The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

DS: Why was Support Our Science Founded? What the state of affairs for Canadian science that made you say “this has to change?”

Sarah Laframoise, University of Ottawa, Executive Director of Evidence for Democracy and co-founder of Support Our Science: Two years ago, I spoke for the first time as a witness in a standing committee for science and research, for their first study on finding and retaining top talent. At the time, I had just started the Ottawa Science Policy network and we had just wrapped up a survey on graduate student finances in Canada, which surveyed about 1300 students. Some of the responses we were getting were worse than we could have imagined. About 30% were considering dropping out of graduate school due to financial concerns, almost 90% were experiencing severe stress and anxiety. So I was able to deliver some real data and some powerful stories about financial struggles. From the beginning, we’ve been both data informed and story informed in our advocacy.

Courtney Robichaud, Liber Ero Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Carleton University and University of Windsor, Deputy Director of Support Our Science: My experience as a grad student was seeing everyone around me essentially living in poverty, and the scholarship and fellowships were all at really low levels of funding. But when I was in meeting with professors and staff members saying “you know, we wish these values could be more, but there’s simply not enough money.” A bunch of professors wrote a letter asking NSERC [Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Canada’s federal research funding agency] for an increase, which kicked off a lot of this. People said that they wanted to hear from grad students and postdocs, and we had data to share, as well as stories about what it’s like trying to live on $23,000 CAD in different parts of Canada- stories that were all different shades of upsetting to hear. People said they didn’t feel worthy or valued, they felt like second class citizens, that they never knew that being a scientist in Canada meant living in poverty. People said they were forced to choose between science and supporting their families, and some left science.

DS: So what changed with the new budget?

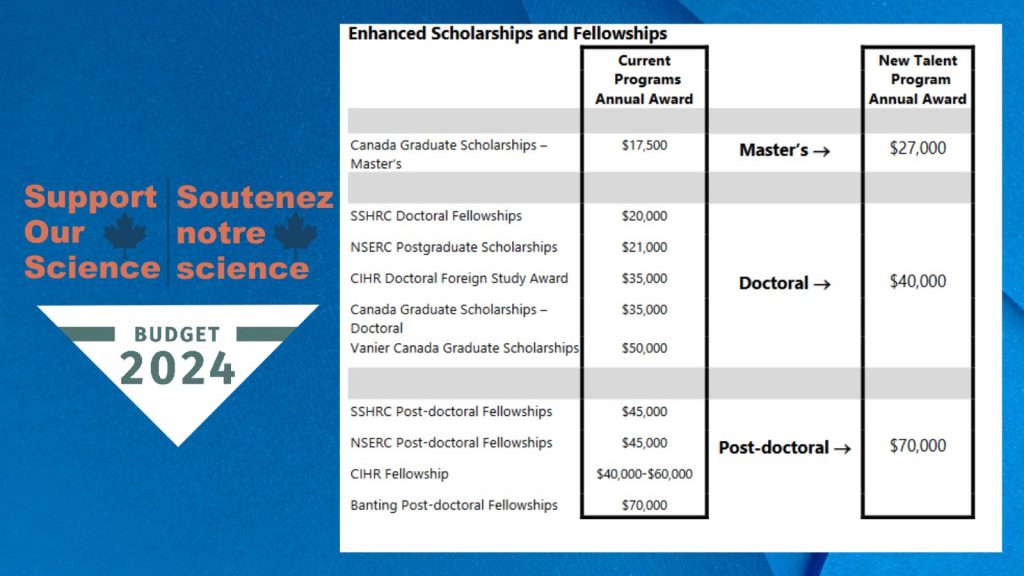

Kaitlin Kharas, Executive Director of Support Our Science and Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Toronto: There are two big changes that happen. The value of awards related to Federally provided scholarships for graduate students and postdoctoral scholars increased substantially. There were many Postdoctoral Fellowships that were at $40,000 CAD a year, that’s not jumped to $70,000. That’s a life altering difference in the amount of money for people, and there were similarly large increases in graduate student scholarships. This is the first time there’s been any increase in 21 years, amazing when you consider how much inflation has happened since 2003. Both the number and the value of Federally funded awards have increased, there’s an additional $1.8 billion CAD going towards these kinds of grants.

Graphic from Support Our Science showing the impacts of their campaign

on graduate student and Postdoc stipends

DS: None of you had done Federal-level policy change advocacy before this. How did you learn how to do this?

