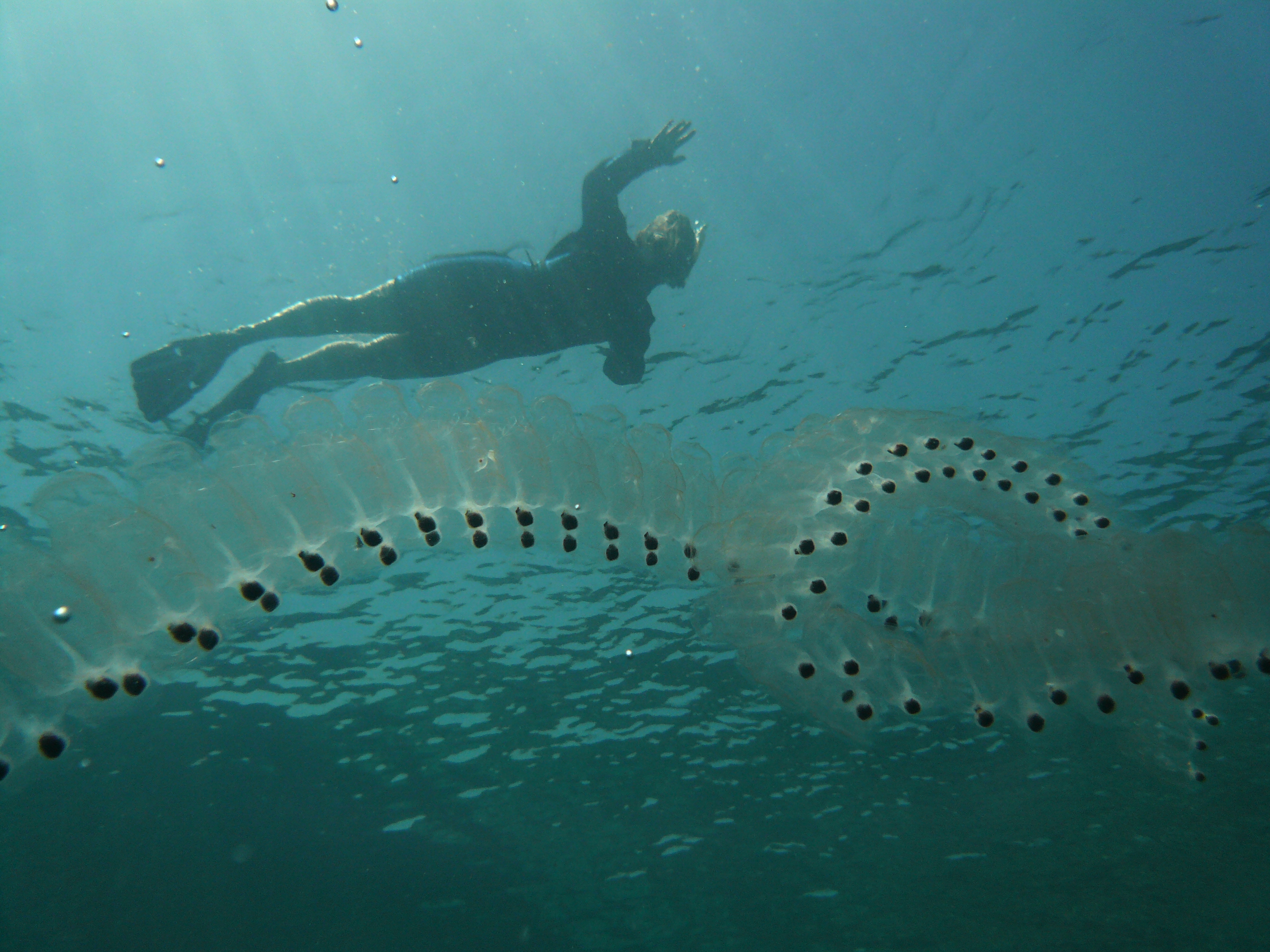

I’m a bit late to the party, but last week, several news outlets reported that the Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant was taken offline by “jellyfish-like creatures” that clogged several cooling intakes. While most sources were careful to point out that these were “jellyfish-like” organisms, some secondary sources truncated the description and announced that “Nuclear Power Plant Knocked Offline By Tiny Jellyfish, The Invasion Has Begun”. Unfortunately, these organisms are salps, not jellyfish, and you’d be more correct to describe them as human-like rather than jellyfish-like.

