The term sustainability is a muddy one, covered in marketing efforts and political baggage. So when someone says they study sustainability or are part of the field of sustainability science, what does that mean? The discipline actually refers to a fairly well-defined subject borne out of the call for interdisciplinary research, especially between ecology and the social sciences. At its heart, the field is based in the need to provide food, fuel, and fiber to current and future residents of planet earth. In other words, it’s the science behind the Brundtland Commission’s oft-cited goals of sustainable development and hopes to understand and create long-term integrity of the biosphere and human well-being.

The term sustainability is a muddy one, covered in marketing efforts and political baggage. So when someone says they study sustainability or are part of the field of sustainability science, what does that mean? The discipline actually refers to a fairly well-defined subject borne out of the call for interdisciplinary research, especially between ecology and the social sciences. At its heart, the field is based in the need to provide food, fuel, and fiber to current and future residents of planet earth. In other words, it’s the science behind the Brundtland Commission’s oft-cited goals of sustainable development and hopes to understand and create long-term integrity of the biosphere and human well-being.

Author: Amy Freitag

Amongst my field gear is a buzz off shirt, hat, and bandana that were purchased in Alaska to ward off the state bird – the mosquito. Upon arriving to Fairbanks, I realized within the space of a few days that I would need some better bug gear for my tenure there and found a local store stocked with an entire floor of their store featuring buzz off gear.

Amongst my field gear is a buzz off shirt, hat, and bandana that were purchased in Alaska to ward off the state bird – the mosquito. Upon arriving to Fairbanks, I realized within the space of a few days that I would need some better bug gear for my tenure there and found a local store stocked with an entire floor of their store featuring buzz off gear.

Ex Officio definitely has a style that carries over into their bug gear, making it a cross between travel gear and classic field clothes. I kind of wish they had included their travel pockets in the shirt, for instance. But they’ve included the buzz off chemical, whatever that may be, into their quick-dry cloth, meaning that you can wash and wear while traveling.

The focus on community and informal rules that were found to frequently structure successful commons management made apparent that the word ‘policy’ needed to be expanded. Policy scholars now look beyond the official written laws, reports, and regulations that are often written by a central government to multi-scalar rules that govern the structure and behavior in a system (Ostrom 2005). They include non-written cultural norms, religious prescriptions, and community ethics that are often more strongly followed that written, formal rules (Berkes 2008). Along with a more broadly defined concept of policy, commons scholars also introduced a more broad definition of institution within which these policies are made and enforced. Much like policies, institutions can be governmental as well as religious, moral, or cultural. Hanna and Jentoft (1996) give an appropriately broad definition for natural resource institutions: “institutions represent the arrangements which people devise to control their use of the natural environment”. Ostrom (2005) promotes an institutional analysis in order to encompass these new conceptions of policy and institution. Her work recently earned the Nobel prize and is rapidly becoming the most used framework for policy analysis.

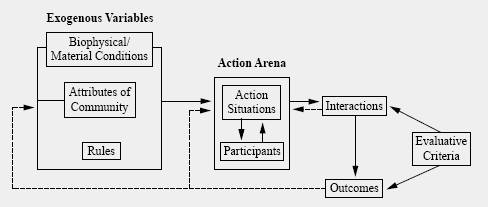

Ostrom’s Institutional Analysis and Design (IAD) Framework is not specific for natural resources or even commons problems, but serves as a place to begin policy analysis for all sorts of policy problems, including education, gender relations, crime, and natural resources. A short description here does not fully describe the IAD framework – for that, refer to Ostrom’s 2005 book. To highlight a few pertinent features, the framework is centered around a decision-making arena called the action arena rather than on the formation of a particular policy. Inputs to the action arena include exogenous variables describing the biophysical characteristics, community factors, and existing rules relating the action arena in play. This action arena then interacts with action arenas at other levels of governance (operational, collective choice, constitutional, and super-constitutional) to form an outcome. The outcome is evaluated by some defined set of criteria and the process feeds back to become iterative. The main benefit of the framework is to allow for comparative studies between empirical studies by scholars around the world in many disciplines.

