In which I attempt to answer an interesting question I received during a public talk.

Much of the focus of my career in shark research, policy, and communications has been influenced by my time doing public science engagement on social media. I’ve attended dozens of scientific conferences and conservation policy meetings, I’ve spent thousands of hours talking to the non-expert ocean enthusiast public, and I noticed something important: both of these groups are talking about marine biology and conservation, but they’re talking about these topics very, very differently.

Troublingly, many of the ways that the non-expert ocean enthusiast public discusses these issues are factually wrong. And while we should be clear that science is not the only way of understanding the world, policy that is based on evidence and reality is far more likely to be effective than policy based on extremist lies.

This divide was recently captured nicely by an audience question at one of my public talks. After I had throughly explained that the shark fin trade is not the biggest or only threat to sharks (and hasn’t been in a long time,) and that making fisheries for sharks more sustainable is not only possible but endorsed over trying to ban all shark fishing by the vast majority of scientific and conservation experts, an audience member wearing a shark conservation t-shirt asked a great question. I wish I had written down his exact wording, but I’ll paraphase below:

“If the shark meat trade is such a big threat, if sustainable fisheries have so much evidence that they work and so many experts supporting them, why have I, a person who cares about the ocean and follows ocean conservation news, never heard of this threat and never heard of this solution?” I’ve been thinking about this question for months, and I’d like to try to answer it here.

A sarcastic (but perhaps not especially helpful) answer is that if you don’t have formal technical training or on-the-ground experience in these topics, there are probably a lot of true and important things that you havent heard of. But there’s a lot more to it than that. The real answer is complicated, nuanced, multifaceted, and important.

Part of the answer is that a lot of the people with the loudest voices about ocean conservation social media are not trained credentialed or experienced environmental advocates, they’re just people with loud voices who don’t feel compelled to learn anything about the topics that they’re screaming about before they start screaming. Social media algorithms promote extremism because it generates engagement (including from experts saying “hey that’s not true,”) and there are therefore perverse incentives to say nonsensical or even harmful things to break through the noise, even in cases where the people making those statements know actual facts about the real situation on the ground. And far too many online enviromental extremists don’t have any actual experience with any kind of conservation, which means they sincerely don’t even know that what they’re saying is wrong and harmful. The loudest voices are people who care about being heard more than they care about the accuracy of what they say.

Part of the answer is that a lot of the people who do know the complex technical details of evidence-based environmental advocacy aren’t spending much time talking to the public, because they’re busy working behind the scenes to make real change. And when these experts do try to speak to the public, they find their important voices drowned out by those extremists who are shouting unehlpful nonsense, so they get frustrated and give up.

This important divide- people with the biggest audience don’t share helpful things because they don’t know what’s really going on, people who know what’s really going on don’t engage with the public because they get shouted over- has shaped a great deal of my public science engagement strategy. I’ve worked to train experts in how to use social media tools for public science engagement, and I’ve built up an audience so I can help the experts (who don’t have time to build an audience themsleves) share important information with a wider audience. Those who have attended my professional development workshops know that the vast majority of what I share on my social media accounts is not my own work, but that of my colleagues, often with some translation or explanation from me attached to it.

