It’s generally thought that baleen whales are too large to be successfully attacked by most marine predators. Orcas are typically considered the only real predatory threat to large whales, and even they have to use teamwork to take down a young whale. Large sharks, which also sit near the top of the marine food web, are known to scavenge on whale carcasses as a nutritious and blubbery supplement to their usual diet of fishes and smaller marine mammals. However, evidence has been found that white sharks actually take a proactive approach to increasing the whale carcass supply by attacking live northern right whale calves. Now researchers in South Africa directly observed dusky sharks actively teaming up to bring down a humpback whale calf.

Dusky sharks are known for being one of the largest species in the Carcharhinus genus and their populations have the dubious honor of being among of the most depleted. Being big sharks, they function as apex predators and are classified as “occasional predators” of smaller whales thanks to the remains of dolphins and other marine mammals found in their stomachs. There have been no direct observations of this species attacking any cetacean and these sharks were thought to live a solitary lifestyle feeding on fish, other sharks, and the occasional dolphin.

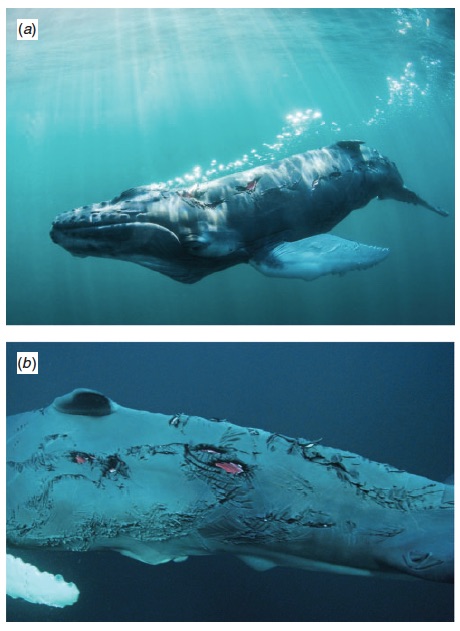

The attack reported by Dicken et al. (2014) was observed by researchers and divers checking out South Africa’s annual sardine run, a marine predator party that has been featured in many nature documentaries. They found a lone humpback whale calf being followed by a group of 10-20 adult-sized (2-3 m/6-10 ft) dusky sharks. The whale was covered in superficial shark bites, and individual sharks were observed (and apparently filmed) charging at the whale and taking bites out of its left side. The attack went on for 6.5 hours after being first observed, when the whale finally dove and did not surface for an hour. At this point it was assumed the whale had finally died of its injuries or exhaustion.

This observation has a lot of interesting implications. The most obvious is that it can’t be taken for granted that whales are protected from shark predation by size alone. The dusky shark is an apex predatory species, but is physically similar to many other large Carcharhinid sharks. If duskies can take down a humpback whale calf, then other large sharks like bull sharks, tiger sharks, and oceanic whitetips may also be physically capable of threatening large baleen whales. Sharks may be an important part of whale ecology.

Perhaps more interestingly, this is a case of a normally solitary shark working cooperatively to take down large prey. A single humpback whale calf is far too big a meal for a single dusky shark, so there is clearly a shared benefit to all the members of the pack. The idea of sharks forming packs isn’t that far-fetched: cooperative hunting has been observed in other shark species and shark social behavior has proven to be much more complex than previously thought. Dusky sharks normally keep to themselves but do gather in large numbers during the sardine run. Did this group form incidentally or is this something dusky sharks do on a regular basis? As dusky shark populations rebuild, will we start seeing this sort of thing more often?

If nothing else, this gives me more ammunition the next time I get into a “my study organism can beat yours up” conversation. Yes, ecologists have those. Often.

Reference

Dicken, M. L., A. A. Kock, and M. Hardenburg. 2014. First observations of dusky sharks (Carcharhinus obscurus) attacking a humpback whale (Megaptera novaengliae) calf. Marine and Freshwater Research. http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/MF14317

Have to say that I’m extremely dubious of the report here. While an interesting observation, one can plainly see that it was a solitary humpback calf and more than extremely emaciated. This whale calf is so skinny that it was likely in the process of dying already. Scavenging immediately prior to something being actually deceased does not make it a predatory event. I have no doubt that dusky sharks could not contend with a healthy whale (even a calf).