Salps are free-swimming pelagic tunicates, one of the most basal members of the chordate phylum. While they superficially resemble jellies to the untrained eye, they are far more derived, possessing three tissue layers (compared to the jelly’s two), a primitive, larval notochord, a perforated pharynx, and the rudimentary beginnings of a centralized nervous system. They form large, clonal colonies that are able to take advantage of plankton blooms by rapidly producing more clones to capitalize on an unpredicatable food source. Although I don’t have first hand reports, this is likely what happened in Diablo Canyon, as warm water discharges from nuclear power plants can trigger massive plankton blooms. Far from a “jellyfish invasion”, this was probably the natural response of a predator to increased food availability.

There’s been quite a few taxonomy fails in the news recently, from carcass monsters to frapachino beetles. Several years ago, Alex Wild of Myrmecos proposed the “Taxonomy Fail Index” a measure of how bad a species identification is “scaled by the amount of error in absolute time against the error of misidentifying a human with a chimp“. Describing a person as a bonobo would be a TFI of 1. Wild’s example of a possum misidentified as a cat pulls in a TFI of 24.6.

So what about misidentifying salps as jellyfish? TimeTree is a pretty good resource for calculating divergence time between species, and yields 891.8 million years for a representative salp genus and a representative cnidarian genus. Other sources confirm this estimate and put the divergence time at between 800 and 900 million years ago. At 891.8 MYA over the 6.4 MYA used to scale to a human/chimp identification, our jellyFAIL has a whopping TFI of 139.3!

So here’s my challenge to our readers: find me a mainstream media taxonomy fail in domain Eukaryota with a TFI higher than 139.3. The winner will receive a copy of “The NEW SCIENCE of SKIN and SCUBA DIVING” a 1960’s era SCUBA manual full of hilarious historical anecdotes and illustrations. Happy hunting!

LOL! I think I have a fail of 144 somewhere…will have to dig that up 😀

144? Unless someone thought a placozoan was a planarian you’d have to cross kingdoms for a taxfail like that.

thanks for helping me identify the critters i’ve been seeing washed up along the beach in morro bay (a few miles north of diablo) the last few days…

literally thousands of them. the ones i’ve seen range in size from about 1.5 to 2.5 inches and in their dead state on the sand look like a cyclopian worm/jelly.

the internal structure, except for its brownish round nucleus (its stomach and intestine apparently). fascinating!

144 is pretty epic.

If someone mistook a colonial tunicate for a loofah plant, you’d get a TaxFail of 361.4

Placozoan to planarian (which is the most extreme I can think of that could realistically be misidentified) would be 146.8. But of course, the challenge is to find a TaxFail in the press, not in my imagination.

Your claim that “you’d be more correct to describe them as human-like rather than jellyfish-like” deserves its own TFI score. TimeTree reports a 722.5Mya divergence between salpida and humans. So there were 169.3M years between the common ancestor of salps and jellyfish and 716.1M years between the common ancestor of salps and humans and the origin of humans. If we subtract those two figures, your “more correct” comparison neglects 546.8M years of diversification. That’s a TFI score of 85.

Nuke plant shuts down when water intake clogged by human-like sea creatures!

With a TFI of 112.9, for a salp/human TaxFail, salps are much more closely related to us than to jellyfish, which is precisely my point.

