During the Cretaceous, the oceans were ruled not by sharks or aquatic mammals, but by large, predatory marine reptiles. Among these, the dominant ocean predator was the Mosasaur. Mosasaurs emerged in the Early Cretaceous from a lizard-like ancestral squamate. They thrived in warm, shallow seas. Some species could reach up to 17 meters in length. Like modern marine mammals, they breathed air yet had an entirely aquatic life history. Unlike sea turtles and other modern marine reptiles, they gave birth to live young in the water, instead of building nests on land.

During the Cretaceous, the oceans were ruled not by sharks or aquatic mammals, but by large, predatory marine reptiles. Among these, the dominant ocean predator was the Mosasaur. Mosasaurs emerged in the Early Cretaceous from a lizard-like ancestral squamate. They thrived in warm, shallow seas. Some species could reach up to 17 meters in length. Like modern marine mammals, they breathed air yet had an entirely aquatic life history. Unlike sea turtles and other modern marine reptiles, they gave birth to live young in the water, instead of building nests on land.

The phylogeny of Mosasaurs is under dispute. Originally lumped into order Pythonomorpha with other snakes, their placement was later revised to cluster with monitor lizards. Current studies support their original placement in the order Pythonomorpha, along will all extant snakes. Mosasaurs share many characteristics with other pythonomorphids, included an apparent anguilliform swimming style.

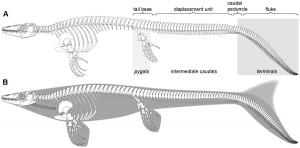

Anguilliform swimmers, like eels and crocodiles, swim by undulating their bodies as opposed to carangiform swimming seen in sharks, whales, and other modern marine predators that generate forward thrust with their tails. Anguilliform swimming is not as efficient as carangiform swimming and results in a slower, less menacing predator. Of the mosasaurs, previously only the most derived species – Plotosaurus – developed carangiform swimming.

A new and beautifully preserved Mosasaur fossil is shedding new light on their swimming abilities. This fossil of Platecarpus – one of the oldest species of Mosasaur, is perfectly preserved with a completely articulated skeleton, impressions of muscle, ligaments, and skin, even putative skin pigments.

This new fossil reveals that Platecarpus – far from being an anguilliform eel wriggling swimmer – had a powerful, shark-like tail to propel it through the water. This made it a much more efficient swimmer and a much deadlier predator. This also dates the evolution of shark-like swimming in Mosasaurs 20 million years earlier than expected.

Of course it’s no surprise that dominant marine predators develop similar body plans. Sharks, dolphins, tuna, and swordfish all have similar propulsion. The ocean is a density limiting environment, there’s only so many ways for large, fast animals to become streamlined. Vertebrates are already limited by their rigid spinal column, and so it’s natural for this type of body form and swimming strategy to evolve multiple times across diverse taxonomic groups.

Evolution is a weird and wonderful thing.

~Southern Fried Scientist

Lindgren, J., Caldwell, M., Konishi, T., & Chiappe, L. (2010). Convergent Evolution in Aquatic Tetrapods: Insights from an Exceptional Fossil Mosasaur PLoS ONE, 5 (8) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011998

Lee, M. (1997). The phylogeny of varanoid lizards and the affinities of snakes Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 352 (1349), 53-91 DOI: 10.1098/rstb.1997.0005

Crescent-shaped tails were way cooler when only sharks had them. Then they sold out and started showing up on ichthyosaurs, swordfish, tuna, now mosasaurs…

In all seriousness, that’s some pretty awesome convergent evolution.

gotta love the fusiform bauplan. But seriously, remember when sharks were cool?

Clearly sharks get the indie cred. They’re the Pixies to the dolphins’ Nickelback, which would put mosasaurs in somewhere around Stone Temple Pilots.

Dude, I was in to fossils when they were still under ground.

Crescent-shaped tails were way cooler when only sharks had them. Then they sold out and started showing up on ichthyosaurs, swordfish, tuna, now mosasaurs…

In all seriousness, that’s some pretty awesome convergent evolution.