I have to expect this is one of those events so rare to be considered almost unique. A calf may lack the experience/knowledge to defend itself, surely this one had even less opportunity having been starving for an extremely long time. The images tell the story. I would chalk it up to individual sharks taking a chance on a wounded “windfall” meal and cannot be considered group tactics by the sharks. The fact that that the bites were almost entirely concentrated to the left posterior region also likely indicated an area that may have been wounded prior to the sharks attention.

Any assumptions as to a concerted, “cooperative” attack strategy is entirely face-based and completely without precedent. At best its a superficial preliminary observation, at worst its a gross misunderstanding of the circumstances. The fact that the whale’s overall condition was ignored (whale calf alone and severely emaciated) indicates a poor translation of the events that transpired.

I hope someone consulted a cetacean biologist prior to the write up. The obvious bony protrusions along the whale’s form indicate an extremely unhealthy individual. There is no mention of the whale calf’s conditions (solitary and emaciated) in the abstract, but perhaps it is addressed in the article. I would also caution against assuming cooperative feeding strategies from sharks not known for these behaviors. “Cooperative” implies a strict social structure and not a matter of convenience; much like vultures on a dying zebra. The fact that they take a few pokes at the zebra at similar times does not implicate cooperation.

I appreciate the write up here by Mr. Bangley, but it seems obvious to me the paper and the incident are being taken a little too liberally (in my opinion). Boiled down – a solitary, starving whale calf near death was being followed by a group of opportunistic dusky sharks looking for an easy meal. This (again, in my opinion) does not imply regular whale predations by small shark species. Its more likely a peri-mortem scavenging event.

I showed this article to a couple whale experts. They agree the whale is not healthy. Although I would have to agree with Sean on the technical terms of predation vs. scavaging, I would tend to agree with Drew overall on the key points he brought up. This story seems very similar to the whole “Orca’s put GWs into TI” story that occurred. You have some people witness something, some researchers experienced in one field but not in another probably made loose theories and it runs amuck as a “new discovery” when the media gets a hold of it. Vultures have been witnessed coming together and actively feeding on an animal while it is still alive, Komodo Dragons do the same. If we go off of this theory then piranhas are “cooperative hunters” as well which everyone knows is not true either. This seems to me to be another case of a media writer making implications that they aren’t qualified to make in order for their story to make headlines.

Thanks for some interesting counterpoints. Honestly, I find the whale’s side of the interaction the less interesting side, though I definitely appreciate input from people with more familiarity with mysticetes. Group formation in and of itself is fairly rare for dusky sharks, let alone group formation to feed on a whale that isn’t dead yet. The fact that this sort of behavior is unprecedented for dusky sharks, even if it involves a whale with one fluke already in the grave, is what made me interested in writing up this paper.

I agree that this is likely an extremely rare (though extremely interesting) event and that the calf was clearly not enjoying most of the advantages that a humpback whale would normally have in this situation. That said, the authors termed it a predatory interaction and there have been other published observations of large sharks making predatory attacks on newborn or young-of-year whales. The white shark reference I linked to in the article included reports of bite scarring on living juvenile North Atlantic right whales, suggesting the sharks attacked whales that were healthy enough (or had a parent nearby) to survive the attack. Dusky sharks aren’t white sharks, but adults of this species will feed on large-bodied prey like other sharks and dolphins, and may be capable of overpowering a lone, malnourised, and possibly previously-injured whale calf if they engage as a group.

Shark cognition isn’t well-understood but there is already evidence that social behavior among sharks can be complex. Telemetry studies have shown that reef sharks (in the same genus as dusky sharks) and catsharks will preferentially associate with the same individuals. Sand tiger and broadnose sevengill sharks have been documented forming groups and systematically attacking prey. Fishermen swear that spiny dogfish will attack in groups and dismember fish larger than themselves (I’ve seen evidence of this firsthand going through dogfish stomach contents). I’ll admit the idea of cooperatively-hunting dusky sharks is a bit of fun speculation on my part (and I had thought pretty clearly written as such), but based on my own experience researching predator-prey interactions involving sharks it doesn’t seem completely implausible (when not posting here I’m working on a PhD focusing on shark habitat use and possible links to predatory/competitive interactions).