Lest you think aquaculture is like your childhood fish tank on a larger scale, let me remind you of the plecostomus in that tank. You know, the thing that sat stuck to the back of the tank behind the plant so that the family could never quite find it. Yet somehow, despite the fact that you could swear it never moved and could have been a stone decoration rather than an organism, this little helper kept every surface of that tank sparkly clean. Algae-free glass, gravel, and plants. But what if you have large, outdoor ponds and each mouth to feed costs you money if it doesn’t eventually end up as dinner?

Lest you think aquaculture is like your childhood fish tank on a larger scale, let me remind you of the plecostomus in that tank. You know, the thing that sat stuck to the back of the tank behind the plant so that the family could never quite find it. Yet somehow, despite the fact that you could swear it never moved and could have been a stone decoration rather than an organism, this little helper kept every surface of that tank sparkly clean. Algae-free glass, gravel, and plants. But what if you have large, outdoor ponds and each mouth to feed costs you money if it doesn’t eventually end up as dinner?

This is exactly when you have to stop thinking of these operations as just a tank of fish. They are nestled in the surrounding ecosystem, full of naturally occuring algae – some good and some bad. For eastern North Carolina, both the wind and the tide might carry in some future algae blooms to your tanks, which are well-stocked with nutrient-rich fish poop to feed it. Instead, as NC Aquaculture Conference speaker DE Brune puts it, you have to think of your tanks and ponds as “designed ecosystems”.

Dr. Brune told his scientific story as a personal travelogue as he moved through school and then several professorships across the country. Each place and set of people added something to his story. A great way of thinking about the development of aquaculture, I overheard many subsequent conversations praising the storytelling style and the content of those lessons – the trials and tribulations with algae, but also the great potential for algae to be a productive member of the aquaculture family.

After concluding “this lab data is not useful to growing algae in the field at all”, Dr. Brune has spent a career committed to making his experiments relevant to the size of commercial operations – sometimes to the chagrin of the university’s administration. His emphasis for this is only rivaled by his commitment for using biological means of algae harvesting rather than the more engineered mechanical approaches. “Why not use a critter that spent millions of years figuring out how to convert algae” he asked, referring to brine shrimp or “sea monkeys” as you may have known them as a child.

Brune put up a slide showing two beakers – one full of bright green algae, the other full of brown feathery brine shrimp. It took 15 minutes to get from one state to the other, and then the relevant oils for biofuels can easily be extracted from the shrimp. This is the alternative he proposes to the traditional filtering that involves boiling and extracting with large quantities of hexane – at a huge energy expense and exposure to toxin for employees.

Growing algae on purpose takes skill and careful manipulation, however, a process Brune called “controlled eutrophication”. A system full of algae can quickly flip over the threshold from healthy green to brown nitrifying bacteria, and seemingly “always in the middle of the night”. More seriously, the aeration demand goes up before any visible signs show up, so growers have to be ready to pounce on problems the minute they arise.

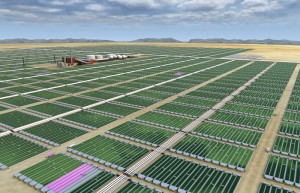

Part of the interest in growing algae is in the hopes of harnessing their photosynthesis to capture CO2 from traditional power plants, turning it into liquid fuel. By Brune’s calculations, a relatively small 50 MW plant would require 2000 acres of algae in order to capture all of the carbon released. Not to mention algae only grows during daylight hours, but power plants continue burning fossil fuels through the night.

Instead, algae might fit better as part of a diversified aquaculture economy. The algae produce oxygen for the fish – and if the right kind is cultivated from the ambient environment, make them taste better – then can be harvested for fish feed and biofuel production. These last two byproducts could potentially make up 30% and 10% of the operation’s revenue, respectively, with the fish themselves making up the remaining 60%. He also suggests tilapia in the mix to take care of solids that make their way to the bottom of the tank. In a truly designed ecosystem, all the parts serve a purpose and could make the farm some money. That’s the goal, at least. Check in with Dr. Brune after this coming summer to see if his current test farm can live up to the challenge.