A press release circulating on Twitter, which claims that a “deadly expansion” of a California fishery will negatively affect critically endangered leatherback sea turtles, has been making waves in the marine conservation and fisheries communities, inspiring a series of interesting discussions. Is it better to buy US-caught seafood with some bycatch than foreign-caught seafood from fleets with less strict environmental regulations? Is the current “Pacific leatherback conservation area”, a large region of the ocean where no fishing is allowed, too much of a restriction on U.S. fisheries? Can there be a balance between fisheries and conservation? I invited Jonathan Gonzalez, a California graphic designer with a strong interest in marine conservation issues, to write a guest post about the swordfish fishery in question. You can follow him on Twitter here, and he’s happy to answer your questions about this issue in the comments section of this post. In addition to his graphic design work, Jonathan has served as the assistant director of the Santa Barbara Marine Mammal center, and has worked with the California Shark Coalition to gather support from fishermen for the state’s recent ban on shark fins.

by Jonathan Gonzalez

Fisheries are complicated and often misunderstood. We often see conflicting information about what fish we should or should not eat and we see general statements about certain gear types that over simplify an extremely complex issue. But don’t be discouraged, learning about fisheries can be very fun and can lead to eating seafood with confidence, free of any guilt or confusion. One particular fishery I want to talk about that is not only complicated, but in my opinion it is California’s most misunderstood fishery. I’m talking about the drift gillnet (DGN) fishery for swordfish and common thresher sharks (CTS). Swordfish, CTS and mako sharks caught in Hawaiian set longlines are also landed in California, but I am not going to talk about that here. I am going to focus on the DGN fishery because this fishery has been in the headlines a bit lately because of recent motions that were voted on at a Pacific Fisheries Management Council (PFMC) meeting. Here is a press release you may have seen that in my opinion is full of factual errors and a few downright slanderous statements. I’m not going to point them all out and I’m not going to try to tell you what to do. Instead I am going to give you some background about the fishery and provide you with information that will hopefully help you to make an informed decision for yourself. Most folks prefer things to be simple. Most consumers like the idea of having a handy pocket guide that helps them to make the right choice when purchasing seafood. This can be a good thing because I actually believe that when we are presented with a clear choice between right and wrong, we have a pretty good track record of doing the right thing. These guides can also be bad because although they are created with good intentions, they lack up to date information on every fishery because let’s face it, we just don’t know enough about them all yet. We live in a time where a lot of people concerned about the state of the world’s oceans and they are willing to do something about it. That combined with the internet and social media, all of a sudden anyone with a computer is connected to a ton of information about what fish is “sustainable” and what gear types are bad. This is very exciting, but at the same time it’s pretty scary. I say scary because sometimes campaigns created by folks with good intentions can have negative transfer effects that can do more bad than good to their cause. I’ll come back to that.

It would be great if fisheries, fisheries management and seafood market chains were simple, but they’re not. Some are extremely well managed, some are illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU), and everything in between. Sometimes it seems the more you learn about fisheries, the more you realize you don’t know. It’s a bit overwhelming (or extremely interesting) to attempt to wrap your head around everything involved in a single fishery, let alone several of them. I try to keep it simple by supporting fisheries that I know are well managed, and not supporting fisheries that either I know are not or I’m not sure about. Pacific swordfish have been harpooned since around the turn of the 20th century, but landings always varied year-to-year due to oceanic cycles in which the swords did not surface during the day. Swordfish generally surface at night to feed and swim to the depths during the day, though under certain conditions they will surface or “fin” during the day.

