Earth is facing a biodiversity crisis so severe that many conservation scientists refer to it as a mass extinction event. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a professional network of 11,000 volunteer scientists belonging to more than 1,000 government and NGO agencies in 160 countries, evaluates species worldwide and determines their risk of extinction. This Red List, which ranks species in increasing risk of extinction – Least Concern, Near Threatened, Conservation Dependent, Vulnerable, Endangered, Critically Endangered, Extinct in the Wild, and Extinct – is described as “the world’s most comprehensive information source on the global conservation status of plant and animal species”.

Earth is facing a biodiversity crisis so severe that many conservation scientists refer to it as a mass extinction event. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a professional network of 11,000 volunteer scientists belonging to more than 1,000 government and NGO agencies in 160 countries, evaluates species worldwide and determines their risk of extinction. This Red List, which ranks species in increasing risk of extinction – Least Concern, Near Threatened, Conservation Dependent, Vulnerable, Endangered, Critically Endangered, Extinct in the Wild, and Extinct – is described as “the world’s most comprehensive information source on the global conservation status of plant and animal species”.

Statistics from the Red List are terrifying. One fifth of all evaluated vertebrate species are threatened with extinction, including 12% of birds, 21% of mammals, 30% of amphibians, and 26% of fish. On average, fifty species of amphibians, birds, and mammals move measurably closer to extinction each year. One fifth of the world’s plant species are in danger of extinction. Critical habitat-builders, including 33% of reef building coral species and 14% of seagrass species are in very big trouble.

One of the most threatened groups of animals are amphibians (1,895 in danger of extinction out of 6,285 known species), and they are facing a different threat entirely. First described in Australia in 1993, Chytridiomycosis – a devastating amphibian disease caused by the chytrid fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis – has spread around the world. Some estimates have this disease affecting up to 30% of amphibian species worldwide. Spores enter the skin of the host, progress rapidly, and result in a sloughing of the skin, ulcers, and hemorrhages. In many populations Chytridiomycosis results in nearly 100% mortality. Global climate change is altering the range of this fungus and exposing new amphibian populations.

Even when compared to the global biodiversity crisis as a whole, sharks are doing extremely poor. According to IUCN Shark Specialist Group co-chair Dr. Nick Dulvy (Simon Fraser University), “Less than a quarter of the world’s sharks, rays, and chimaeras are safe – there is a real chance that our grandchildren will know many sharks only from photographs.”

Numerous threats are facing the world’s wildlife, and most of them result from human activity. The Red List summarizes these threats:

* Habitat loss and degradation affects 86% of all threatened birds, 86% of the threatened mammals assessed and 88% of the threatened amphibians.

* Introductions of Invasive Alien Species that establish and spread outside their normal distribution. Some of the most threatening invasive species include cats and rats, green crabs, zebra mussels, the African tulip tree and the brown tree snake. Introductions of alien species can happen deliberately or unintentionally, for example, by organisms “hitch-hiking” in containers, ships, cars or soil.

* Over-exploitation of natural resources. Resource extraction, hunting, and fishing for food, pets, and medicine.

* Pollution and diseases. For example, excessive fertilizer use leads to excessive levels of nutrients in soil and water.

* Human-induced climate change. For example, climate change is altering migratory species patterns, and increasing coral bleaching.

Though it is getting worse, scientists and natural resource managers have known of this crisis for decades. The convention on biological diversity created a series of 2010 Biodiversity Goals, which include promoting sustainable use of natural resources, controlling invasive species, reducing pollution, protecting species from climate change, and other worthy objectives. According to many environmental groups, world governments have failed to meet these targets.

In many cases, conservation biologists have proposed solutions that we believe will help these threatened animals. These often have negative economic consequences, and can be incredibly unpopular with the general public. Additionally, though they represent the best available science, their efficacy cannot be assessed without trials.

