Giant deep-sea tube worms. When the RV Knorr arrived above Galapagos Rift in 1977, a team of geologists, geochemists, and geophysicist, including Robert Ballard who would go on to locate the wreck of the Titanic among other ocean-shaping discoveries) was prepared to witness something never before seen: a geyser of superheated, chemical rich water erupting from the seafloor at extreme depth and pressure. A deep-sea hydrothermal vent.

They were not prepared to find life, especially life that would fundamentally alter our view of what it means to be a living organism on Earth. When Alvin touched down on the site that would be soon named Garden of Eden, it found an oasis in the deep ocean–an ecosystem built by towering, bright red tube worms, who flower-like plumes wafted through the hydrothermal fluid. The discovery of these incredible ecosystems was so unexpected that Ballard, decades later, would write that those first specimens were preserved in vodka from the scientists’ personal stash.

Deep-sea tube worms, Riftia pachyptila, are pretty wild. Evolved to live in the dynamic and dangerous environment surrounding a hydrothermal vent they grow quickly and propagate widely. Lacking a digestive system and completely dependent on the chemoautotrophic microbes that live within specialized organs for sustenance, they can only survive near these vents. But in the presence of a chemical-rich hydrothermal vent, they don’t just survive, they thrive.

Tube worms aren’t the only organisms that thrive around hydrothermal vents. Shrimp, mussels, crabs, squat lobsters, barnacles, octopuses, and even fish call the halo of productivity around a hydrothermal vent home. And then there are the microbes. Bacteria and archaea adapted to exploit the chemical furnace of a hydrothermal vent are found in cracks and crevices, guts and gills, rock and mud, and even within the vent chimney itself. A growing body of work exposing the deep biosphere reveals that microbes can dwell deep beneath the seafloor, living off the heat and chemical energy of the hydrothermal system.

So here’s a question: If microbes can survive in the deep places, in cracks and crevices beneath the seafloor, and animals like the giant tube worm derive all of their energy from the vent fluid, mediated by some of the same microbes, require no sunlight, don’t need to be out in the open ocean to hunt, why shouldn’t we expect find tube worms in the deep places, too?

As it turns out, they do.

In Animal life in the shallow subseafloor crust at deep-sea hydrothermal vents, published this week in Nature Communications, Bright and friends overturned slabs around hydrothermal vents in the East Pacific to reveal crevices beneath the seafloor. And in those crevices, they found tube worms.

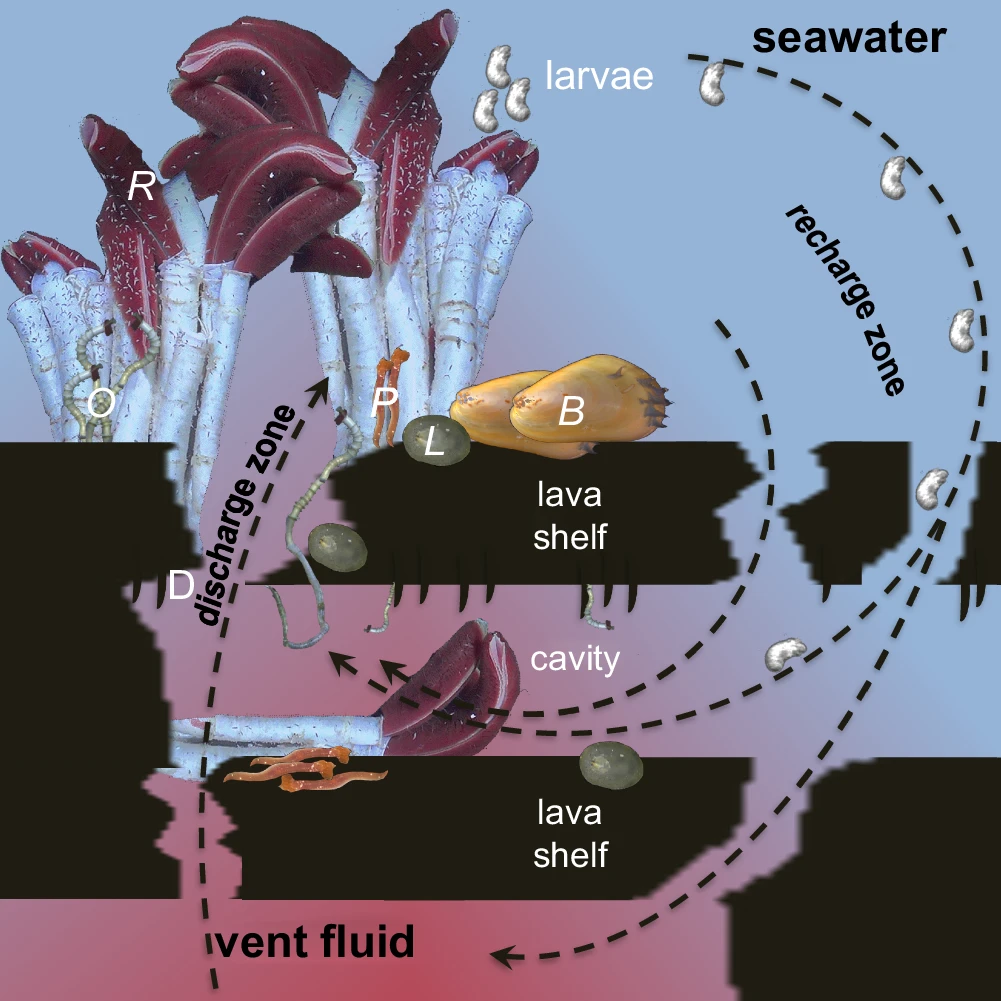

When giant deep-sea tube worm spawn, they broadcast their larvae into the water column. Some of those larvae become entrained in the the currents surrounding the vent and are carried carried down into the stock works. Those lucky enough to land within cavities (rather than boiled alive by the increasingly hot vent fluid) can settle out and grow just like any other tubeworm, exposed to a chemically-enrich plume of delicious hydrothermal fluid and protected from external threats on the seafloor. It seems like a pretty good deal.