In 1978 a group of fishermen experimenting with DGN targeting CTS discovered that large-mesh nets set at night could catch swordfish, too. After biological studies were done on the gear, the California DGN fishery for swordfish started in 1982 following a bill that passed allowing fishermen to target swordfish with short-length, large-mesh gillnets. The primary target is swordfish, but CTS and shortfin mako sharks are also taken in the fishery. 200 permits were issued to this new, limited access fishery. Since then it seems like it has been one restriction after the another, mostly because the areas they fished were also home to several species of protected marine mammals and sea turtles, a migration route for gray whales and also a nursery and pupping area for CTS and other sharks. The Southern California Bight is a major pupping area and generally considered a nursery area for several species of immature sharks. A closure of the DGN fishery was implemented in 1986 from May 1- August 15 within 75 miles of the California coast creating an enormous conservation zone for CTS, shortfin mako and other shark pups and juveniles. In 1985 a closure to the fishery was implemented from December 15- January 31 within 25 miles of the coast to protect whales, mainly migrating gray whales. In 1990 voters approved Prop 132, which removed gillnets from state waters (within 3 miles of coast) mostly in order to avoid interaction with pinipeds. In 2001, the Pacific Leatherback Conservation Area (PLCA) was implemented to protect leatherback and loggerhead sea turtles that come here to feed on jellyfish. This is a 230,000 square mile area that starts at Point Sur and out to the EEZ (200 miles offshore) all the way up to the Northern Oregon border. The PLCA is off limits to DGN fishing from August 15- November 15. When the PLCA reopens, the weather is typically too bad to fish anyway, creating serious safety-at-sea issues for the ones who decide to tough it out. One transfer effect of the PLCA was that most DGN fishermen that lived within the coastal range of the PLCA were forced to exit the fishery completely.

California’s swordfish fishery has a small impact on Pacific swordfish stocks, yet California fishermen are the most strictly regulated of all Pacific Rim fleets. When you take weather and all the above restrictions into account, one could say for all intensive purposes it is a year round ban. Perhaps that is one of the reasons why there are only around 32 active vessels in the fishery today compared to 129 in 1990. Barlow and Cameron (2003) reported that acoustic pingers significantly reduced cetacean and pinniped bycatch in the DGN for swordfish and CTS in California during a controlled experiment in 1996 and 1997. In 1997 electronic pingers and 6 fathom extenders were mandatory on all DGN sets. Pingers are acoustic deterrent devices which, when immersed in water, broadcast sound with a 4 second pulse rate. They are required to be attached every 300 ft. and within 30 ft. of the floatline. Though they drastically increase the time for fishermen to set and pull the nets in, pingers have lowered bycatch of cetaceans by 50%. The 6 fathom extenders (buoy lines) have drastically reduced bycatch of California sea lions and CTS which are typically near the surface at night when the nets are being dragged. Currently, over 90% of the total bycatch by numbers in the DGN fishery comes from a single species, the common mola (sunfish). Although there has not been a definitive study on the survivorship of common mola released from DGN gear, observations by NMFS observers and researchers suggest that a high percent (>90%) of them are released alive. This is where it gets even a little more complicated. While restrictions and closures piled up and landings and efforts decreased over the years, the U.S. continues to consume more swordfish than any other country. As a result, most swordfish consumed here in the U.S. is imported from foreign fleets that have no regulations to protect turtles and sharks to say the least. Most of this comes from areas where leatherbacks are considered more vulnerable than here on the West coast of the U.S. This undermines the important efforts that U.S. fisheries biologists and fishermen have made to protect such species.

Unilateral conservation regulation of U.S. fisheries can lead to higher sea turtle bycatch rates off shore. I like to call this the “leaf blower effect.” This also presents an uneven playing field to our local fishermen who simply can’t compete with the cheap prices of imported seafood. So how can we increase landings of swordfish in California without going backwards on management efforts to protect vulnerable and or endangered species? Fortunately this is what was discussed at the PFMC meetings on March 3rd. Topics discussed included a motion to determine if any changes could be made to the southern boundary of the PLCA to enhance DGN fishing opportunities. If the data and analysis show that there is any flexibility, then NMFS Protected Resources and Sustainable Fisheries divisions will determine any next steps. Another motion that came up was to have NMFS report to PFMC at their meeting in March 2013 with progress of research evaluating the bycatch rates, catch per unit effort, and other useful information of other gear types targeting swordfish, which could be used as an alternative gear to DGN to catch swordfish. In my opinion, this is great management at work. The World Wildlife Fund, The Nature Conservancy and the Long Beach Aquarium of the Pacific all agree. They all provided letters of support for both motions.

