friends of Animals). The petitions (available in their entirety here) requested that four species of skate be listed as “threatened” or “endangered” under the Endangered Species Act, and requested that critical habitat for these species be designated and appropriately protected. These species are the thorny skate, barndoor skate, winter skate, and smooth skate.

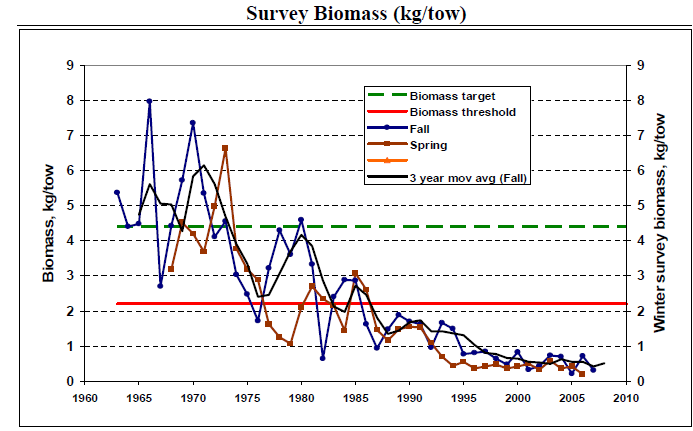

Due to both a directed fishery (skate wings are used for lobster trap bait, and also for food for a primarily-overseas market that includes Europe) and bycatch in bottom fisheries , Northwest Atlantic populations of these species have experienced serious declines in recent years. While some skate species have rebounded (for reasons that are not entirely clear), The thorny skate remains particularly threatened- the IUCN Red List considers the subpopulation off the Northeastern U.S. coast to be Critically Endangered. It is illegal for U.S. fishermen to keep thorny skates they catch (and has been since 2004), but they are commonly taken as bycatch in fisheries for the other skates and groundfish.

Yesterday, the National Marine Fisheries Service formally responded to the petition (thorny skate and other skates), and the news isn’t good for skates:

“After reviewing the information contained in the petition and information readily available in our files, we conclude that the petition fails to present substantial scientific or commercial information indicating that the petitioned action concerning barndoor, smooth and/or winter skate may be warranted…We find that the petitions do not present substantial scientific information indicating the petitioned actions may be warranted. Accordingly, we will not initiate a review of the status of thorny skate at this time.”

The National Marine Fisheries Service listed several reasons why they believe these skates should not be listed under the Endangered Species Act.

1) There is no evidence that the U.S. subpopulation of thorny skates is reproductively isolated from other subpopulations, which resulted in NMFS examining the species as a whole rather than the subpopulation that the IUCN Red List considers Critically Endangered. While the NMFS response acknowledges that “in the United States, surveys indicate that the population is at a historically low level”, it points out that “millions of thorny skate exist and their distribution ranges across vast areas on both sides of the North Atlantic”. In other words, a drastically reduced population isn’t that bad if there are still lots of animals remaining. The IUCN Red List made a similar point- their analysis considers the entire global population of thorny skates “Vulnerable” (again, they consider the subpopulation off the Notheastern U.S. to be “Critically Endangered”).

The IUCN Red List explains why they focus on different subpopulations of thorny skates:

“Tagging studies (Templeman 1984b for the northwest Atlantic, Grand Banks (Canada); Walker et al. (1997) for the northeast Atlantic) suggest that Thorny Skates are rather sedentary, as most (85%) were recaptured less than 90 km from the initial capture point (some after twenty years at liberty). This information along with differences in size of egg capsules (Templeman 1984a), and the great latitudinal differences in size (length) at sexual maturity among the areas sampled, led Templeman (1987) to conclude that no large-scale migrations of thorny skates occurred between the sampled areas.”

These points were cited by the petitions, and in response, NMFS replied:

“Contrary to the petitioner’s assertions, there is no evidence of reproductive isolation of any subpopulation of thorny skate across the North Atlantic Ocean. Connectivity across broad geographic regions reduces the overall risk of extinction, and buffers the potential impacts of fishing mortality on thorny skates.”

2) There is no evidence that bottom trawling negatively impacts the ecosystem in a way that affects the population of these skates. While many scientists consider bottom trawling to be among the most destructive fishing gears in use today, equivalent to cutting down a forest and killing everything in it in order to capture rabbits, NMFS needs specific data showing that the fishing gear will negatively impact the parts of the ecosystem that these skates need to survive. Specifically, there is no evidence that trawling in the region is “degrading benthic habitat structure and affecting the availability of the skate’s prey as well as the skate’s ability to avoid predators.” In contrast, the IUCN Red List recommends that in order to protect thorny skates, managers should “reduce bycatch by closing and/or reducing fishing effort (particularly otter trawling) in areas of high thorny skate concentration.”

