The claim: Deep-sea Anglerfish have parasitic dwarf males that fuse to their mates and become nothing more than wibbly gonads hanging off of the much larger female.

Who said it: Well, pretty much everyone. This Oatmeal Comic, Ze Frank, me.

Status: Sometimes true, sometimes false.

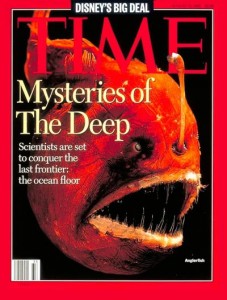

I’d like you to meet a very dear friend of mine. This is Melanocetus johnsonii, the humpback anglerfish. If you follow the deep sea at all, you’ve probably met this delightful creature. She was featured on the cover of time magazine, barely losing out to Newt Gingrich for 1995 Vertebrate of the Year. Since then, she has been a standard-bearer for the deep sea, an iconic species, immediately recognizable. Stories of her exploits abound, and no story is more compelling that the tale of the hapless male anglerfish, a parasitic dwarf that lives its entire adult life fused to the larger, more capable female angler fish.

I’d like you to meet a very dear friend of mine. This is Melanocetus johnsonii, the humpback anglerfish. If you follow the deep sea at all, you’ve probably met this delightful creature. She was featured on the cover of time magazine, barely losing out to Newt Gingrich for 1995 Vertebrate of the Year. Since then, she has been a standard-bearer for the deep sea, an iconic species, immediately recognizable. Stories of her exploits abound, and no story is more compelling that the tale of the hapless male anglerfish, a parasitic dwarf that lives its entire adult life fused to the larger, more capable female angler fish.

There’s just one problem.

Melanocetus johnsonii, along with the four other anglerfish that make up genus Melanocetus, don’t have parasitic males. Males of this genus are still significantly smaller and lack lures, but they retain their free-swimming lifestyle into adulthood, occasionally biting into the side of a much larger female for a temporary coupling, where gametes and food are exchanged. This temporary coupling, in which no tissue fusion takes place, has been observed only three times: once during the filming of the BBC Blue Planet documentary; once off the coast of Japan; and once, confusingly between a male Melanocetus johnsonii and a completely different species, Centrophryne spinulosa. In none of these instances was the connection permanent, and no reduced males have even been found attached to a Melanocetus.

So, unfortunately for fans of the Oatmeal and Ze Frank, this particular anglerfish is not the icon of male parasitism you were hoping for. Try Haplophryne mollis, instead.