The DGN fishery in California has been the target of campaigns such as this one that triggered several negative transfer effects. The NGO saw CTS on the shelves of Henry’s Farmers Market and scheduled a meeting with Henry’s Director of Meat & Seafood to discuss removing it from the shelves because it is not “sustainable.” However, the NGO failed to provide specifics as to why not, so the shark meat remained on the shelves. Six months later the NGO created a petition directed at Henry’s President and CEO and after his inbox filled up, he eventually made the call to remove all shark meat from the product list offered at Henry’s. That year ended up to be Henry’s worst year in seafood sales in the company’s entire history. Also, fishermen were at sea catching CTS during the time of this campaign so when they came to port with the sharks they had caught, seafood buyers could not give fishermen a decent price because their retail clients were starting to reject offers. As a result, most of the shark meat was donated to a local homeless shelter. Nothing against a generous donation, but this was around late November when fishermen could have used that money towards their own families during the holidays. At around $3.50-$5.00 per pound, CTS is an affordable source of protein that is also low in mercury. When you take California caught CTS out of the picture, you open the door to more imported shark meat from countries with less conservation efforts in place and/or other cheap seafood that is less ethically sourced. This is just one example of how a campaign intended to save sharks had negative transfer effects all the way down every link of the market chain and did not save the life of a single shark.