3) I’ll present the last one verbatim: “While it is reasonable to predict that climate change will result in some changes to the habitat of thorny skate, sufficient information is not presented or otherwise available to indicate that climate change, or other natural or manmade factors, may be causing the species to be threatened or endangered. We conclude that the available information does not lead a reasonable person to conclude that thorny skates are threatened or endangered due to one or more of these factors at this time.”

The NMFS report noted that if more research becomes available ( including studies demonstrating reproductive isolation between subpopulations, negative effects of climate change on the populations of these animals, negative effects on skate habitat as a result of trawling gear, and the effects of disease on skate populations), they would reconsider listing these species under the Endangered Species Act. Masters Thesis, anyone?

In the meantime, no clear plan is in place for the New England Fishery Management Council to address the lack of thorny skate recovery relative to other species, and a proposed fishery increase could result in even higher thorny skate bycatch mortality.

Not everything is scientifically explained what will happen when you decide too late to help the Thorny Skate? Why are you in this position if deciding this fishes fate when you wont listen to advice offered. Surely you recognise the need for a wide gene pool ?

Interesting post. I’m still leery about attempts to list skates under the ESA, since I think for most species effective management may be all that is needed. The thorny skate is in trouble, but there is already evidence that the other three species are recovering due to decent fisheries management. The barndoor skate in particular is on its way back up (albeit slowly), and the winter skate is still common enough that frankly I’m surprised to see it on that list (though it could be a precautionary listing attempt i.e. spiny dogfish). I agree with Nick Dulvy’s talk at AES that size limits would probably be sufficient to help thornies recover. However, I have some comments about the three reasons given by NMFS for the rejection:

1 – Lack of isolation is a questionable justification. Other small elasmobranchs are pretty wide-ranged without much mixing between populations. Very rarely, spiny dogfish will make transoceanic migrations, but not at a level sufficient to compensate for population loss in other regions (our relatively healthy dogfish stock in the U.S. has yet to show any evidence of replenishing the population in Europe). Skates have much shorter migrations, so I don’t really buy this argument (though there is a lot of connectivity between U.S. and Canadian populations).

2 – Skates are pretty adaptable to both structured and unstructured bottoms, so I can see the point about trawling not necessarily destroying skate-specific habitat. Some of their prey (benthic inverts) would certainly benefit from a break from trawling, but again, skates are generalists and can likely switch to consuming other species. Also, skates fare better with bycatch survival than a lot of marine animals.

3 – The climate change argument is an interesting one. With most skate species (especially winter skates) being very adaptable, most other sea life would be much worse off by the time skates starting being significantly affected. Winter skates can be found in deep waters off of North Carolina even in the summer. Rising temperatures would drive coldwater species offshore and north, but in most scenarious they could probably still be found in most places they’re found now.

Apologies for the long comment. Just thought I’d toss my two cents in there.

My next question would then be, if these skate species have not been designated the required protection they need then what what work is being done to educate local fishermen. Politicians are often slow to react or the scientific evidence not communicated well to them. This is common and should not stop fisheries scientists from working with local fishermen.

No petition to sign to try to help?

Jan, I don’t understand your question… it seems like you think I’m the one who made this decision?

Nope. A public petition would not result in NMFS reconsidering their decision, only new research would.

It’s ironic that NMFS wants list every salmon run as Endangered based upon local minor genetic “isolation” that can be caused by founder effects and be of no real significance. In the case of salmon, the endangered label is use to obtain power over water and energy resources and benefits the NMFS’s budget and political power.

Protecting a skate against the clear cutting by bottom trawlers would shut down one of their regulatory clients and that would harm the NMFS, so there will never be enough information to act. With the low mobility of this species, finding genotype variation as a function of location highly probable. With enough markers or whole genome analysis, such “isolation” could easily be demonstrated.

However, in this case, no amount of genetic “isolation” that hasn’t created an obvious, measurable and significant phenotype difference would be considered adequate “isolation”. It is all bureaucratic politics and not science.

Without mandatory independent observer data on the by-catch, NMFS has no idea how much damage the bottom trawlers are doing. However, there is a ton of data from around the world showing that bottom trawling does massive damage.

Interesting. I think NMFS is going to proceed very cautiously on this one–by that I mean, shelving it for now. New England fisheries are complicated and riff with growing pains. What complicates it from a managers point of view is the sheer number of commercial and non-commercial species a trawler or gillnetter can encounter. That’s what happens when you have a large shelf–same as the North Sea and Nova Scotia–and ocean currents and diverse bottom types. But the multispecies fisheries has made managing New England fisheries a real challenge, even more so now that sector management is in place and you have choke species that can, if the sector quota is reached, shut fishing down in that sector. And the rarer the fish the smaller the quota, the more it is a choke species. Managers right now don’t want a large groundfish sector to be shut down because a handful of thorny skates were caught off Georges Bank.

It’s all too new. What I’m saying here is that NMFS wants to give the new management time to work and also give the fishermen and communities time to figure out how to survive. Skate can wait–or that is what I bet is being said behind closed doors. I bet it is the same with river herring. Ecosystem management simply isn’t here yet.