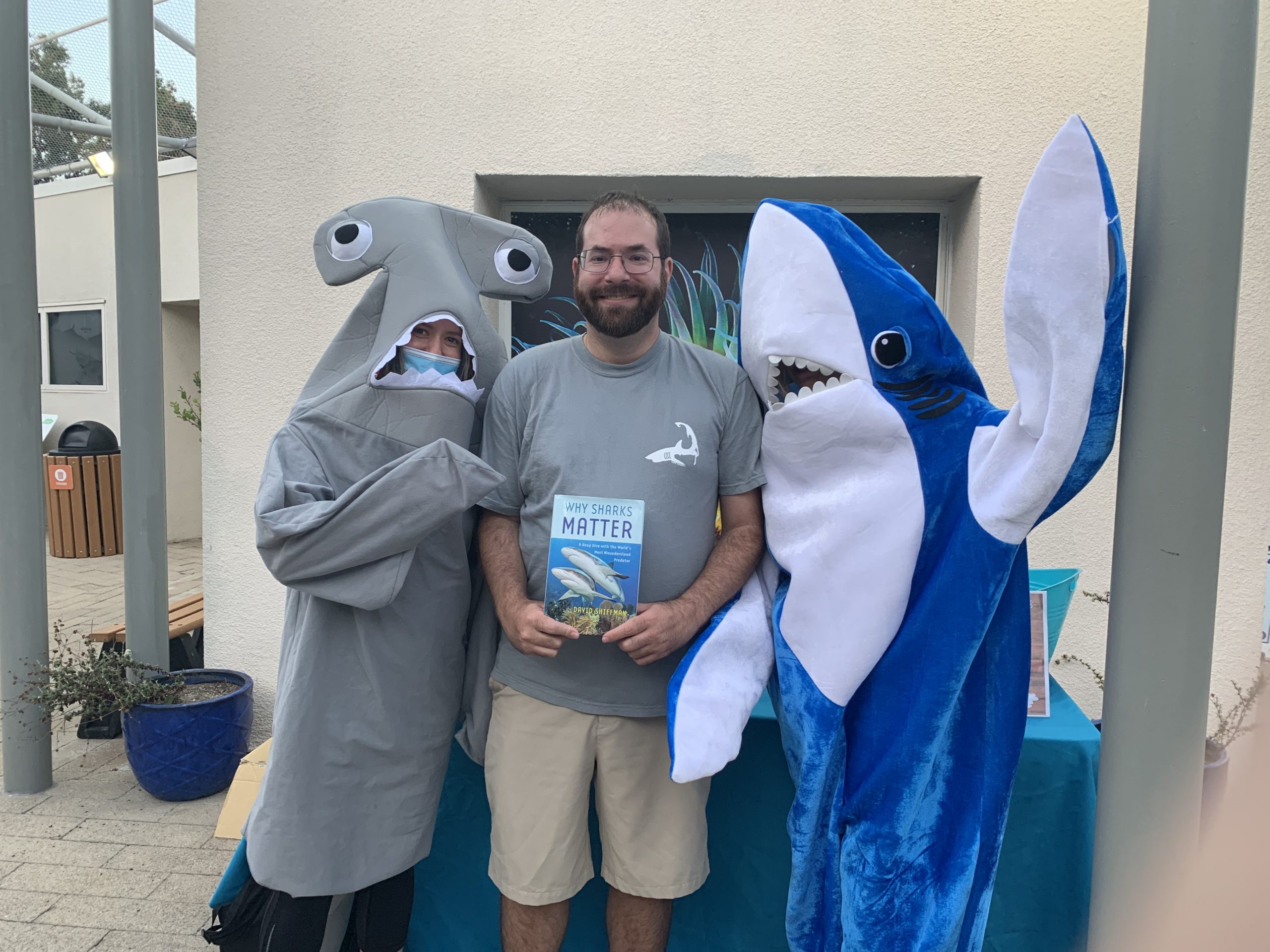

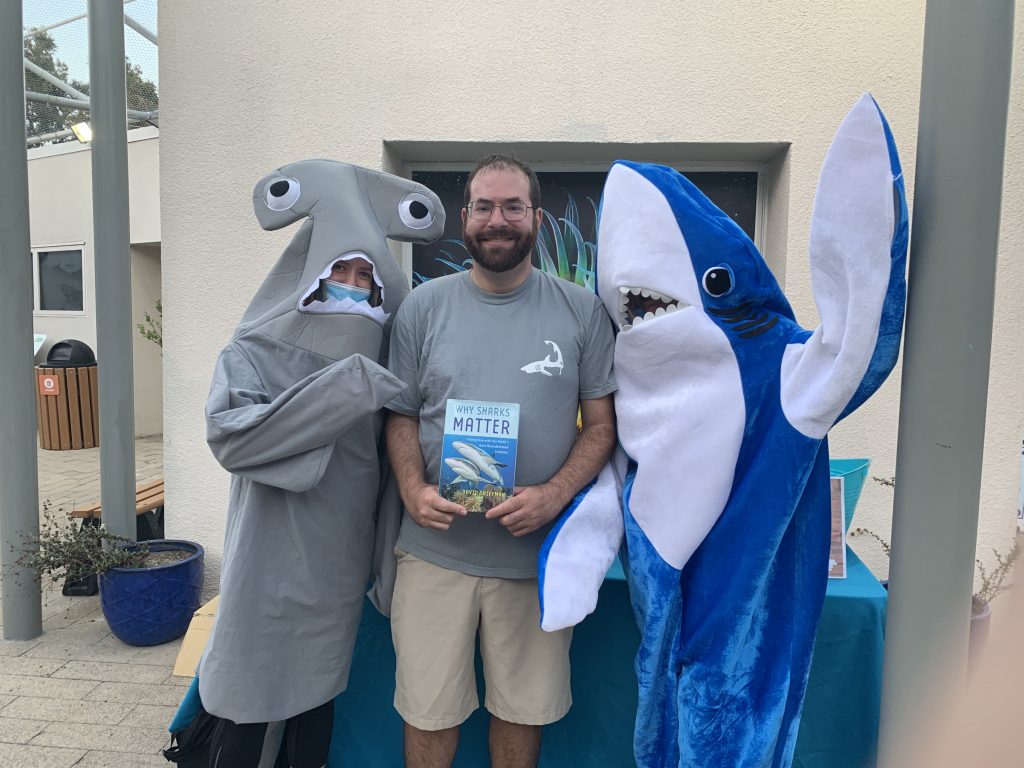

This is also a major reason why I wrote “Why Sharks Matter.” There are lots of shark books, including books that are highly technical and meant for experts and books that are meant for the interested public. The books about shark conservation that are accessible to the public are often full of oversimplifcations or outright falsehoods, while those that contain important facts and tips are too technical to be widely accessible. By writing a book that is accessible to the public and factually accurate and thorough, I’ve worked to bridge the divide.

There’s no doubt that passionate members of the public play vital roles in policy change- after all, scientists and conservation advocates aren’t the ones making any actual decisions. But I might respectfully suggest that if you’ve never heard of something that’s widely acknowledged by experts as the biggest threat, and if you’ve never heard of a solution endorsed by 78-90% of experts, that you should carefully examine where you are getting your information from. And I might respectfully suggest that passion directed towards evidence-based data-driven policy solutions to actual threats are likely to be more helpful to the causes that people claim to care about than only listening to the loudest voices who spend their time shouting extremist lies.