In a region once thought to be so ecologically uninteresting that it was viewed as a useful testbed for deep-sea mining equipment, NOAA researchers have detected what could be the world’s largest cold water coral reef. “For years we thought much of the Blake Plateau was sparsely inhabited, soft sediment, but after more than 10 years of systematic mapping and exploration, we have revealed one of the largest deep-sea coral reef habitats found to date anywhere in the world,” said Kasey Cantwell of NOAA Ocean Exploration, in a quote provided by NOAA.

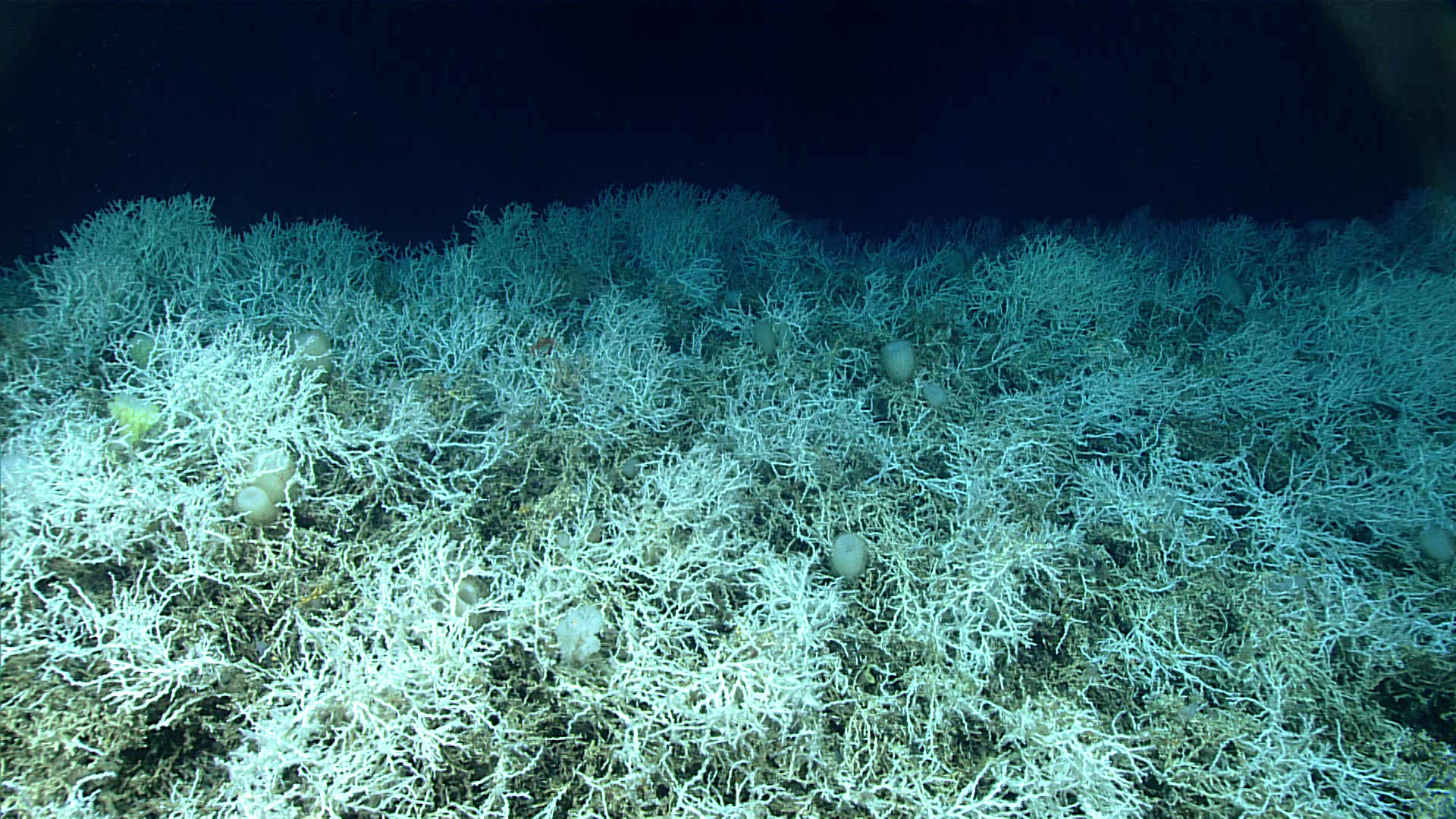

Cold water stony corals, like their tropical cousins, grow calcareous skeletons which not only protect the coral polyp inside, but create massive, topological complex structures that form the foundation of an entire ecosystem. Unlike their tropical cousins, cold water corals live too deep to benefit from sunlight. While tropical corals form symbiotic relationships with photosynthetic microbes, cold water corals have to feed themselves. Rather than basking in the suns rays, they filter feed, capturing food from the surrounding seawater.