Nope. Those numbers show that salps are more closely related to us than jellyfish are related to us. When you say “salps are much more closely related to us than to jellyfish” you need a different form of analysis that treats salps as an intermediate. That’s what I did. Salps are 169.3M years divergent from jellyfish and 716.1M years divergent from humans. You are basically saying that 169 million years of change is greater than 716 million years of change. That’s silly.

Darn best I’ve seem is tunicates ID’d as sponges.

Actually, what you’ve got are the dates for the common ancestor of salps and humans. So yes, the most recent common ancestor of salps and humans are more closely related to jellyfish than humans (or salps), but modern salps are, well, modern. They didn’t stop evolving after they branched off from us. Salps are not an intermediate form, they are a modern derivative of an ancient common ancestor. Both humans and salps are equally as closely related to our most recent common ancestor.

Sticking with TimeTree, all modern bilaterians, including humans and salps, diverged from jellyfish 891.8 million years ago.

If you’ve got a mainstream media link, that would beat salp to jellyfish.

You are either conceding the point or dodging it, so I should probably just drop it, but you are the one who is putting salps in an intermediate position on a spectrum between jellyfish and humans and asserting, or at least you were asserting, that they are closer to humans. Of course, they are chronologically intermediate, and while it is tediously obvious that modern forms are modern, it remains useful and reasonable to speak of some modern forms and features as primitive and others as derived, as you did when describing salps as “one of the most basal members of the chordate phylum.”

I think you overstated your case when you asserted that it is “more correct” to describe salps as “human-like” than “jellyfish-like,” and I computed a TFI score for you. What is actually correct is that humans are more salp-like than jellyfish-like. Since evolution is undirected, such relationships are not necessarily symmetric.

I’m sorry, I guess I’m not being as clear as possible. I am not conceding nor dodging your point. Your assertion that “Salps are 169.3M years divergent from jellyfish” and that salps should be treated as intermediate between humans and jellyfish is wrong. Clearly and unambiguously, by any interpretation of our current understanding of phylogenetics and evolution, wrong.

Humans and jellyfish share a common ancestor 891.8 million years ago. Salps and jellyfish share a common ancestor 891.8 million years ago. Salps and humans share a common ancestor 722.5 million years ago. Salps and humans are absolutely, barring a radical change to our current understanding of the evolutionary history of animals, more closely related to each other than either is to jellyfish.

Salps are not “chronologically intermediate”. The common ancestor of salps and humans that diverged from the common ancestor of jellyfish is intermediate, and the branch that includes the clade which contains salps, but not humans, is a basal branch in the overall chordate clade, but terms like “basal” and “derived” are not statements of time, but rather refer to phylogenetic relationships.

Perhaps if you’re thinking purely in terms of morphology, then I can see where you would think salps are more jellyfish-like than human-like, they are superficially similar, but it is important to remember that the shared common ancestor of salps and humans was not a salp. Salps are highly derived tunicates. The common ancestor of salps and humans was also not a tunicate any more than it was a primate. And though jellyfish appear extremely primitive, and it’s possible that the shared common ancestor of salps, humans, and jellyfish, was superficially jelly-fish like, it may not have resembled anything like a modern cnidarian.

Jellyfish, salps, and humans are modern taxa. Through genetics, morphology, and fossil evidence we can glimpse the evolutionary history of these groups, but evolution doesn’t stop at the moment of divergence, and the relationship between modern taxa cannot be interpreted as if modern taxa that are basal to us are somehow less evolved.

In closing, salps are more human-like than jellyfish-like, humans are more salp-like than jellyfish-like. Jellyfish are equally salp-like and human-like.

You keep telling me things I already know. We agree that salps are not an intermediate form. “Intermediate form” is a nonsense concept, particularly when talking about creatures thousands and millions of evolutionary steps removed.

Likewise, your choice of “more closely related” as the definition of “like” explains quite a bit about our disagreement. That’s a very useful definition if you are talking about a few species within a genus, but not worth much talking about things whose common ancestor lies on the far side of the Cambrian. Certainly it is slightly less absurd to compare humans to salps than to jellyfish, and if that’s your point, huzzah!

