2023 felt like a year where I was just treading water. I barreled through it so fast that I barely registered everything that we accomplishes (and just how much is left to finish). This was a kludge year for me, with lots of small projects instead of one, big, overarching project.

Onwards!

Deep-sea Mining remains Schrodinger’s Industry

The beginning of 2023 saw the end of my four year tenure as the Editor-in-Chief of the Deep-sea Mining Observer (despite a few conspiracy heads looking for gossip, there’s no drama here. The project was funded for a set period of time, I managed to convince the funders to keep it running for an additional 2 years during the pandemic, but there was always a sunset plan in place). I loved running the DSMO, but by the end I was well and truly burnt out. Producing 4 to 5 feature length articles on deep-sea mining every month forced me to dig deep into the full breadth of the industry, but by the final year, I knew I was ready for something else.

This was a year in big changes and slow movement in the development of deep-sea mining, leading up to what promises to be a dramatic negotiation in summer 2024. Unfortunately, I won’t be there, as the Secretariate of the International Seabed Authority has adopted an adversarial stance towards journalism and independent reporting, which was rippled through the media landscape. Deep-sea mining remains very much Schrodinger’s Industry, existing in a superposition somewhere between inevitable and impossible at scale. I remained involved in deep-sea mining through other avenues, contributing to working groups and advising other NGOs and UN bodies.

My final act as editor before closing up shop was to sign on to the scientist call for moratorium on the development of the industry, a move which I explained in more detail here: One Mining Code to Rule Them All: The poison pill at the heart of the Deep-Sea Mining negotiations.

Drink Rum, Save the Ocean

We built a distillery. In 2019, Jake Levenson led a team of ocean champions from Oceans Forward and DomSetCo to explore a radical new idea in ocean conservation. What if, instead of partnering with commercial enterprise to receive some small portion of temporary funding from profits, a conservation NGO owner the commercial enterprise? The Rosalie Conservation Center, a conservation training center, fish hatchery, and run distillery was born.

It was an idea. Then it was a building. And finally, in the last days of 2023, the first bottles of rum were filled. It’ll be a little while still before Sperm Whale Reserve, Rosalie Bay Distillery’s first run, named in honor of Dominica creating the world’s first marine protected area for Sperm Whales, makes it stateside, but if you happen to be in the Commonwealth of Dominica, go try our rum.

I only played a small part in a much bigger project here, working with Jake to complete the environmental impact assessment and playing the role that I always play in big, complex, logistical problems, being a fixer for ocean conservation groups, standing by to tackle the weird, novel challenges no one can anticipate. I did have the rare opportunity to merge ocean conservation and woodworking, handcrafting a lovely little dovetail box for the bottle of rum to be delivered to one very important VIP.

The Chesapeake Bay, Electrified

The other half of the deep-sea mining debate is the question: if we aren’t going to get critical minerals from the seabed, how are we going to build enough batteries to power the green revolution? This year we kicked of the next phase of our NOAA SeaGrant sediment microbial batteries project, harnessing the reduction potential of benthic muds beneath oyster aquaculture facilities to generate low-voltage power while reducing sulfates and other pollutants in the Chesapeake Bay. The first set of batteries have been deployed and we’re working on lab-base modules to. And yes, you can charge you cell phone with them (just very, very slowly).

And, of course, because the beauty of conservation technology is adaptability, we use a heavily modified OpenCTD to measure current in the batteries.

I am fully aware of the irony in saying that instead of getting battery metals form the seafloor, we can make seafloor batteries. Sediment microbial batteries aren’t so much a power source as a way to clean up the Bay, but it was my work in deep-sea mining that got me thinking about batteries and what we really need when we talk about power.

Microplastics in the Deep Sea

I started something entirely new. In 2023, I inherited a massive archiver of biological samples from my PhD advisor. These samples include organisms from deep-se hydrothermal vents around the world, methane seeps, and the vast abyssal planes. Many of the most pristine samples were put on display the the St. Michaels Library, in St. Michaels Maryland, where they will remain until… tomorrow. We’re looking for the next home for the deep-sea mini-museum this Spring (we already have sites lined up, so no, this isn’t a call for offers to host).