Ostrom’s Institutional Analysis and Design (IAD) Framework is not specific for natural resources or even commons problems, but serves as a place to begin policy analysis for all sorts of policy problems, including education, gender relations, crime, and natural resources. A short description here does not fully describe the IAD framework – for that, refer to Ostrom’s 2005 book. To highlight a few pertinent features, the framework is centered around a decision-making arena called the action arena rather than on the formation of a particular policy. Inputs to the action arena include exogenous variables describing the biophysical characteristics, community factors, and existing rules relating the action arena in play. This action arena then interacts with action arenas at other levels of governance (operational, collective choice, constitutional, and super-constitutional) to form an outcome. The outcome is evaluated by some defined set of criteria and the process feeds back to become iterative. The main benefit of the framework is to allow for comparative studies between empirical studies by scholars around the world in many disciplines.

Read More “State of the Field: A New Type of Policy Analysis” »

At the end of each summer, I generally have a distinctive “z” shaped tan on my feet from wearing Chacos almost every day. I originally got a pair upon the suggestion of a friend on my field crew while working in Olympic National Park and that pair lasted me almost 5 years. They became my best friend as a sandal in which I could walk up fairly large hills and with which I could backpack in the summers. Much like many of my shoes, they also work well around town or while traveling since they look fairly nice as well.

At the end of each summer, I generally have a distinctive “z” shaped tan on my feet from wearing Chacos almost every day. I originally got a pair upon the suggestion of a friend on my field crew while working in Olympic National Park and that pair lasted me almost 5 years. They became my best friend as a sandal in which I could walk up fairly large hills and with which I could backpack in the summers. Much like many of my shoes, they also work well around town or while traveling since they look fairly nice as well.

A few years back I attended a mid-field season gathering of researchers working on International Polar Year projects. We were lucky enough to have collected the marine biologists, recently returned from a short cruise out of Barrow, AK with the mission to describe the biota living on the underside of the sea ice that is so critical to terrestrial Arctic ecology. It was absolutely stunning to me to realize that there is a whole ecosystem associated with the bottom of the ice, an ephemeral, threatened resource.

A few years back I attended a mid-field season gathering of researchers working on International Polar Year projects. We were lucky enough to have collected the marine biologists, recently returned from a short cruise out of Barrow, AK with the mission to describe the biota living on the underside of the sea ice that is so critical to terrestrial Arctic ecology. It was absolutely stunning to me to realize that there is a whole ecosystem associated with the bottom of the ice, an ephemeral, threatened resource.

Depending on the time of year, sea ice covers 3-7% of the planet, making this relatively unexplored ecosystem fairly important to global biogeochemical processes. The algae trapped in and under sea ice, for example, accounts for 25% of the Arctic’s and 20% of the Antarctic’s primary productivity. This productivity trickles up the food web to the more well-known ice dwellers, such as polar bears and seals.

Ever stop to think what divides the first from the third world? Why don’t we ever hear about the second and why don’t countries move between categories as they develop? Well, because the categories are historical – the second world is reserved for post-soviet countries attempting to rebuild governance. The first world is reserved for those who shone through as leaders at the end of World War 2. The third world – everybody else. But what does that mean for development research? And what about those places within our own country without running water and electricity?

![]() Looking inward to the researcher’s own countries means questioning the benefit of some institutions that are part of the dominant narrative of success in those countries. Before any differences are made explicit between investigation of the First and Third World, there is the question of outsider/insider position that must be attended to. Identifying and challenging assumptions as an insider may prove much more difficult than analysis of a foreign society as an outsider (Perin 1977). For example, community forestry in Canada was assumed to not exist because Canada is fully embedded in a capitalist economy, but was discovered to be successfully functioning in British Columbia, largely due to a regional difference in values diverging from capitalism (McCarthy 2006).

Looking inward to the researcher’s own countries means questioning the benefit of some institutions that are part of the dominant narrative of success in those countries. Before any differences are made explicit between investigation of the First and Third World, there is the question of outsider/insider position that must be attended to. Identifying and challenging assumptions as an insider may prove much more difficult than analysis of a foreign society as an outsider (Perin 1977). For example, community forestry in Canada was assumed to not exist because Canada is fully embedded in a capitalist economy, but was discovered to be successfully functioning in British Columbia, largely due to a regional difference in values diverging from capitalism (McCarthy 2006).

Perin (1977) suggests analyzing controversies to identify such assumptions that may also inherently be part of the inside researcher’s worldview. First World political ecologists have focused on controversies, largely looking at land use or resource management controversies. In the process, they have identified different processes at work in the First World than the Third World. These differences add a few key concepts to the political ecology toolbox: a need to explicitly recognize heterogeneity in a seemingly unified nation (St. Martin 2001), the role of a strong central state (Walker 2003), the role of larger capitalist economy and culture (Escobar 2004), and the process of rural gentrification (Schroeder 2005).