The only use I have for the concept of “intermediate” is mathematical. When computing a TFI for the jellyfish-salp misidentification, you have only two endpointsand no intermediate. Throw in a third organism and you need to know which order to evaluate them in. As we know, first there was a planet with cnidarians on it, then there was a planet with cnidarians and salpids, and now there is a planet with cnidarians, salpids and humans. The origin of salpids is chronologically intermediate.

The three organisms in question are humans at 6.4Mya, the human-salp common ancestor at 722.5Mya and the salp-jellyfish common ancestor at 891.8Mya. As you can see, 722.5 is intermediate between 6.4 and 891.8. That is the definition of the word “intermediate” I am employing.

Your contention that ancestral cnidarians “may not have resembled anything like a modern cnidarian” substitutes bewilderment for uncertainty, but it is a testable hypothesis. We have fossil cnidarians and salpids. They are ancient, yet they are still recognizable as cnidarians and salpids. As you’ve already explained, the cnidarians have radial symmetry, rudimentary nerve structure, etc. The salpids have bilateral symmetry, a mesoderm, notochord, etc. Pretending ancestral forms might be unimaginably, unrecognizably different from their modern representatives is a sad dodge, though common among biologists who like to wish away the historical dimension to phylogenetic studies.

Phylogenetic assertions like “basal” and “derived” most definitely have a temporal dimension. That is the whole point of phylogenetics, to understand and discover evolutionary progression. In this particular progression, the gelatinous sea creature with a simple notochord is a lot more like the gelatinous creature with radial symmetry that preceded it than the highly derived mammal that arose hundreds of millions of years later, following the evolution of terrestrial life. If you do the math right, that is what the numbers show.

Ok, so we’re basically in agreement on everything except for the mathematics and your interpretation of the terms “basal” and “derived”. Those terms can have a temporal component, but they speak primarily to relationships among organisms. Hence, salps can simultaneously be basal chordates and extremely derived metazoans without compromising their position on the tree of life.

In a world that contains only humans, salps, and jellies, let’s look at a hypothetical tree (the one above will do): Here we have A, the shared common ancestor of jellies, salps, and humans; B, the shared common ancestor of salps and humans; C modern jellies; D modern humans; and E modern salps. In this example, both humans and salps are derive from jellies, and jellies are basal to humans and salps, but, because there are no other taxa, humans are neither derived, nor basal to salps, nor are salps either derived or basal to humans. A diverged into B and C 891 million years ago, B diverged in D and E 722 million years ago. In this example, it is correct to say that B is an intermediate form between D and E, and even mathematically intermediate between A and E, but that is not equivalent to E being intermediate, mathematical or otherwise.

If I understand your argument correctly, you’re saying that, because B is chronologically closer to A, and B probably looked more like E than like D, that E is more like A than like D. I would say that is false. B is the shared common ancestor of D and E, it is equally true to say that B is an ancient E as it is to say B is an ancient D. Both D and E diverged from B at the same time. The TFI the you’re calculating is the TFI you would get if you accidentally identified either D or E as B. Further, C diverged from both D and E at the same time (since both D and E were the same lineage at that point on the tree).

I also posit that you’re making an arbitrary distinction when you say “the gelatinous sea creature with a simple notochord is a lot more like the gelatinous creature with radial symmetry that preceded it than the highly derived mammal that arose hundreds of millions of years later, following the evolution of terrestrial life.” I would argue that possessing a notochord, three tissue layers, bilateral symmetry, and a host of other chordate characteristics massively trumps being gelatinous as defining characteristics, which make salps much more like highly derived mammals than relatively basal jellies. But of course, we’re choosing to draw morphological lines in the sand, which is why I stick with phylogentic relatedness as a measure of the “likeness” of two organisms.

E is more like D than C. E and D are equally like B. C is equally like D and E, but most like A. B is more like A than C, D, or E.