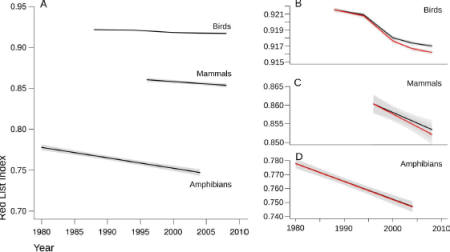

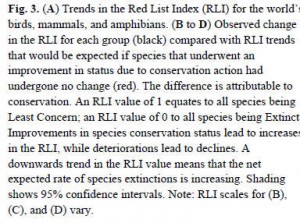

The IUCN has evaluated the conservation status of nearly 56,000 species, and has tracked many of them since the first Red List in 1994. This makes Red List data an excellent source of information on whether or not certain conservation initiatives accomplish their goals. Released to correspond with a Convention on Biodiversity Meeting in Nagoya, Japan (in which we are setting our 2020 biodiversity goals), a recent paper in Science addresses this very question. This massive undertaking represents more than ten years of date, involves 174 authors from 38 countries, and its conclusions are broad reaching and relevant to everyone working in conservation.

928 species changed their Red List status. While many of these have been deteriorating, 68 (approximately 7%) have improved in status. 64 of these 68 have improved their status as a direct result of conservation action.

In addition, modeling shows that without conservation, bird and mammal species decline would have been 18% worse. In other words, 29 species of mammal were prevented from declining on the Red List as a result of conservation measures. As Harriet Nimo, Chief Executive of WildScreen, says, “While the outlook for many species is still grim, this report is a testament to the real and valuable impact conservation work can have.”

These estimates are low, since they don’t factor in that many species’ populations improved as a result of conservation but not enough to improve their Red List status. It also doesn’t factor in that many species were prevented from declining because of conservation measures.

In addition to summarizing broad trends, the paper discusses many individual threatened species that have been brought back from the brink of extinction as a result of conservation policies.

The California Condor (Gymnogyps californianus), North America’s largest bird, is a classic success story. When conservation measures were introduced in 1987, the wild population of condors had been reduced to 22 due to lead poisoning, poaching, and habitat loss. These survivors were rounded up and bred in captivity. Condors were reintroduced to the wild in 1991 and their current population stands at 384, with 188 in the wild.

The black-footed ferret (Mustela nigripes) is found on the North American prairie. They were declared extinct in the wild until a new colony was discovered and taken into captivity in 1985. Breeding programs have successfully reintroduced the ferret into it’s environment and the population now stands at approximately 750 in the wild and 250 in captivity.

The Przewalski’s Horse(Equus ferus przewalskii) is the last truly wild species of horse on the planet. Native to Central Asia, it was declared extinct in the wild, although captive breeding programs have successfully reintroduced it into its native habitat. Today there are over 100 extant Przewalski’s Horses.

Though amphibians are, overall, the group that is doing the worst, at least one species is making a comeback- the Kihansi Spray Toad. Captive-bred populations are being released into their native Tanzanian habitats.

Though captive breeding programs are a commonly used (and often successful) conservation strategy, the paper also covers other initiatives.

Elimination of invasive predators can also make a big difference. Elimination of brown rats (Rattus norvegicus) has helped bring the Seychelles Magpie-robin (Copsychus sechellarum) back from the brink. Since these animals evolved in an environment without rats, they have no defenses against them. Rat predation brought the population down to a low of 15 birds in 1965. Thanks to rat-control measures, the population is now 180 birds.

For many species, captive breeding isn’t an option, and the main predators threatening them are humans. This was once the case with whales like the humpback (Megaptera novaeangilae), which were hunted nearly to extinction. Another type of conservation policy, a ban on hunting, brought these whales from “threatened” status to “least concern”.

The paper also addresses which conservation measures are effective and which need improvement. One of the more successful policies has been elimination of invasive predators on small islands (two status improvements for every five status declines). While extremely important for certain endangered birds and mammals, this has limited application for a large parts of the world. One of the areas where conservationists have had the least success is reducing habitat loss (less than one status improvement for every ten status declines for species threatened by habitat loss). While protected areas are an effective tool, they won’t fix this problem unless we locate them where threatened species are, have a lot more of them, and ensure effective enforcement. Despite some legal protections and conservation success stories, hunting of mammals and birds remains a major threat. There are also relatively few conservation efforts directed at amphibians.

Much of the success of some of these conservation may come from island effects. Species whose habitat ranges are already patchy may be more resistant to increased patchiness, a trait that gives them more resilience to human induced pressures. These resilient species have a better chance of recovering when conservation efforts relieve those pressures. Among the notable success stories are many classical island species – literal islands, swamp hammocks, patches of abundance in desert ecosystems, and many others. The failure of many conservation measures to succeed for broad ranging species is a testament to the resilience of island systems.

