One of the most common questions I get during my “ask me anything” sessions on twitter is “which species of sharks are the most endangered?” Whenever I can’t completely answer a question in a single tweet, I like to link to more information from a reliable source.

However, I’ve struggled to easily answer this question with a link, because much of the information out there about this particular question is incomplete, misleading, or just wrong. Several online lists of the most endangered species of sharks* don’t actually include the most endangered species of sharks. Many of these lists could be re-titled as “the conservation status of some species of sharks I’ve heard of and could easily find pictures of” or “some random information I heard out of context about shark conservation.” Since there isn’t an easily accessible source of accurate information about this important shark science and conservation topic, I’ll make one myself. ( I should note here that I am referring only to true sharks, not to other chondrichthyans, even though other chondrichthyans in many cases face similar or worse threats. )

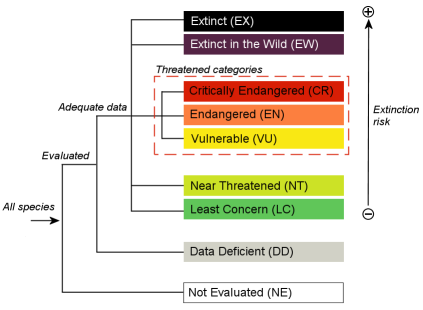

“What species of sharks are the most endangered” is not a matter of opinion, and answering it does not require guesswork by non-expert shark enthusiasts. The IUCN Red List is a global network of scientists and other experts who scientifically and systematically evaluate the conservation status of species using the best available data. (This is not the same thing as a listing under the United States Endangered Species Act). Three Red List categories, Critically Endangered, Endangered, and Vulnerable, are collectively referred to as Threatened, which are the source of the “24% of sharks and their relatives are Threatened” statistic. However, the “most endangered” category is Critically Endangered, which the IUCN Red List defines as “A taxon is Critically Endangered when it is facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future.”

Sharks and their relatives have all been assessed by the IUCN Red List’s Shark Specialist Group, which makes determining the “most endangered sharks” extremely easy using the Red List database’s search tools.

The following ten species of sharks are evaluated as Critically Endangered:

- Pondicherry shark, Carcharhinus hemiodon

- Ganges shark, Glyphis gangeticus

- New Guinea River Shark, Glyphis garricki

- Irawaddy River Shark, Glyphis siamensis

- Natal Shyshark, Haploblepharus kistnasamyi

- Daggernose Shark, Isogomphodon oxyrhynchus

- Striped Smoothhound, Mustelus fasciatus

- Sawback Angelshark, Squatina aculeata

- Smoothback Angelshark, Squatina oculata+

- Angelshark, Squatina squatina

There you go. Those ten are the most endangered sharks species. Any list of “the most endangered shark species” that doesn’t include these Critically Endangered shark species is pretty glaringly wrong. The fact that these ten species are assessed as Critically Endangered and other species aren’t does not mean that all other species are all doing great. However, it does mean that other species are doing objectively, measurably much better than these species.

If you find yourself wanting a longer list, or a list that includes at least some species that you or others are somewhat familiar with, we can expand to shark species assessed as “Endangered.” This category is defined by the Red List as “A taxon is Endangered when it is not Critically Endangered but is facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild in the near future.” It should be noted that a species assessed as “Critically Endangered” is in far worse shape than one assessed as “Endangered.”

The following twenty species of sharks are evaluated as Endangered:

- Borneo Shark, Carcharhinus borneensis

- Smoothtooth Blacktip Shark, Carcharhinus leiodon

- Harrisson’s Dogfish, Centrophorus harrissoni

- Winghead Shark, Eusphyra blochii

- Speartooth Shark, Glyphis glyphis

- Whitefin Topeshark, Hemitriakis leucoperiptera

- Honeycomb Izak, Holohalaelurus favus

- Whitespotted Izak, Holohalaelurus punctatus

- Broadfin Shark, Lamniopsis temminickii

- Narrownose Smoothhound, Mustelus schmitti

- Whale Shark, Rhincodon typus

- Scalloped Hammerhead Shark, Sphyrna lewini

- Great Hammerhead Shark, Sphyrna mokarran

- Argentine Angelshark, Squatina argentina

- Taiwan Angelshark, Squatina formoa

- Hidden Angelshark, Squatina guggenheim

- Smoothback Angelshark, Squatina occulta+

- Angular Angelshark, Squatina punctata

- Zebra Shark, Stegosoma fasciatum

- Sharpfin Houndshark, Triakis acutipinna

These Endangered sharks are in bad shape, but the 10 Critically Endangered species listed above are in far worse shape.