It is also not a “sad dodge” to argue that a common ancestor is not necessarily morphologically similar to basal descendants. You’re essentially ignoring the evolutionary history of basal groups in a taxa after they diverge. Whether or not they were radially symmetric, two-tissue layer having, gelatinous organisms, modern jellyfish are as evolutionarily distant from A as we are. You’re also ignoring the dozens of more basal phyla that emerge between cnidarians and chordates, that look nothing like either salps of jellyfish.

And of course, while we’re on the subject of common ancestry, salps (and other Thaliaceans) are not basal among tunicates, but rather fairly derived.

Now that we’ve wasted so much time arguing about things on which we do not disagree, perhaps we can step back and see whether there actually is disagreement. It was your statement about it being “more correct” to refer to salps as “human-like” than to call them jellyfish. We agree that phylogenetic relatedness is the desired metric.

I contend that the proper mathematical analysis of that statement is a comparison of the distance AB with the distance BD. AB gives us a measure of relatedness between the cnidarian clade and the salp clade (or Urochordate or whatever the most accurate label might be). That distance is 891-722=169 million years. BD is the distance between where Urochordates branch off and the human branch. That distance is 722-6=716 million years. Because 716>169, salps are phylogenetically closer to jellyfish than they are to humans.

I pretty well demonstrated why this is not the case in my comment above. B does not just include salps, it is also the common ancestor of humans. AB is not the correct measurement of the relatedness of salps to jellyfish, it’s a measure of the relatedness between jellyfish and the most recent common ancestor of salps and humans. All modern chodates, of any stripe, are more closely related to each other than to anything that is not a chordate.

I don’t think discussing evolutionary theory or phylogenics is ever a waste of time, but we have reached a wall, one that hinges on a misinterpretation of phylogenetic information. B and all of it’s descendants, including D and E, form a clade that does not include A or C. Any individuals within a specified clade are by definition more closely related to each other than any individual outside of that clade. Please check out this resource from Berkeley for a short primer on how to read phylogenetic trees: http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evolibrary/article/phylogenetics_02

This is not so much a discussion of evolution or phylogenetics as it is a discussion of what you think I don’t know. Let’s focus on you instead by mapping your statement onto the tree. You are comparing EB with EA and using the fact that EA is longer than EB as proof that your statement is valid.

The problem, of course, is that EA is always longer than EB, so your metric actually tells us nothing except that you’ve rigged the game. You are asserting that any given lineage is always more like its derived relatives than its ancestral relatives. That is a remarkably rigid perspective, and it has yielded an uninteresting definition of what it means for an organism to be “like” another organism.

There’s really nothing else to add. Of course EA will always be longer than EB, phylogenetic trees show relationships, and modern salps will always be more closely related to humans than to jellyfish. It’s not a rigged game, it’s how we represent evolutionary history. Please read the reference I provided to the Berkeley site. I’m sorry your uninterested, but that’s not really my problem.

Again, the issue is not my interests nor ignorance. I am very interested in this subject, enough so to keep talking despite your rudeness. The issue is that your definition of “like” is sterile, and your metric always yields the same answer. A metric for “likeness” that sometimes says “this lineage is more like what existed before it than what came after it” and sometimes says “this lineage is more like what came after than before” would be an interesting metric.

Your metric says that at the moment any lineage diverges from “the bigger tree of life” it will always be more like lineages that do not yet exist than it is like its ancestors. You are saying that salps are more like some hypothetical chordate that will not evolve for another 500 million years than they are like jellyfish. A metric that does not even need an actual data point is simply uninteresting.

I’m too interested in evolutionary history to pretend that changes after some bifurcation always matter less than prior changes. Comparing the evolutionary novelties that arose between the cnidarian branch and the salp branch with those that arose between salps and hominids is complicated and messy, but interesting. Debating whether the innovations that set the stage for chordate evolution are more or less significant than the innovations that occurred on that stage would be interesting. But there is always the option of disregarding the particulars and collapsing everything interesting into a simplistic, tidy metric.

