Whales, those magnificent leviathans of the deep, have an uncanny knack for ending up in space. Science fiction is flooded with stories of starwhales–sometimes entirely new creatures that happen to resemble terran cetaceans in either behavior or appearance, sometimes evolved leviathans from our own world, and occasionally hapless, confused, ordinary whales. This is no fluke. Space is big, whales are big, so why shouldn’t there be whales in space?

Science fiction loves its tropes, and particularly loves comparing space to the golden age of maritime exploration, to the point where starships sometimes have sails. And then, of course, there’s The Narrative. You know, the one where a captain is consumed by obsession and revenge to hunt some semi-mythical mcguffin. If you’re going to do Moby-Dick-in-Space, you better have a starwhale. SciFi loves the Moby Schtick.

So what is a starwhale, and why is it different from other giant space creatures like the exogorth of Empire Strikes Back? Like terran whales, star whales are intelligent creatures that often exhibit some form of emotion. Unlike other space monsters, they often act with a purpose that goes beyond “eat space people, wreck ship”. Nowhere is this more clearly highlighted than in the Doctor Who episode The Beast Below, in which the Doctor encounters the last living starwhale, now supporting the remnants of the British Empire on its back. In the story, the whale endures tremendous suffering in order to protect ‘the children’, and chooses to stay even after being freed from its captors.

Giant whales providing the backbone for mysterious islands traces its roots back to the ancient Greeks, at least in the Western canon. Aspidochelon was a sea monster said to resemble either a turtle or a whale, with a craggy back the carried sandy beaches and sometimes even trees and jungles. Sailors who wandered ashore would find their ships crushed as they were pulled down into the deep. Later incarnations of the whale-as-island made explicit its connection to Satan, the ultimate deceiver. And, of course, Herman Melville makes explicit the modern civilization rests on the back, or, more accurately, the oil, of the whale.

Interestingly, starwhales are, at worst chaotic neutral, but more often lawful good. Their connection to the devil abandoned back on Earth.

The Star Trek universe is resplendent with starwhales, from numerous Enterprises have encountered numerous starwhales, from benign travelers passing through to confused infants looking to the ship for survival, to aggressive bulls threatened by incursion into their territory. Bull sperm whales were documented by early Earth whalers as solitary, especially aggressive male whales, some of which had tasted the bite of many harpoons and continued to charge. It was a bull sperm whale the sunk the Essex, the inspiration for Moby Dick.

While Enterprise had its fair share of starwhale encounters, it was Voyager that experienced the most noteworthy. In one episode, Voyager is mistaken for the rival of an aggressive starwhale forcing the ship to defend itself from the competitive male. The crew find a solution in rolling the ship over and turning blue, which is claimed to be similar to how Earth whales indicate submission. Incidentally, whales lack chromatophores, so it is unlikely that turning blue is any sort of real whale behavioral response. A cursory check of the literature does not indicate much about whale courtship and, in fact, despite centuries of study, whale mating rituals are still largely unknown.

Roger Payne’s Grammy winning recordings of whalesongs are actually included on the Golden Record of the real Voyager spacecraft. A fact which leads into the most notable example of whales-in-space in the Star Trek universe.

Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home is delightful. In it, the original series Enterprise crew rescues the last two humpback whales, loads them into a Klingon Bird of Prey, and flies into the future to respond to an alien probe transmitting whale songs from the actual Voyager. This movie has futureproof synergy.

Fortunately for our future, humpback whales are one of several whale species on the rebound. The international moratorium on industrial whaling has worked. Where once thousands of humpbacks were taken every year, now only a handful succumb to human predation. Recently, proposals have been put forth to remove humpback whales from the US Endangered Species list. For humpback whales, at least, this is a rare case where the actual future is brighter than Star Trek’s vision of utopia Earth.

Incidentally, no NASA did not use whale oil on the Voyager spacecraft.

Since we’ve made the brief segue into whales-in-space, it would be impertinent not to acknowledge the two most hapless space whales in literature. In the Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy, one benighted sperm whale appears above the planet Magrathea, brought into existence by the improbability drive aboard the Heart of Gold, only to be dashed, moments later, upon the planet’s surface. He’s not the only hapless space whale. The killer whale Willzx, of South Park fame, meets a similar fate as he is rocketed into Earth’s moon.

Not all star whales are aimless wanderers through the endless sea of space. Some have chosen to take on passengers, becoming living ships, ferrying their crew across the universe. No star whale is more loyal or more dedicated to her crew of misfits than Moya, the most important character in Farscape. Not all living ships are star whales, some are kludged together from organic parts while others are completely new creatures (or just big, weird bugs with planet-destroying eyeball canons), but Moya is a leviathan, a word that summons visions of mighty whales. Throughout the series, she acts like a whale, fights like a whale, even fights off a rogue leviathan like a whale. Moya is the quintessential star whale.

Incidentally, Earth whales are so large that are able to track them from space, using satellites. Honestly, more often than not, science fact is way more exciting than science fiction.

The Chitauri star whale presents an interesting case. these giant beasts ravaged New York in The Avengers, swimming through the sky via unknown powers. More insectoid than most star whales, they still possessed characteristic mass and behavior, just smart enough to give the Hulk and Iron Man a challenge. Chitauri star whales seemed huge but they weren’t much bigger than the biggest blue whale, the largest vertebrate organism to ever exist. Unlike Chitauri star whales, Blue Whales are filter feeders, the largest animal thrives by consuming some of the smallest. Indeed, it is that aspect of their physiology that prevents the Blue Whale from growing any larger, there’s a huge energy trade-off in filter feeding, and Blue Whales ride the crest of that wave.

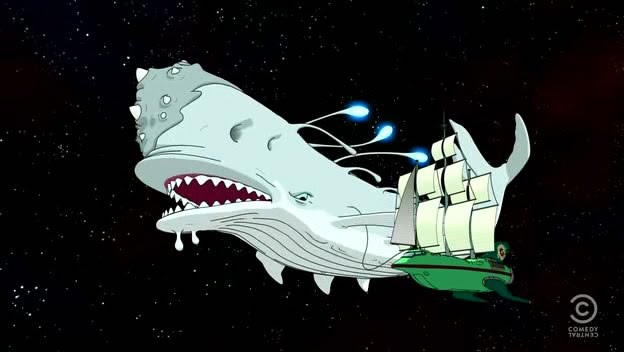

And that brings us the the last iconic star whale in this series, and the Moby-Schtickiest of Moby Schticks, Mobius Dick of Futurama.

Obsession, is the central theme of Melville’s Epic. Obsession is what fuels Mobius Dick, the star whale that eats sea captains obsessed with their mission. And obsession it what has driven industrial whaling into the 21st century, because, as it stands, there is no feasible model to conduct economically sustainable industrial scale whaling (which is not to be mistaken for traditional or aboriginal whaling, which continues to hold significant cultural value and, yes, is a component of self-sufficiency, particularly for arctic communities). Whaling continues into the future, in much the same way that trophy fishing continues, because we have a need to conquer that which is most powerful. Certainly, in our need to rationalize this obsession, we find ways to build both economically and environmentally sustainable models, but the heart of it all is still obsession.

On Earth, we are all Ahab, and we risk carrying that obsession into the stars.

Less famous, but familiar to comic book readers are the Acanti. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Acanti