The 2010 Shark Conservation Act prohibits removal of fins at sea for all sharks landed in U.S. Waters, with a glaring exception for smooth dogfish, or smoothhound sharks. In an effort to ensure that fishermen aren’t performing the cruel practice of throwing a still-living but finless shark overboard, a fin:body ratio of 12% for smooth dogfish became law as part of this bill. This means that the total weight of smooth dogfish fins cannot be more than 12% of the total dressed weight of the bodies when the sharks are landed.

Some time ago I wrote a post questioning where this 12% ratio came from, especially since the best available published literature at the time suggested a ratio of only 3.5% for smooth dogfish. The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Management Commission (ASMFC) responded, claiming that they had data backing up a find:body weight ratio of 7-12%. Now, thanks to the SEDAR stock assessment workshop for this species, the study conducted by the ASMFC is publicly available (albeit nearly four years after it was written into the law).

So where does this seemingly extremely high fin:body ratio come from? It depends on how you slice it.

Why is the ratio of fins to body weight such a big deal? Smooth dogfish are the only species exempted from having to be landed with fins attached under U.S. fishery management policies (with the exception of some states that currently, but perhaps not for much longer, allow fin removal for spiny dogfish in their waters). All other sharks must be landed intact with fins still attached to aid in species identification back at the dock. Because the exception for smooth dogfish potentially creates a huge loophole in what is otherwise one of the strongest shark conservation laws anywhere, it’s crucial to get the fin:body weight ratio right. If it’s too high, it becomes easy to sneak extra fins in with the smooth dogfish fins, and may even open up a black market for fins from other species that can be passed off as smooth dogfish. On the other hand, if the ratio is too low then fishermen may need to land fewer fins than they have sharks for, creating waste in the fishery and possibly getting fishermen trying to avoid that waste into legal trouble.

To try and find the ideal fin:body weight ratio, Hawk et al. (2014) consulted commercial fishermen in New Jersey and North Carolina (the two states landing the most smooth dogfish) on their typical practices for processing smooth dogfish at sea. They then took a sample of 77 sharks between the two states, removed the fins and dressed the sharks using the same methods used in the fishery, and compared the combined weight of the fins with the remainder of the body.

As mentioned in the previous post, there’s an important distinction between whole weight and dressed weight. Whole weight is the weight of the entire shark, while dressed weight is the weight of the shark carcass after the fins, head, and internal organs have been removed. Suffice to say, dressed weight is quite a bit lower than whole weight. Fishermen generally land smooth dogfish as detached fins and finless, headless “logs,” so a fin:body weight ratio involving dressed weight represents the state that these sharks are in when they show up at the fish house.

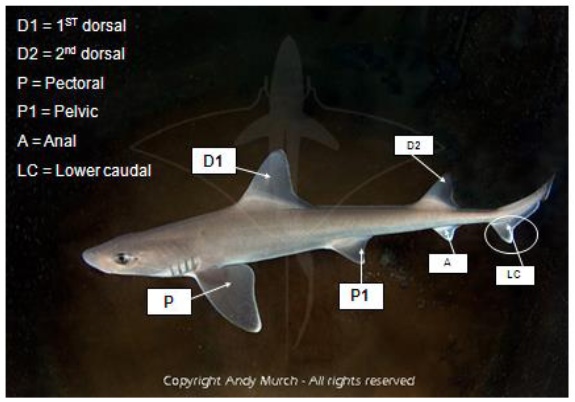

Interestingly, the fins removed are not necessarily the same ones removed in other studies on shark fin:body weight ratios. In consulting with fishermen, Hawk et al. (2014) found that fishermen actually remove the caudal fin (tail) along with the dorsal and pectoral fins. This is surprising because the tail contains a lot of muscle and vertebral cartilage, which adds a considerable amount of weight to the fin side of the ratio. One wouldn’t think there would be much fin material in the caudal fin, especially for a shark with as scrawny a tail as a smooth dogfish, but apparently there is a market for this fin as well.

All told, the fin:dressed weight ratio in smooth dogfish can range from 7.76% (if the caudal fin is not included) to 13.94% (including the caudal fin). If fishermen truly are selling the caudal fins, then the 12% ratio pushed into the 2010 Shark Conservation Act is actually relatively conservative for the species.

While allowing fin removal of one particular species does still present the opportunity to swap in the fins of other species, it’s good to know that the 12% fin:body weight ratio wasn’t just pulled out of thin air. That said, it seems like it would still have been easier to just have the fins-attached rule apply to all shark species. This will undoubtedly be something the National Marine Fisheries Service will have to address as they move forward with the smooth dogfish fishery management plan.

References

Hawk, M., R. Babb, and H. White. 2014. Smooth dogfish (Mustelus canis) fin-to-carcass ratio project. SEDAR 39-RD-04.

Update – 08/09/14

Everyone should read the first comment below by Sonja Fordham, who has been following dogfish fishery management better than anyone in the conservation community. She correctly points out that there is a distinction between finning (which specifically involves keeping only the fins and throwing the rest of the shark overboard) and removing fins at sea while still keeping the rest of the shark. Some of the above text has been edited to reflect that distinction. Also, if you’re not happy with the exception from the fins-attached requirement for the smooth dogfish fishery, NMFS is in the process of developing a fishery management plan for the species and public comments can be submitted before November 14th. Also, the ASMFC is planning to enforce a fins-attached rule for spiny dogfish fisheries (because spiny dogs are in fact a shark and not specifically exempted from any fins-attached fules), and public comments are open for that too. As always, keep civil and make sure you leave a well-informed comment that those making the final decision can actually use.

“Finning” (slicing off a shark’s fins and discarding the body at sea) is illegal throughout the US (not “allowed” anywhere in this country). Removing the fins while retaining the body is not usually called “finning” but considered more like “processing” at sea, which is currently allowed under some Atlantic state regulations for smooth and/or spiny dogfish. Federal regulations ban removal of fins at sea, but shark heads CAN be removed. NMFS does not allow at sea fin removal for spiny dogfish anymore and has just this week issued various proposals for how to address the Shark Conservation Act smoothhound exception in federal regulations (not yet final, 12% not yet allowed by NMFS). The study that found 12% is near the upper range of smoothhound ratios was conducted YEARS AFTER Congress put 12% smoothhound exception in the Shark Conservation Act, and was reviewed by the ASMFC Technical Team AFTER adoption by the ASMFC (not good or standard form). The Spanish have shown us that there are plenty of ways to vary fin cutting techniques that can yield high ratios. The higher the ratio, the more wiggle room there is for undetected finning. The ASMFC Law Enforcement Committee in February filed a unanimous report stating that fin-to-carcass ratios were not enforceable. Both the ASMFC and NMFS are now accepting comments on options to eliminate exceptions and require that all sharks are landed with their fins still naturally attached. Comments from scientists and other concerned citizens are encouraged.