More people care about marine biodiversity and saving the ocean than ever before. But progress towards evidence-based conservation is hindered by widespread public misunderstanding of the key issues in play.

You’ve heard versions of this rant from me for 15 years, but this is not a post about sustainable fisheries, or shark conservation.

This is a post about the deep sea, and the potential threats to the deep sea’s incredible biodiversity from mining.

Far too many people wrongly believe that nothing lives in the deep sea…and therefore that there’s nothing we need to conserve.

The idea that the deep sea cannot possibly support life was widely popularized by British Naturalist Edward Forbes in the 1840’s as the “azoic hypothesis.” Forbes participated in an early marine biodiversity survey of the Mediterranean and Aegean seas, where he worked to catalogue life found in the ocean. He found lots of life in shallower waters, and a decrease in both biodiversity and biomass as the HMS Beacon sampled deeper water. He extrapolated this data to hypothesize that life can’t exist below 300 fathoms, which we now know is wildly incorrect.

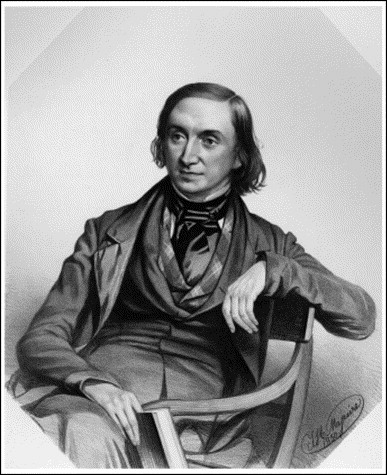

Edward Forbes, as seen in Anderson and Rice 2006.

Most marine biologists learn about this as a brief passing aside about what we used to wrongly believe about the ocean until new evidence became available, if they learn about it at all. However, some of broader context surrounding Forbes’ development of the azoic hypothesis, and how the scientific community and wider public accepted it, is informative.

For example, here’s something that’s been well documented by historians of science, but is not mentioned in any of the introduction to marine biology textbooks I own: scientists had already found life thriving well below 300 fathoms decades before Forbes’ expedition! Some of the most fascinating samples were discovered in 1818 by Arctic explorer John Ross, who, interestingly, was the uncle of Antarctic explorer James Ross, who the Ross Sea is named after.

This specimen of Gorgonocephalus arcticus was sampled by John Ross in 1818.

As seen in Anderson and Rice 2006.

There are also two other key details about the expedition that resulted in the azoic hypothesis that should be better known. Firstly, the Aegean Sea doesn’t just have that much biomass relative to other parts of the ocean—Forbes’ observations are a bit like failing to find lions in Canada and concluding that lions aren’t real. And secondly, the scientific dredges used by the Beacon expedition were inadequate to sample the mostly-small invertebrates that live in deeper waters.

I (and many other marine biologists) were taught that Forbes made a reasonable guess that would later be disproven by new evidence and new technology. In fact, he used the wrong tools to look for life in a small area where there wasn’t that much life, and he ignored already-existing evidence that he was wrong. And Forbes’ wrong view of life shaped scientific understanding of the ocean for decades, and public understanding of these issues for much longer.

Even more troublingly, one could read the original formulations of the azoic hypothesis not as “this is the way things obviously are, I know, I am a scientist and am very smart and I checked,” but “here’s an interesting pattern we observed based on some limited data, someone should check if it’s true more broadly.”

What does a bad idea from nearly 200 years ago have to do with modern conservation issues?

There are many reasons why mining the deep sea is a bad idea that we should not pursue. To me, the most compelling argument is that extractive industries can damage or destroy fragile ecosystems, causing ecological harm, or even a serious risk of extinction, to fascinating and beautiful species found nowhere else.

But making this argument requires that people know that the unique biodiversity of the deep sea exists. Many of the same people who are horrified by the destruction of coral reefs have no objection to deep sea mining, in many cases because they simply didn’t know that anything lives down there.

“Save the whales” is a relatively easy conservation campaign, because everyone knows what a whale is, and many people love whales. “Save the chemosynthetic tube worms” is harder, because you have to start with “what is a chemosynthetic tube worm, and why should we care about them?”

Modern people unaware of the unique organisms found in the deep sea probably aren’t citing the azoic hypothesis of the 1840’s in their arguments, but their ignorance has been implicitly influenced by this bad idea, and it’s wrong interpretations, nonetheless.

Save the deep sea, which is, in fact, full of life.