The significance of this paper cannot be overstated. Julia Marton-Lefevre, Director General of IUCN says “It is a clarion call for all of us – governments, businesses, citizens – to mobilize resources and drive the action required. Conservation does work — but it needs our support, and it needs it fast!”

Thanks to the IUCN and this important new paper, scientists and conservationists have a powerful new weapon in the fight to shape public policy. The world’s biodiversity crisis is worsening, but we have effective solutions. We now have documented proof that well supported conservation efforts are effective at protecting threatened species. This research shows that stopping habitat loss via protected areas is effective but underutilized. It shows that it is possible to remove the threat of an invasive predator. It shows that hunting bans allow threatened animals to rebound. Used properly, this research should help new conservation efforts to gain the support they need, and we don’t have any time to waste.

~WhySharksMatter and Southern Fried Scientist

Hoffmann, M. et al. (2010). The impact of conservation on the world’s vertebrates Science

I would like to thank Dr. Nick Dulvy of the IUCN Shark Specialist Group for all of his help with this post.

I like the focus being on conservation successes rather than where we need to work. Obviously, call-to-action articles are important, but it’s also important to show how far we’ve come and what we’ve done right, though I was a little disappointed that Kakapos didn’t make the list…haha.

Of course, by focusing on vertebrates, they’re pretty much tacitly acknowledging that when it comes to inverts, you’re either data deficient or already extinct.

Or acknowledging that endangered mammals and birds get more press coverage than inverts. The IUCN does cover inverts sometimes.

From another article:

“Invertebrate species, especially in locations like the Amazon Basin, are going extinct at an alarming rate. Over half of those evaluated are now listed as threatened or endangered by the IUCN, with crustaceans accounting for the highest percentage. Habitat loss seems to be the major reason invertebrate species continue to vanish. “

Interesting that you interpreted that as “everyone pays attention to mammals and birds” as opposed to “invertebrates are much more complex, difficult to assess and manage, and so for the most part they’re either data deficient or already extinct.” The success stories for inverts are few and far between, not because vertebrates get more press, but because inverts are in much worse shape. How many of those species that improved in status were invertebrates?

Bingo. Reef building corals probably have more sex appeal than Przewalski’s Horse, but corals are in a death spiral with no end in site.

That too.

Doesn’t the “Law of Evolution” demand that these animals adapt and survive? Oh, wait, that takes millions of years. How did that work, again? Why is it that millions of years ago animals could adapt to difficult conditions, but today they seem to have lost that ability?

No, evolution doesn’t ‘demand’ anything.

You may be interested in the Talk Origin article – Introduction to Evolutionary Biology for an easy to understand refresher on the basics of the Theory of Evolution.

What evidence do you have that they’ve lost the ‘ability’ (whatever that means) to evolve? Are you 100% genetically identical to your mother? Organisms are adapting to environmental changes all the time, but, just like millions of years ago, some groups will go extinct and some will survive.

Regarding questions above, to the point answers. (like) So happy people like yourself and others, are helping to save our ocean habitat and wildlife, which are absolutely on the brink, and we have to intervene to help.

John Pokley,

There is a moral dimension to your question. Science shows us that human activity is responsible for the currently rapid evironmental changes that are driving these increasing extinctions. Under these human-caused (anthropogenic) conditions, many more of these species will not survive if we don’t make some changes to the way we are living our lives. What of this do you believe is your responsibility? Have you really stopped to consider the effects of these potential extinctions? Do you realize that around 20 species of plants and animals stand between current human population and almost complete human civilization collapse? Have you considered the effects of anthropogenic global climate change on human civilization if we continue to ignore the problem?

Or do you deny the science that shows that these changes are anthropogenic?

If you don’t, then do you believe you are in any way morally responsible for taking part in such actions?

If not, why not?

The truth of the matter is that life will survive. This has all happened before, though it has never been caused by the conscious ignorance of just one species until now. But we are one of the more increasingly vulnerable species to the changes we are causing. If we can’t (or won’t) change the way humans are currently over-exploiting natural resources, the humans may go long before many more truly adaptable species, like insects, bacteria, nematodes, algea, or fungi, to name just a few.

I really don’t think you want to make that challenge of “adapt and survive” to the fungi.

By the way, Andrew and David, this is an excellent post!