The middle of America boasts some of the best soils in the world, making it “the breadbasket of America”, if not the world. However, that soil is both a blessing and a curse – native species of grasses and the birds, bugs, and bison that depended on the area have been pushed out in favor of human food production. The ecosystem of middle America looks today like miles upon miles of rows of corn and soy, not the shortgrass prairie that once inhabited the area.

The middle of America boasts some of the best soils in the world, making it “the breadbasket of America”, if not the world. However, that soil is both a blessing and a curse – native species of grasses and the birds, bugs, and bison that depended on the area have been pushed out in favor of human food production. The ecosystem of middle America looks today like miles upon miles of rows of corn and soy, not the shortgrass prairie that once inhabited the area.

Native shortgrass prairie ranged from the Rockies to Nebraska from west to east and Montana to Texas from north to south. The two dominant grass species, blue grama and buffalo grass, flourish under extensive grazing pressure. They are bunch grasses, 12-18 inches high, that can also tolerate relatively low rainfall of 10-12 in.

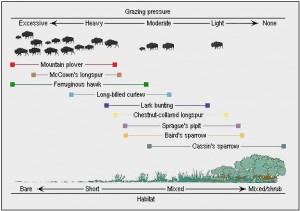

What makes the shortgrass prairie so exciting is that it boasts spectacular examples of coevolution between birds and large grazers, historically, bison. Shortgrass bird life history traits have distinct habitat needs linked to how much a patch of prairie has been grazed.

The history of the shortgrass prairie in ecology highlights the importance of a mosaic landscape to biodiversity, as patches of tallgrass prairie or coniferous trees move are allowed to grow where browsing is light. This supports many species of birds but also grazers such as horses, elk, deer, and bison.

Threats to the prairie today are mostly in the form of agriculture, though mild to moderate ranching takes over the grazing pressure of the historic bison. Of the prairie types, it is the least threatened because of its ability to coexist with, and perhaps dependence on, ranching. In many ways, however, the prairie is taken for granted and conservation efforts are directed elsewhere with the exception of a few foundations like the American Prairie Foundation and efforts to bring back the prairie dog.

Perhaps the greatest tragedy in the shortgrass prairie has already occurred; the removal of the American bison is a black mark in American history for both conservation and indigenous rights. As a result, a few years back some folks came up with the idea of Pleistocene Rewilding to restore the megafauna to the American plains. As crazy as the idea may be, the project made painfully apparent what the prairies are missing; they are missing so much of their land and species that we, as modern humans, have no idea what wonders the shortgrass prairie has to offer.