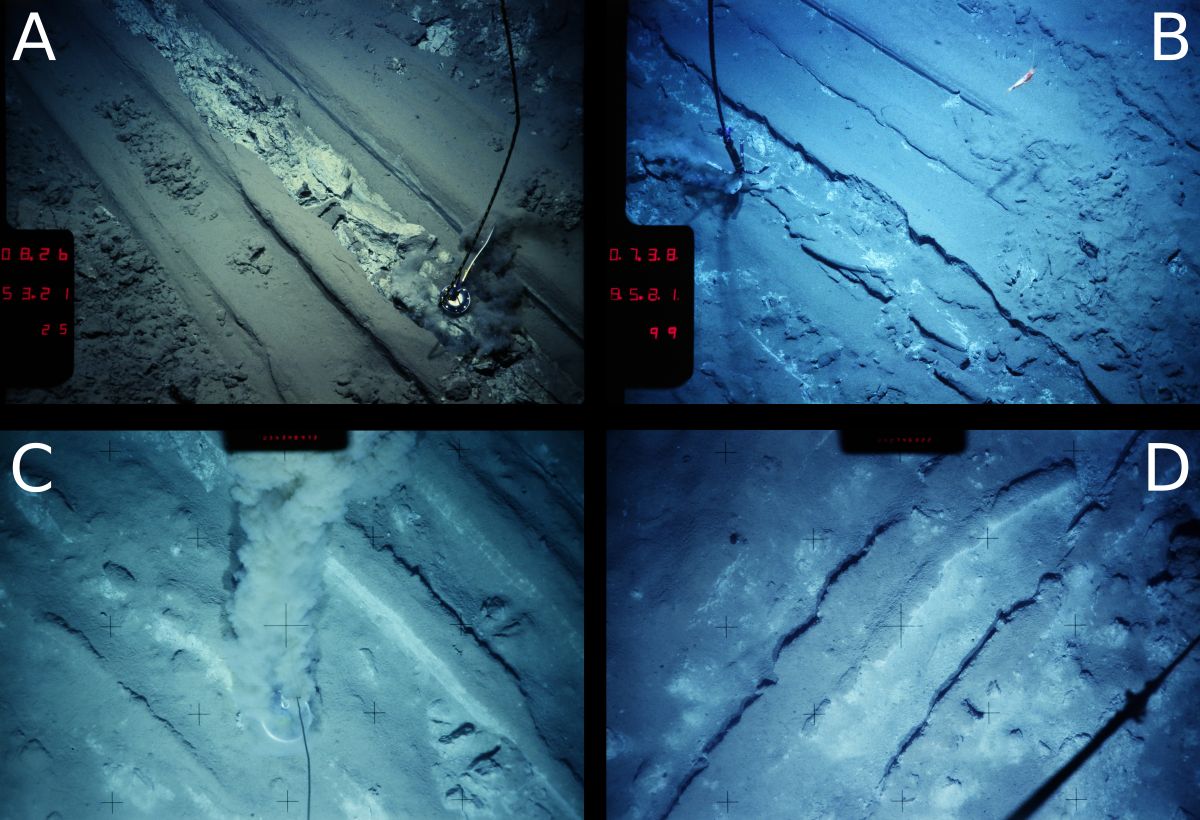

With these samples, we kicked off the first global survey of microplastic accumulation in the tissue of animals from deep-sea hydrothermal vents and other deep-sea ecosystems. The preliminary results are not comforting. At the world’s deepest known hydrothermal vents, in the Mid-Cayman Spreading Center, we’re already seeing plastic in large volumes within the tissues of deep-sea shrimp and snails. These are ecosystems that we only just discovered a decade and a half ago, and they’re already loaded with plastic.

The Year of the OpenCTD

2023 was supposed to be the year of the OpenCTD. One of my reasons for bringing the Deep-sea Mining Observer to a close and not pursuing deep-sea mining work for the year was so that I could focus on refining the OpenCTD. Funding challenges got in the way of that, forcing me to shift my priorities to other projects. But that doesn’t mean things stopped. Thanks to ongoing support from Patreon, we were able to continue work on the OpenCTD project regardless of the unpredictability of current funding contracts.

There have been a few huge advancements in the development of the OpenCTD, the first being that we received small grant from the Open Science Hardware Foundation to run a documentation workshop with the goal of updating all the OpenCTD documentation and improving the workflow for students and educators. Over the course of a week, a small team of students, professional educators, and hardware developers built a trio of CTDs, which we calibrated and deployed in the Miles River.

The end result of that workshop was the publication of OpenCTD: Construction and Operation, fourth edition, the most comprehensive and clear guide to building your own CTD, ever. We also further refined the calibration process and released a manual just on the calibration of the OpenCTD, for those who already have a unit.

And the biggest news is that, ten years after we launched this project, right here on Southern Fried Science, we have a peer-reviewed paper, with extensive data validation, in press and due to publish early in 2024.

Thankfully, our funding for 2024 is secured, which means that, though a year later than I would have liked, this will be the Year of the OpenCTD.

Southern Fried Science is free and ad-free. Southern Fried Science and the OpenCTD project are supported by funding from our Patreon Subscribers. If you value these resources, please consider contributing a few dollars to help keep the servers running and the coffee flowing. We have stickers.