3D printers are awesome.

That sentiment really shouldn’t surprise anyone who follows this blog. From oceanographic equipment, to farm tools, to just things around the house, over the last year I’ve made 3D printing a standard part of my toolbox.

A conversation last week on Twitter got me thinking again about 3D printers, safety, and disposability. On one hand, by allowing us to fabricate intricate custom parts at home, 3D printers can help us reduce the amount of waste produced and allow us to extend the life of otherwise disposable items. On the other hand, 3D printers produce their own plastic waste, particularly if, like me, you develop a lot of new projects from scratch.

Meanwhile, while many household 3D printers can be found sitting in an office, classroom, or other enclosed space, these machines are not harmless. The science on volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and other ultrafine particle emissions from 3D printers is still in its infancy, but early studies suggest that 3D printing releases VOCs at rates equivalent to that of a scented candle all the way up to a cigarette. In other words, probably not too bad in the short term, but chronic exposure can become a problem.

A selection of the current state of research:

- Emissions of Ultrafine Particles and Volatile Organic Compounds from Commercially Available Desktop Three-Dimensional Printers with Multiple Filaments

- Emissions of Nanoparticles and Gaseous Material from 3D Printer Operation

- Ultrafine particle emissions from desktop 3D printers

In addition, some 3D printed parts may be toxic to aquatic animals, though the sole study is very preliminary.

So what is an environmentally and health conscious maker to do? For starters, print in a well-ventilated area. And I mean properly ventilated, like a workshop with an air handler, if you can. Don’t run your printers in a living space with still are. A general rule of thumb is that a properly ventilated workspace should move three times as much air as the volume of the room per hour. Opening a few windows on a calm day isn’t going to cut it.

As it happens, your home might actually have a high-capacity fume hood. Over the stove.

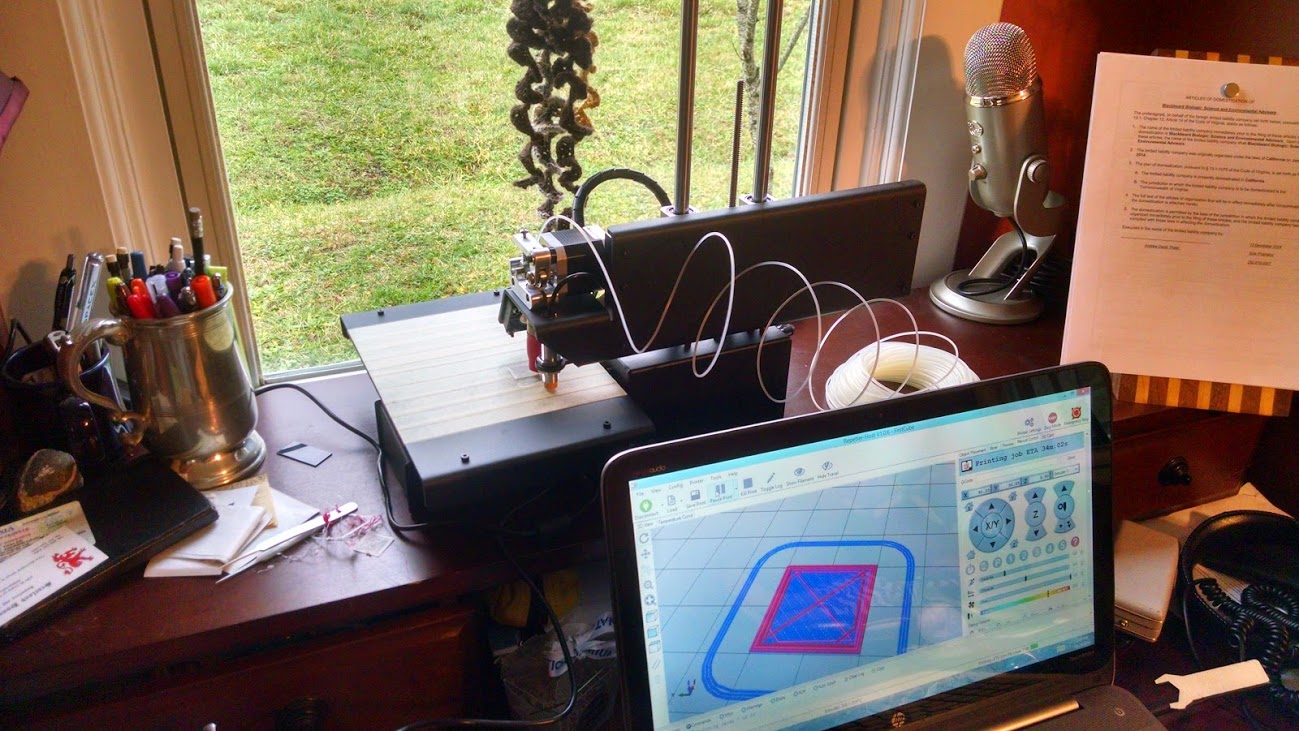

As I’ve refined my own protocols, I’ve taken to running all my prints either in my detached workshop (for long prints) or under the kitchen hood (for rapid prototyping). This keeps the printer away from living spaces, under a ventilator, and still accessible.

But what about the materials?

Home 3D printers can print in a variety of materials, from the mundane to the exotic, but by far the most common is the humble polylactic acid, of PLA, better known to many as corn plastic. PLA is a bioplastic made from plant material, corn or sugarcane primarily. It is marketed as biodegradable and compostable (in an industrial composter).

Look, hydrocarbons are hydrocarbons, regardless of their source of origin, and while it’s arguably better for the environment that PLA comes from a renewable resource, that doesn’t necessarily speak to the post-discard effects of PLA.

In terms of toxicity, PLA is Generally Recognizes As Safe (which is an actual food safety category) and, when it breaks down in controlled settings, produces ethanol, acetic acid, and lactic acid, and allegedly ends its life as carbon dioxide and water.

So you’re probably not going to destroy the planet with a few PLA scraps, and if you have a composter that can hit 140°C for ten consecutive days, you could ever shred and compost your old prints, which, I guess, would technically be 3D printed soil. You should check with the manufacturers of each filament to ensure that the dyes used to color the filament are also GRAS.

You could also build a filament extruder and recycle your old prints into new filament, but then you’re back to the trade-off between volatile organics and plastic decomposition.

Other plastics, like ABS, NinjaFlex, Nylon, resins, and exotics are not necessarily as safe, and users need to explore the potential impacts of printing with the plastics on both their health and the health of the planet. ABS, for example, is not Generally Recognizes As Safe. My recommendation: Since PLA is generally regarded to be the least harmful 3D printer plastic, prototyping should always be done using PLA and other plastics reserved for the final print.

Of course, the most important thing you can do is keep up with the latest science and follow the recommended best practices.

And please, let’s keep 3D printed ABS parts out of the ocean.

Hey Team Ocean! Southern Fried Science is entirely supported by contributions from our readers. Head over to Patreon to help keep our servers running an fund new and novel ocean outreach projects, like the BeagleBox 2. Even a dollar or two a month will go a long way towards keeping our website online and producing the high-quality marine science and conservation content you love.