One of the most consistent features of the deep sea is its stability. Most deep sea ecosystems enjoy an existence of relatively little disturbance, allowing them to persist, unmolested, for millennia. Cold water coral reefs are no exception. These reefs are long-lived and slow growing. That stability not only gives cold water corals the time and space to grown truly massive (in some cases cold water coral reefs alter the surface currents and induce nutrient downwelling), but also makes them incredibly vulnerable to disturbance.

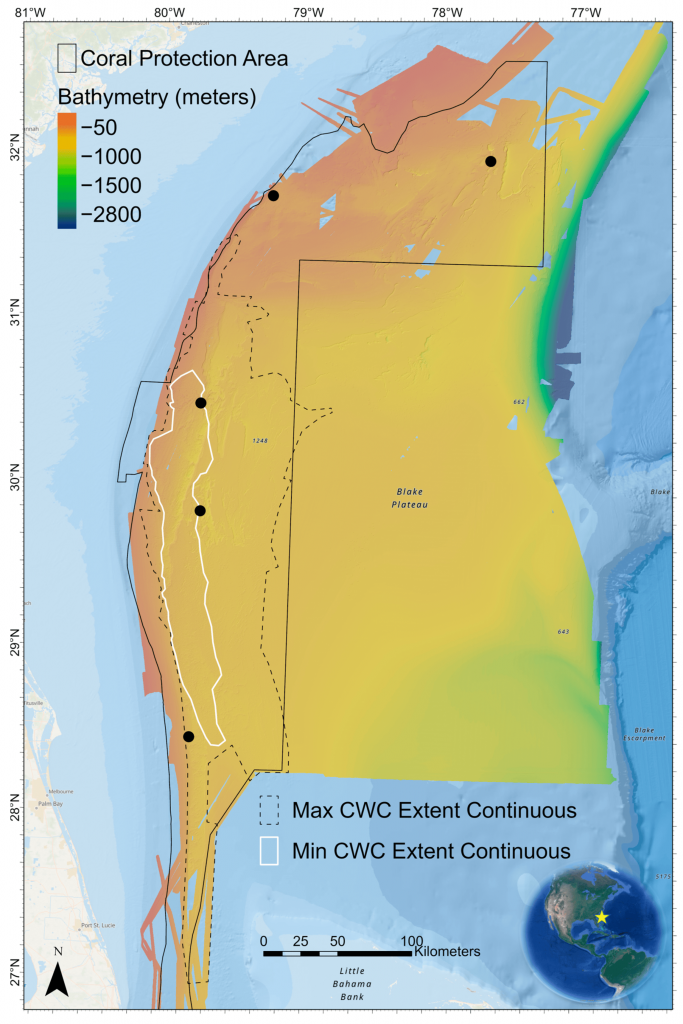

The Blake Plateau is a massive, flat feature with steep walls that lies offshore of the southeast United States, from Florida to North Carolina. The reef extends from Florida to South Carolina along 310 miles of the plateau and reaching a width of 68 miles. This 6.4 million acre ecosystem is larger than all but two of America’s national parks, and dwarfs Denali Nation Park and Reserve by over a million acres. The cold water coral reefs, comprised of Desmophyllum pertusum corals, may be among the largest contiguous ecosystems in the continental US.

(As an aside, I am annoyed that Lophelia got renamed. Not for any scientific reason, but because “Lophelia reef” sounds much more evocative than “Desmophyllum reef”. Lophelia, you’re breaking my heart.)

We’ve had an inkling that there were extensive deep water reefs off the Atlantic coast for over a decade, prompting the South Atlantic Fisheries Management Council to designate a Habitat Area of Particular Concern during the Obama Administration. This designation banned the use of bottom-gear by commercial fishermen. NOAA also kicked off a multi-year research effort to further quantify the extent of cold water coral reefs, of which this study is one of the major outcomes.