Sarah Laframoise: From the beginning, we were always scientists trying to do some advocacy, not advocates talking about science, which wasn’t always successful. And it’s been a long few years of trial and error, and we had to rely on friends and connections in the policy space who were able to give us advice. And since we were grassroots, we didn’t have any funding, everything we were doing was on the side in addition to doing research in our labs. We’d do zoom calls and everyone was in their grad school lab on their lunch break, and we were having big policy conversations like a meeting with the Minister coming up next week. That meeting actually turned out to be one of my favorite meetings I’ve ever had with ap politician, we got an hour with her and just sat there and told her stories about what it’s like being a graduate student or Postdoc. This is probably a tactic that someone in the policy space wouldn’t have taken, but it just felt so real to us, we were unorthodox and a big scrappy but that helped us to be successful. We were always able to be candid and authentic, unlike lobbyists who are paid to advance an argument, we were representing ourselves.

Courtney Robichaud: We also tapped into a great group of people who really did a great job honoring each others’ strengths and finding good roles for each other. Sarah ended up taking a lot of these front facing things while I did a lot of behind the computer behind the scenes stuff helping her to prepare. We also had a laser-focused mandate from the beginning and refused to expand or reduce it as we gained momentum. Eventually we started to change and gain traction and people wanted to join us, which was really interesting to watch.

Kaitlin Kharas: I also think having real grad students and postdocs in the room with us for these conversations was important, and not typical for Canadian advocacy. And for things like the walkout, were able to mobilize grad students and postdocs at such a large scale because they were our peers, that’s maybe something that our advocacy groups couldn’t tap into.

Sarah Laframoise: Yeah I’ll add that when I gave my second testimony to the Standing Committee, I brought 25 grad students and postdocs into the small committee room and I had them all stand behind me during my testimony. I think that was the first time that some of these MPs had ever met a grad student. It showed that we were really paying attention and really care. And we had 3 really successful walkout rallies, but the one in May had 10,000 scientists from 46 institutions participate.

Image from a science walkout rally, courtesy Support our Science

DS: Were senior faculty supportive of this?

Courtney Robichaud: At the very beginning, this was the open letter to NSERC that was led by professors who recognized that 20 years was too long to wait for a raise. And a lot of professors have been supportive and offered help to spread the word, work on drafts with us.

Sarah Laframoise: We’ve been really fortunate to have some really great allies.

DS: But there was some pushback?

Kaitlin Kharas: I think there’s this idea that there’s only a finite size pie, and that if someone gets more money, someone else somewhere might get less. And that’s just not the case. We want to grow the whole pie, we want the whole Canadian research ecosystem to be better, and we want everyone to benefit. We are all on the same team!

Courtney Robichaud: The majority have been supportive, but there are a small minority who say they care about students, but they’ve given us a lot of pushback and grief. Some would say to us things like “ask your supervisor and they’ll explain how funding works,” as if we hadn’t spend years writing reports and policy briefs on that topic. Some have said that if they have to pay their students fairly, they won’t be able to afford to do as much science, which is saying that they don’t care if their people suffer as long as their lab’s productivity doesn’t.

DS: What was it like hearing the good news?

Kaitlin Kharas: There was just an instant sense of relief and giddiness. It was real, it was there, we did it! It was incredibly exciting.

Sarah Laframoise: I called Courtney on my ride home from the budget announcement and was crying in the back of my Uber. This hasn’t changed in 21 years and it changed! This will be a core memory for the rest of my life.

Courtney Robichaud: There was shock that it actually happened. Like, you do something because you believe in it, and you kind of just keep doing it because you’re stubborn. And even if it doesn’t change in one fell swoop you make progress, at least some people know what a postdoc i. But we achieved what we set out to do and it just feels surreal.

DS: What advice would you have for colleagues trying to learn from your success and improve science funding in their countries?

Courtney Robichaud: You’re not alone, build your community and define your system so you can change it. And be stubborn, don’t let anyone tell you to stop. You’re not going to be able to fix everything in one day, and you shouldn’t sit on your hands until you get everything you want.

Sarah Laframoise: As a scientist, it’s so easy to be in a silo and think that what you do and what you know lives and dies in the lab. But be open to the world of policy, because policy influences our lives. Don’t be scared to take these weird opportunities, just take a step out of your silo and try something different.

Kaitlin Kharas: Don’t wait for things to be perfect. You don’t need a professional government relations team, you don’t need to have contacts with everyone. You just need to have a start, and be stubborn, and find the right people, and everything else will come.

Learn more about Support Our Science here.