Back in the day, I worked as an intern at Rhode Island Marine Fisheries, where my job was basically to provide general field work help with whatever survey needed an extra pair of hands (yes, it was an awesome job). One of these was a beach seining survey looking at juvenile fishes using Rhode Island’s coastal salt ponds as nursery habitat. Among the usual silversides, mummichogs, and juvenile flounder, two of the ponds were also home to entire schools of something that I was only familiar with due to having relatives in Virginia: spot. These little Scianids, a member of the same family as Atlantic croaker and red drum, are caught in droves in the waters of Virginia and the Carolinas but traditionally have been rare north of the Chesapeake Bay. They were one of the more common species we caught in these two Rhode Island salt ponds, and occurred so consistently that we could actually observe them growing over the course of the summer. It isn’t unheard of for stray tropical fishes to get swept into Narragansett Bay on Gulf Stream eddies, where they’re either collected by aquarists or die during their first winter. However, these were populations of spot that we were seeing. I don’t know if these fish survived their first winter or have come back since I moved down to North Carolina, but even at the very beginning of my interest in fisheries ecology I knew this was odd.

Fast forward a few years and I was working on a shark-tagging trip off of Cape Hatteras in February. Among the usual winter species like sandbar and dusky sharks, the commercial fisherman we were working with pulled up something unusual: a six-foot scalloped hammerhead. This is not a species one typically associates with winter waters, and certainly isn’t common off of North Carolina in February. Labmates of mine have caught juvenile bull sharks in the same survey during winter months. The anecdotes don’t end with me and people I know. Species as diverse as seahorses and ocean sunfish are crossing north of Cape Cod and becoming common in the Gulf of Maine. In the same region lobster fisheries are collapsing south of Cape Cod while record numbers are being caught in Maine and Canadian waters. On the other side of the Atlantic, herring seem to be leaving mainland European waters for Iceland and the Faroes. All of this points to a widespread trend of northern range shift among marine species. This range shift is already having consequences for humans: Maine lobster prices have plummeted from the sheer number of lobsters being landed and conflicts over the European herring quota have lead to serious talk of European Union trade sanctions against the Faroese.

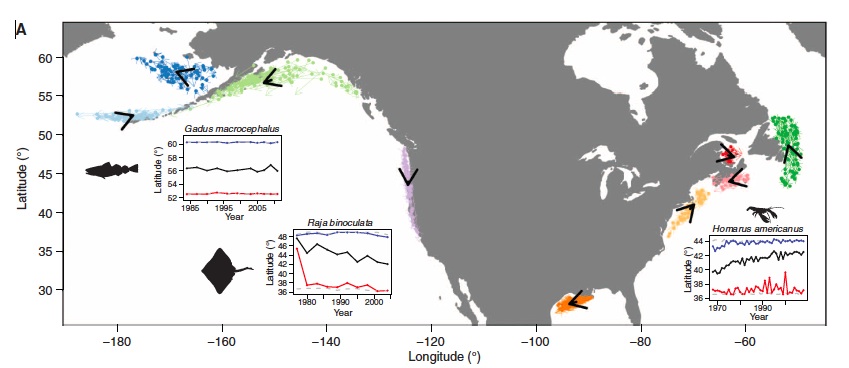

The main driver of these range shifts is, sure enough, climate change. However, sea surface temperature in and of itself isn’t necessarily the best predictor of shifts in species distribution. What really matters, according to a recent paper by Pinksy et al. (2013), is what is referred to as “climate velocity,” or the speed and direction of climate shifts. By looking at expansive trawl survey data sets that encompass 360 species throughout U.S. and Canadian waters, the researchers found that local assemblages of species followed climate velocity very closely and consistently, and that this variable was a better predictor of range shifts than fishing pressure, survey methods, or even the species’ own individual biology. Basically, Pinksy et al. found that entire marine communities shifted with the speed and direction of climate change. However, not all communities shifted north: some moved south, some moved around landforms, and some moved to deeper water. This is because local climate velocity is not just a function of sea temperature, but also local currents and geography. For example, colder conditions (and the species that inhabit them) shifted south in Scotian Shelf region, following cold fresh water released by melting polar ice. This was especially pronounced in the Gulf of Mexico where there really isn’t much “north” to shift to, so species shifted to deeper water in response to warming temperatures.

This is a big deal, because according to their latest report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is 95% confident that we’ve done this to ourselves. Through climate change we have essentially pushed marine species ranges around, and we may not be entirely happy with where they’ve ended up. These changes may mean expanded ranges for warm-temperate and tropical species, but economically-valuable cold-ranging species like lobster, cod, and winter flounder can only shift so far north before they hit the poles and nowhere left to go. All the while they’ll be crossing into new regions and across state and international borders. As lobster catches skyrocket in Maine and maritime Canada, Massachusetts and Rhode Island fishermen may find themselves switching from flounder to croaker. What will you miss or look forward to seeing on the end of your fishing line?

References

Pinsky, Malin L., Worm, Boris, Fogarty, Michael J., Sarmiento, Jorge L., & Levin, Simon A. (2013). Marine Taxa Track Local Climate Velocities Science, 341, 1239-1242 DOI: 10.1126/science.1239352

It gets more complicated as you factor in other habitat factors besides temperature, at least for the cold water species that are retreating. While not all fish have them, many fish have specific topographical habitat affinities or biological community needs that are not necessarily evenly distributed within the regions where the temperature has changed. For some species this could (will?) lead to range/population fragmentation and local extinctions. (e.g. http://icesjms.oxfordjournals.org/content/69/10/1753.abstract )

Chuck,

Nice post. Please also check out this item on how fishermen and scientists are wrestling with ocean warming impacts in New England. http://www.talkingfish.org/newengland-fisheries/managing-fisheries-in-%e2%80%9ca-climate-of-change%e2%80%9d

Our friends at Island Institute organized an event over the summer to have people share observations and thoughts on adaptation. Sea surface temps in New England last year broke the instrument record going back 150+ years (the attached link has an amazing animated map of temperature anomalies). People are definitely seeing the effects as species shift. And some emerging science links warming to reduced productivity in the food chain, seabird deaths due to lack of forage, and more. I don’t think you’d find many climate change deniers on the waterfront here anymore. They can see it.

Thanks

Jeff