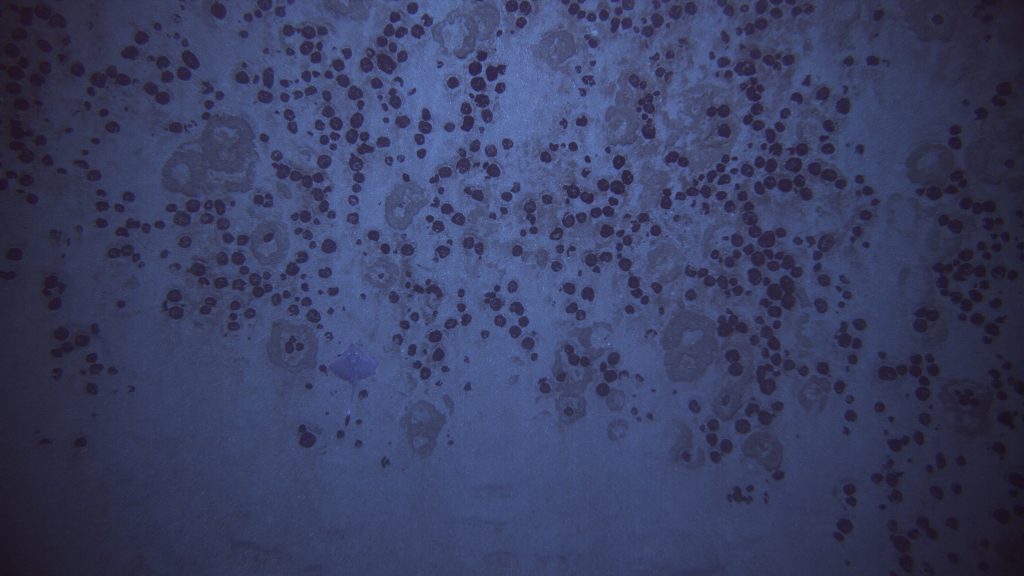

In 1970, a company called DeepSea Venture attempted the first experimental deep-sea mining test in modern history. Dragging a mining tool combined with a pumping system across the seafloor, they recovered polymetallic nodules. That test occurred on the Blake Plateau, within 100 kilometers of the densest portion of the cold-water coral reef and falling just south of the upper span of the designated Habitat Area of Particular Concern. Recent revisits to the test area have revealed an ecosystem that, 50 years later, has not recovered.

That that first experimental mining test landed so close to a massive ecosystem that wouldn’t be discovered for another 40 years is only surprising if you think of the deep ocean as a desolate waste defined by vast and empty fields of endless mud. The deep ocean is crawling, swimming, and pulsing with life, most of which has never been and will never be observed or described by science.

As countries gather this summer to debate the rules governing deep-sea mining in the high seas, and Norway has chosen to venture into mining seabed resources in its own waters, this is an important reminder that science knows precious little about life on the deep seafloor. One of the largest coral reefs in the world, spanning an area larger than four imperial Delawares, exists off the coast of the country with the greatest capacity for deep sea research and the longest history of deep-ocean exploration, and we’ve only just found out about it. How many other deep-sea ecosystems have we lost in the last two centuries without ever even knowing that they existed?

“This discovery highlights the importance of exploring our deepwater backyard and the power of interagency collaboration and public-private partnerships.” said Cantwell, in a quote provided by NOAA.

The paper Mapping and Geomorphic Characterization of the Vast Cold-Water Coral Mounds of the Blake Plateau is available open-access from the journal Geomatics.

Southern Fried Science is free and ad-free. Southern Fried Science and the OpenCTD project are supported by funding from our Patreon Subscribers. If you value these resources, please consider contributing a few dollars to help keep the servers running and the coffee flowing. We have stickers.

Featured image: Dense thickets of the reef-building coral Desmophyllum pertusum (previously called Lophelia pertusa) make up most of the deep-sea coral reef habitat found on the Blake Plateau in the Atlantic Ocean. The white coloring is healthy – deep-sea corals don’t rely on symbiotic algae, so they can’t bleach. Images of these corals were taken during a 2019 expedition dive off the coast of Florida. Image courtesy of NOAA Ocean Exploration, Windows to the Deep 2019

What’s the size of an “imperial Delaware”? 20% larger than cm American Delaware?