What this all means is that hydrothermal vent ecosystems can extend far beyond what is visible, not just horizontally across the seafloor, but vertically down into the subseafloor biosphere. The deep biosphere, assumed to be the exclusive domain of microbes, is even more complex that previously known. And beyond that, I think there is a profound beauty in the fact that we can still fundamentally alter our understanding of what it means to be a living thing on this planet by flipping over a few rocks.

The ocean is big and weird and we are just getting started.

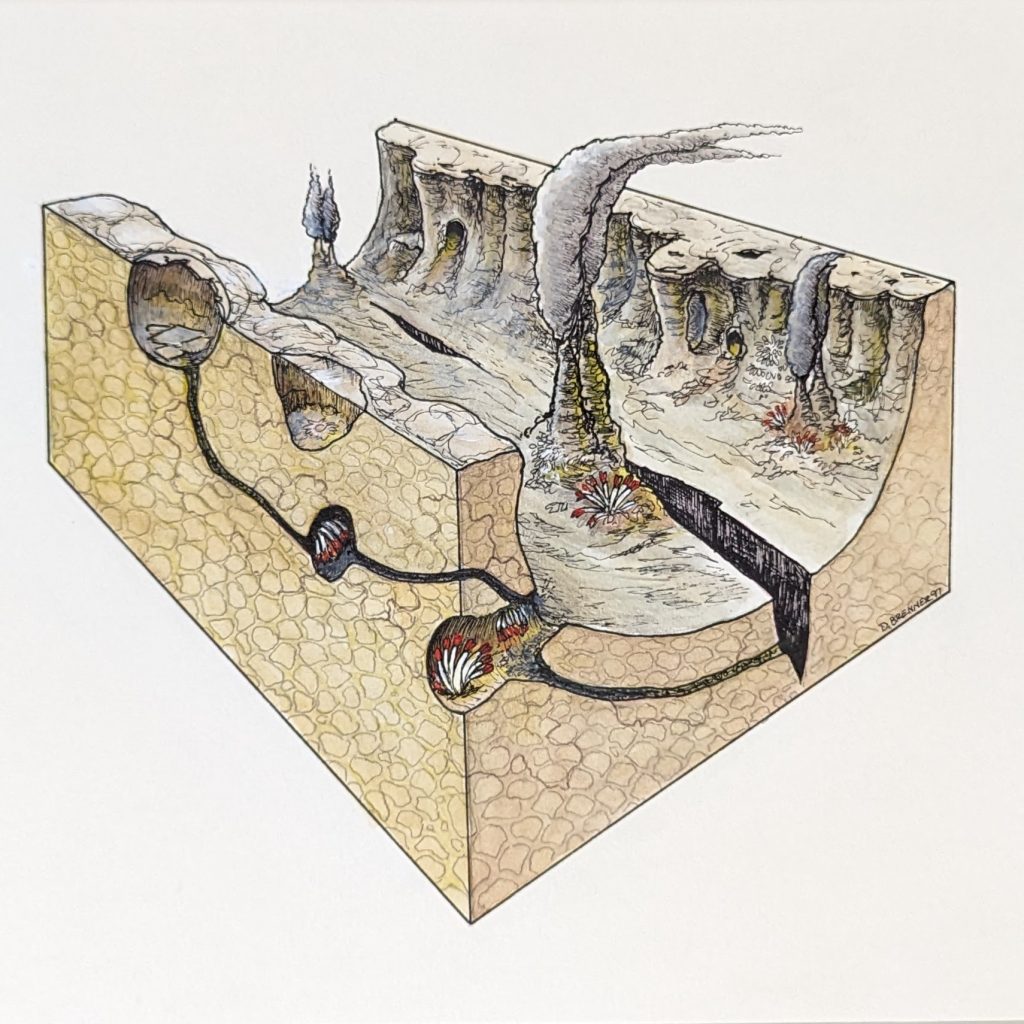

There’s a funny little coda to this discovery. In the paper, the authors provide this tantalizing note: “Transit of larvae through the shallow Earth’s crust in porous volcanic rocks, channels and small subsurface cavities has been suggested (unpublished illustration commissioned by Van Dover 1997), but has to our knowledge never been investigated.”

Two years ago, I took over stewardship over a large portion of my PhD advisor’s sample collection. In addition to tens of thousands of priceless biological specimens, that sample collection came with some amazing deep sea art, much of which is gracing the walls of my office at the Horn Point Lab.

And right there, in the middle, is an unpublished illustration from 1997 featuring giant deep-sea tube worms dwelling within the subseafloor cavities of an active hydrothermal vent field (the illustration is signed D. Brenner ’97, but I don’t have any other information about the artist).

It is a cool little piece of ocean exploration history and a reminder that the deep ocean is still full of surprises.

Southern Fried Science is free and ad-free. Southern Fried Science and the OpenCTD project are supported by funding from our Patreon Subscribers. If you value these resources, please consider contributing a few dollars to help keep the servers running and the coffee flowing. We have stickers.