Ocean plastic is bad news. Last week we were learned that not only did every ocean have its own, personal garbage gyre, but that a huge amount of plastic is “missing” from the ocean–that is, it has been incorporated into the ecosystem in ways we don’t yet understand. While there is plenty of misinformation floating around out there about what exactly these garbage patches are (hint: they aren’t solid islands of trash), there is no doubt that they are effecting the global ocean ecosystem in both profound and subtle ways.

Friend of Southern Fried Science and Deep Sea News writer Miriam Goldstein spent her PhD working on the North Pacific Gyre. Her research has revealed invasive pathogenic ciliates living on plastic trash and plastic-eating barnacles floating in the gyre. She also points out one of the biggest problems with trying to clean up these massive, dispersed “garbage patches”:

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tFSv2eW7g6E

You would almost have to clear-cut the top of the ocean in order to clean up all those little bits of plastic.

There is a sea of theoretical solutions, from dragging nets across the ocean to mooring massive floating arrays, in various states of completeness. Some have been no more than public relation stunts, while others push on despite extensive criticism from oceanographers and other marine experts. Some have promise, other appear to be no more than press releases.

Amid the TED talks, press-pushes, empty promises, and gratuitous publicity stunts, the City of Baltimore quietly built, tested, re-designed, re-built, and deployed a solar-powered, trash-eating, waterwheel-driven garbage scow that’s plying the urban waters of the Chesapeake Bay, pulling tons of trash out of the Inner Harbor every day. Say hello to the Inner Harbor Water Wheel.

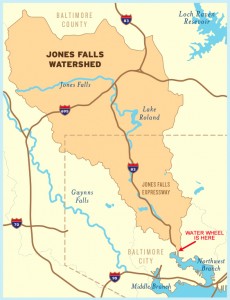

Situated at the mouth of Jones Falls–a major tributary for Baltimore’s Inner Harbor–the Water Wheel’s water wheel is powered by current (and supplemented by solar panels). The wheel drives a series of rakers that pull floating trash out of the Falls and onto a conveyor belt, where it is deposited in a floating dumpster. A bank of booms span the outlet ensure that all trash will be shepherded towards the Water Wheel. The dumpster barge is independent, and can be swapped out as the dumpster fills. The total operating capacity of the Water Wheel is 25 tons of garbage per day.

The Water Wheel is the brainchild of John Kellett of Clearwater Mills, who has been developing the technology since 2008. The first water wheel, which was designed to look like an actual mill house, spent three years in trials, before being removed from the Harbor in 2011 as it couldn’t keep up with the volume of garbage entering the Bay from Baltimore City. The new Wheel debuted this May and, in it’s first major trial, removed 50,000 lbs of trash, ranging from cigarette butts to tires.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=v5l7s6wC50g

So why is the Inner Harbor Water Wheel getting effusive praise from this salty ocean curmudgeon while other ocean clean-up projects have garnered nothing but criticism? Three reasons:

1. Its footprint is tiny, its reach is huge. Other ocean cleaning arrays rely on stretching massive booms across the ocean, exposing them to wind, potentially entangling marine animals, and requiring huge resource investments. Others must travel, burning fossil fuels and pulling large nets that collect both plastic and marine life.

By positioning it at the mouth of a major river, the Water Wheel can capture the entire Jones Falls watershed with a single short length of boom. The Jones Falls watershed encompasses 58 square miles of densely populated city. All drains lead to the sea, and all drains in this watershed lead directly to the Water Wheel.

2. Visibility matters. Most proposed ocean clean up solutions are out of sight and out of mind. A floating platform moored thousands of mile offshore does little to inform the public about the consequences of plastic waste. In contrast, the Water Wheel is moored in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, one of the most heavily traffic locations in the state. Within a few hundred yards are five-star restaurants, the National Aquarium, major financial offices, and dozens of tourist attractions.

There’s nothing hidden about the Water Wheel. Passersby are treated to the very visible (and, frankly, quite attractive) machine and can see exactly how much garbage has been pulled out of the water that day. This is more important than you might think, because, beyond clean-up schemes, the real solution to reducing trash in our ocean is to stop putting trash in our ocean.

3. Solutions begin at the cradle, not the grave. Here’s the real problem with going out to the middle of a garbage gyre and scrubbing it clean: the damage is already done. By the time most plastic waste reaches the gyres, it’s heavily degraded, broken into tiny pieces and worn away by the sea and the sun. Photodegraded particulate plastic, the last phase of ocean plastic and the great bulk of the garbage patch, has already leached most of its chemicals into the sea. Attacking the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is treating the symptoms, not the cancer.

The Water Wheel catches plastic and other trash at the source, before it has a chance to reach the ocean, before it becomes part of the North Atlantic Garbage Patch. This matters. A recent study in PNAS revealed that we don’t even know where most oceanic plastic goes. So no matter how efficient the high seas-based clean-up array, it will never collect more than a tiny fraction of the total trash in our oceans. Meanwhile, the Water Wheel keeps spinning, keeping that same trash from reaching the sea.

The Water Wheel may not be the perfect solution for every situation, but where it can work, it’s hard to argue against using using it. Major cites with tightly controlled tributaries are the perfect candidates for this technology. I’ve seen a lot of fantastical ocean clean-up proposals in the last half decade, and this is the first one that I’m genuinely excited about.

The Inner Harbor Water Wheel is supported by Baltimore’s Healthy Harbor Initiative, and is part of the plan to make the Inner Harbor swimmable by 2020.

I think this is a brilliant idea and would be nice to see on all rivers. How do the boats get through the booms?

“How do the boats get through the booms?”

In this case, they don’t. The Jones Falls isn’t a navigable waterway.

brilliant!