Notably absent from this list (and notably present on many internet lists of the “most endangered sharks” that I come across) is the great white shark. This iconic species is evaluated as Vulnerable, a Threatened category but not anywhere near as bad as Endangered or Critically Endangered. Some populations of Great White Sharks appear to be recovering, but the species still faces significant conservation challenges. That said, claiming that they’re more endangered than, say, Glyphis River Sharks is demonstrably false.

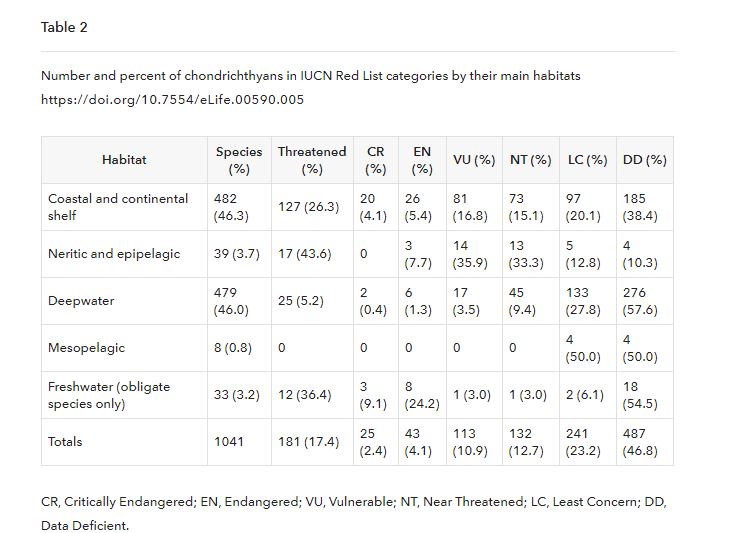

It’s also worth noting that batoids are, overall, in worse shape than sharks.

Where do the most threatened species of sharks live?

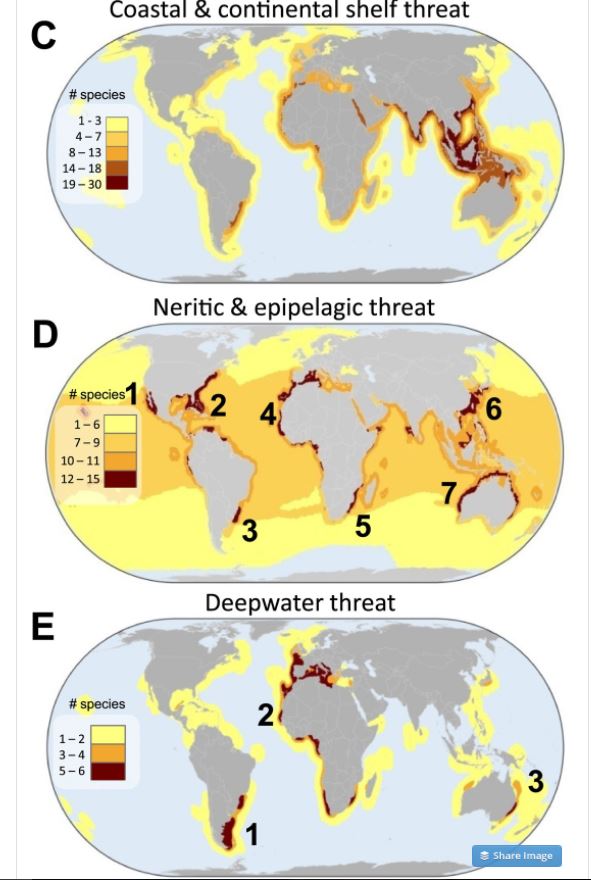

This is also a question that is possible to answer using scientific data and methods: “The megadiverse China Seas face the triple jeopardy of high threat in shallow waters (Figure 7CD), high species richness (Figure 7A), and a large number of threatened endemic species (Figure 8), combined with high risk due to high uncertainty in status (large number of DD species, Figure 7B). Whereas the distribution of threat in coastal and continental shelf chondrichthyans is similar to the overall threat pattern across tropical and mid-latitudes, the spatial pattern of threat varies considerably for pelagic and deepwater species. Threatened neritic and epipelagic oceanic sharks are distributed throughout the world’s oceans, but there are also at least seven threat hotspots in coastal waters: (1) Gulf of California, (2) southeast US continental shelf, (3) Patagonian Shelf, (4) West Africa and the western Mediterranean Sea, (5) southeast South Africa, (6) Australia, and (7) the China Seas (Figure 7D). Hotspots of deepwater threatened chondrichthyans occur in three areas where fisheries penetrate deepest: (1) Southwest Atlantic Ocean (southeast coast of South America), (2) Eastern Atlantic Ocean, spanning from Norway to Namibia and into the Mediterranean Sea, and (3) southeast Australia (Figure 7E).”