Yeesh, talk about moving goalposts. We agreed several comments ago that the only metric of “like-ness” that wasn’t arbitrary was phylogenetic relatedness. Now, I have no idea what you’re arguing for: a metric based on superficial similarity? One where we assume that shared common ancestors are appropriate stand-ins for modern decendents?

The most recent common ancestor of salps and humans is not a salp. B is not a salp. AB does not reflect the evolutionary relationship of jellyfish to salps. There is no reading of our current understanding of the tree of life that has modern salps more closely related to jellyfish than to humans. The changes that happened between jellyfish and bilatarians are huge: bilateral symmetry, the development of three tissue layers. They’re among the deepest and earliest developments in animal evolution.

“My metric” is phylogentics, and I’m not talking about the “moment any lineage diverges”, I’m talking about organism that exist now, and how they are related to other organisms that exist now, and how that all fits into the history of animal evolution. I’ve already shown that not only is the common ancestor of salps and humans not a salp, but that salps are a relatively modern group of tunicates that are derived relative to other urochordates.

I’m sorry if you think I’ve come off as rude (though I’m not the one who’s been dismissing arguments as “tediously obvious” or a “sad dodge”), but I’m trying to figure out where you interpretation is coming from. It’s clear now that you need to learn how to read phylogentic trees. Did you look at the reference I provided? The Berkeley evolution group is a great resource.

Also, since when is a metric that always yields the same answer a bad thing? Would you rather we have unreliable metrics that fluctuate with the whim of the measurer?

This post gets at the heart of our different interpretations. You insist that you are only talking about modern organisms, but you are using data that brings all sorts of historical and representational baggage with it. You want to be precise, and you don’t want to talk about ancient organisms because it is impossible to be precise about those.

I see the question more abstractly. With humans we are talking about a single species and one that is very recent, but with salps and jellyfish we are talking about clades or groups that have been around for many geological ages. I know that modern species are not appropriate stand-ins for their ancestors, but I’m already thinking of these groups in an abstract sense that encompasses their full diversity, so including some soft notion of what a common ancestor may have been like doesn’t bother me. So, yes, I’m looking for a metric that includes at least an approximate notion of the common ancestors in question.

According to the Berkeley page, the branch lengths in a phylogeny “indicate amount of character change.” They also say that clades include their ancestor, so your insistence that B is not a salp is a semantic, not a mathematical objection. I am not a master of nomenclature, and I’ve tried to point out that I may not have the right label for a given tree topology. In any case, we are concerned with three topologies: a tiny clade that includes only D, a much larger clade that includes B,D and E, and a giant clade that includes the whole tree. To me, the question of likeness inherently involves physical characteristics of the organisms or groups, so I want a metric that involves character change, thus my choice to compare length AB with length BD, consistent with the two Berkeley concepts I have mentioned.

Since salps are a derived tunicate, we may need a slightly more complex tree that splits at E so we have a clade that is truly just salps and not all tunicates or Urochordates. In that case, we’d want to compare length ABE with length DBE.

See, the problem with that interpretation is that the common ancestor B could be just as accurately described as a salp or a human, so deciding that that is a semantic or mathematical cut-off for salps is incorrect. We’re far afield, here, and while I think you’re dead wrong, I don’t disagree with the notion that examining evolutionary history is a fairly abstract process, but that’s not what we’re talking about, and you’re actually oversimplifying evolutionary processes by inferring a hierarchy in which basal branches are somehow less-evolved and therefore more closely related to their common ancestor than more derived forms.

I presented a taxonomic fail, in which a modern organism was misidentified as another modern organism. I posited that this taxonomic fail was so bad that despite some trivial morphological similarities, they would have been more correct to misidentify it as a third modern organism (one that is closely related, but so morphologically different that anyone could see that they were not the same). You then argued that modern organism E is more closely related to modern organism C than to modern organism D because common ancestor B is more closely related to common ancestor A. This is wrong.