Perin (1977) suggests analyzing controversies to identify such assumptions that may also inherently be part of the inside researcher’s worldview. First World political ecologists have focused on controversies, largely looking at land use or resource management controversies. In the process, they have identified different processes at work in the First World than the Third World. These differences add a few key concepts to the political ecology toolbox: a need to explicitly recognize heterogeneity in a seemingly unified nation (St. Martin 2001), the role of a strong central state (Walker 2003), the role of larger capitalist economy and culture (Escobar 2004), and the process of rural gentrification (Schroeder 2005).

Read More “State of the Field: First World or Third World?” »

A field vehicle can be just a means of shuttling gear or a home away from home. Most people think of a rough and tumble truck tackling aged logging roads, but depending on your needs and your discipline, something different might play the role. For instance, I work relatively close to home as all of my field sites are less than three hours away by highway and any sample collecting occurs on the water, generally in a borrowed boat (something this series will come to later).

A field vehicle can be just a means of shuttling gear or a home away from home. Most people think of a rough and tumble truck tackling aged logging roads, but depending on your needs and your discipline, something different might play the role. For instance, I work relatively close to home as all of my field sites are less than three hours away by highway and any sample collecting occurs on the water, generally in a borrowed boat (something this series will come to later).

We as humans and especially here at SFS like to picture an ideal government and hope that as we learn more about science and political theory, government can take steps in that direction. By any measure, governance within the United States is far from meeting the theoretical ideal. Implementation and enforcement are often pointed at as more important factors than policy design in terms of effectiveness in meeting policy goals. But if we ever had the chance to change the design, here’s four principles that will help make sure we move in the right direction.

We as humans and especially here at SFS like to picture an ideal government and hope that as we learn more about science and political theory, government can take steps in that direction. By any measure, governance within the United States is far from meeting the theoretical ideal. Implementation and enforcement are often pointed at as more important factors than policy design in terms of effectiveness in meeting policy goals. But if we ever had the chance to change the design, here’s four principles that will help make sure we move in the right direction.

Addressing Scale: Appropriate information gathering

If scale is unified at the ecosystem level – bounded by hydrological and geophysical boundaries – then information about the system must also represent the ecosystem scale. Fisheries management, for example, requires information on all the potential factors that could affect stock size – habitat, water quality, fishing pressure, competition with other native and nonnative species, productivity of the food web, etc. Furthermore, the total fishery stock in an area would have to be considered together – total biomass of market species, for example. These types of measurements will delineate threats to conservation to a particular species versus threats to the health of the whole system.

Following our discussion of scale, management boundaries must match ecological processes which are now recognized to be dynamic and complex. This means that management must manage not for a known equilibrium, but a dialectic system full of uncertainty (Berkes 2008). Instead of attempting to predict from the instigation of a policy what the effects may be, governance should be structured to constantly evaluate the system and incorporate feedbacks. This process, known as adaptive management (also check out statements on the subject from the Resilience Alliance and US Department of Interior), provides for the co-evolution of the system and its governance to ensure that they remain an effective match.

Under adaptive management, episodes of disturbance are learning opportunities, not a signal of policy failure. Berkes (2008) describes this phenomenon: “’conservation’ is not a state of being. It is a response to a people’s perceptions about the state of their environment and its resources, and a willingness to modify their behaviors to adjust to new realities”. He goes on to say that disturbances are not only opportunities for learning, but that they are necessary for that learning to occur. Gunderson and Carpenter (2006) add that disturbance is necessary for transformational learning – the type of learning that allows for the emergence of novelty. Therefore, disturbances should be allowed to occur in order to foster community and governmental innovation.

Everyone’s seen the Keen sandals – the ones that characterize the feet of kayakers all over and arguably create their own style. Keen, however, also offers shoes more in line with their motto of “hybrid life” – that is, they are supposed to be good for a life on-the-go for someone who only wants to carry one pair of shoes.

Everyone’s seen the Keen sandals – the ones that characterize the feet of kayakers all over and arguably create their own style. Keen, however, also offers shoes more in line with their motto of “hybrid life” – that is, they are supposed to be good for a life on-the-go for someone who only wants to carry one pair of shoes.

I received such a pair as a birthday gift from my mother – the source of most shoes in my life. She bought them because they were “cute” and because they came in green, a color that pervades my wardrobe. So they’ve passed the mom test on style. How’d they do on function?