Did you follow all that? If not, look at the figures below, which highlight where the highest number of threatened species that live in coastal (C), open ocean (D), and deepwater (E) habitats can be found. Darker colors mean more threatened species live there.

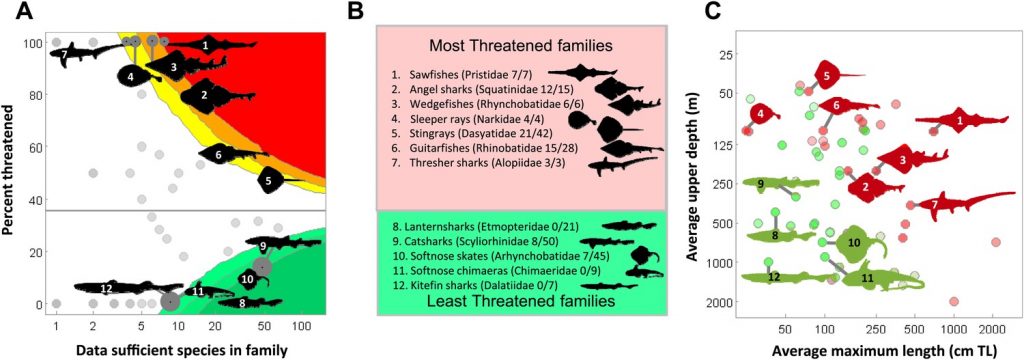

What is the greatest threat facing sharks and their relatives, and are there patterns predicting what species are the most threatened?

According to this same paper by Dulvy and friends, overall, the greatest threat by far facing sharks and their relatives is overexploitation by fisheries, which includes targeted catch and incidental mortality This includes, but is not limited to, fishing associated with the shark fin trade. Supplementary data points out that 12 species are threatened by shark control measures, 24 species are threatened by habitat loss, 22 species are threatened by pollution, and only one is threatened by climate change.

Additionally, this paper notes that “Elevated extinction risk in sharks and rays is a function of exposure to fishing mortality coupled with their intrinsic life history and ecological sensitivity… Most threatened chondrichthyan species are found in depths of less than 200 m, especially in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, and the Western Central Pacific Ocean (79.6%, n = 144 of 181, Figure 2). Extinction risk is greater in larger-bodied species found in shallower waters with narrower depth distributions… The traits with the greatest relative importance (>0.95) are maximum body size, minimum depth, and depth range.”

Conclusions

This stuff matters, you guys. Increased public attention coupled with vocal public support is essential for advancing conservation policies. The shark species at the highest risk of extinction aren’t getting the attention they need, even from eco-friendly media that claims to be highlighting the shark species at the highest risk of extinction.

Readers, you are scientists, conservation activists, and devoted ocean geeks. How many of you had heard of all of these species on the lists above? I hadn’t.

If we are to help protect the species of sharks that need our help the most, we need to do do a better job informing people what those species are.

* For example, three of the five species on this Mother Nature Network list of the top five endangered sharks are not Endangered, and none of them are Critically Endangered. This list regularly pops up on my newsfeed.

+The Critically Endangered Smoothback Angelshark Squatina oculata is a totally different species from the Endangered Smoothback Angelshark Squatina occulta.

At the top of this article is says that you have an “ask me anything” session. I have a question that has been puzzling me for decades: i spend a lot of time at San Nicolas Island off SoCal. The entire island is a rookery, yet in the last 24 years i have never seen a GW there. Any ideas about that??

Glyphis siamensis and Squatina punctata are not valid species. Both have been synonymized in recent years.

Thanks for putting this into a nice, digestible format.

For me, I think my biggest irritation is that people (including some NGOs that should know better), often forget that “sharks” mean more than one species.

Thanks Dave, I will revise the list accordingly next week. Presumably the IUCN Red List plan is to adjust the database entries during the next reevaluation?

As in, “sharks are an endangered species?” Yeah, that’s probably worse than claiming that a great white shark is the most endangered species.