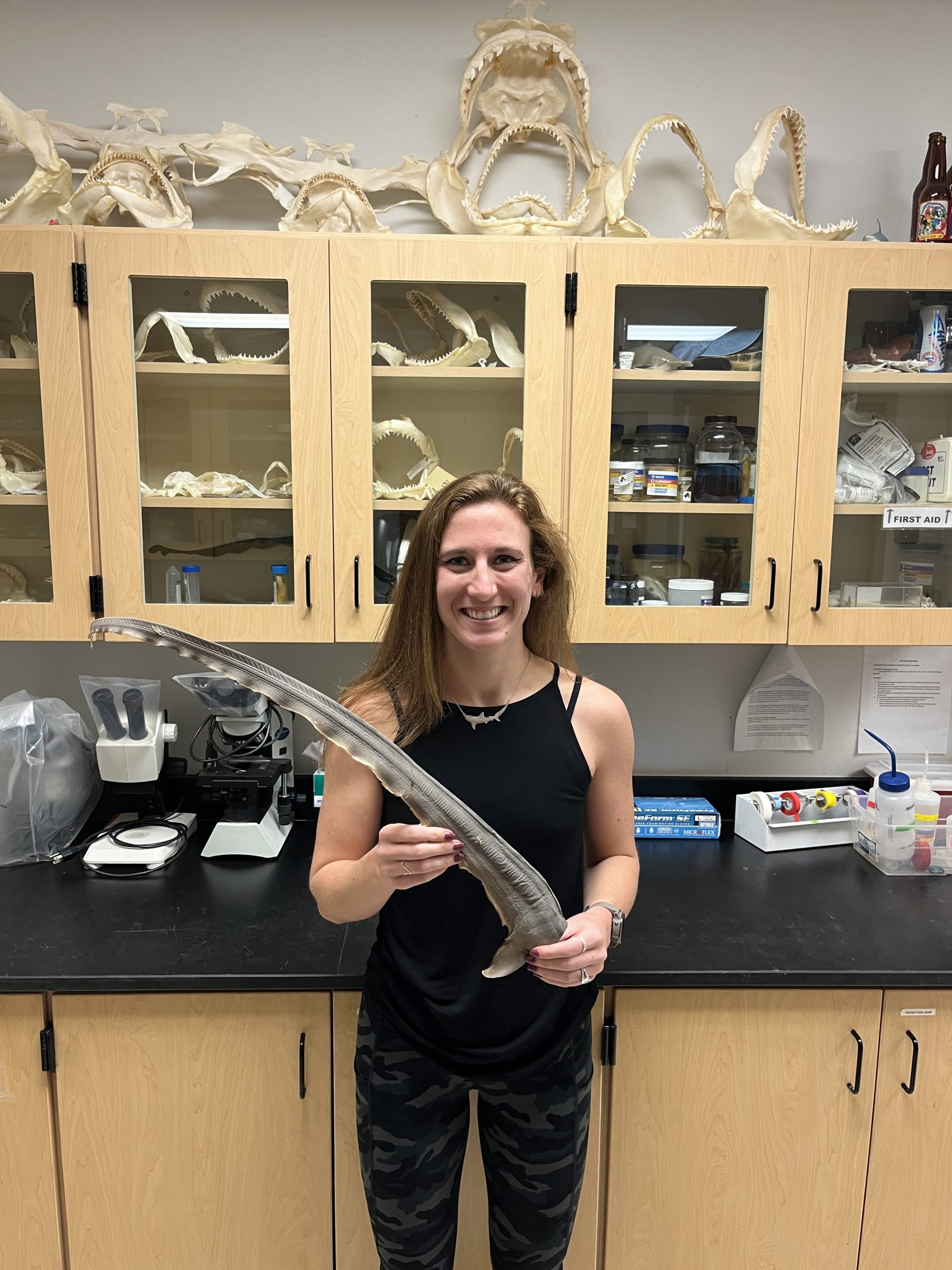

After the collective negative impacts of this campaign and others like it, it was clear that the DGN fishery had an “image problem.” A meeting was initiated by NMFS that included the President of the NGO responsible for the Henry’s petition, DGN fishermen, seafood buyers, Henry’s Director of Meat & Seafood, fisheries biologists, fisheries economists as well as representation from Seafood for the Future and Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch Program. The hope was that everyone involved would leave with a common understanding of the West coast DGN fishery for swordfish and CTS. I had the pleasure of attending this meeting that was held at the Long Beach Aquarium of the Pacific on April 28, 2011. The following statement was agreed on by all parties, “Locally caught common thresher shark comes from a well managed U.S. fishery and is harvested with appropriate methods and safeguards to ensure sustainability.”

Additional workshops were held at the Westin in San Diego on May 10th & 11th, 2011. I ask that you please review the presentations found here, it’s pretty cool stuff. The information from these workshops was instrumental in the Seafood Watch Programs decision to change the rankings of CTS and shortfin mako sharks caught in California and Hawaii from “avoid” to a “good alternative” ranking. The information shared also resulted in Henry’s decision to add California caught CTS and shortfin mako shark back to its list of seafood offered. Consider the negative transfer effects that would occur if we were to have 100% of our swordfish and CTS meat imported from fisheries with less interest in conservation. Or consider how other nations can hopefully use our management efforts here in California as a role model of progressive fisheries management that they can learn from, rather than a fishery that should be “phased out.” I hope you are inspired to learn more about fisheries issues that interest you by investigating both sides of the issue extensively before making up your mind about them and signing some petition that comes around. Our actions have consequences and we owe it to both ourselves and to our oceans to do more homework before jumping to simple conclusions regarding complex issues.

Hello, my name is: Bob.

I am an 8th Grader at Punahou School.

I am taking social studies class.

We are studying local problems, how they are dealt with by the government and how citizens can participate in their government.

The problem I am studying is: “Marine Debris, and how it affects the Hawaiian Islands.”

I am responsible for finding out information about the problem to share with my class.

May I ask you a few questions via this blog?

Is there any other person you can recommend so I can get more information out of?

Do you have any printed information on the problem that you can send me?

If possible, could you please send it by my email given?

Thank you for answering me when you can.

Thanks.

Here are some follow up questions if you wish to further help me:

1. How serious do you believe this problem is in our community. (Hawaiian Islands)

2. How widespread is the problem in the community. (Hawaiian Islands)

3. What might be the cause or causes of the problem?

4. Is there a public policy that deals with the problem?

4b. If there is a public policy that deals with the problem, could you please answer the following questions.

-In what form does it take. (Law, regulation, governmental order, other?)

-Can you please describe the public policy?

-Is the public policy for dealing with the problem inadequate? Could you please briefly explain why?

-If the public policy for dealing with the problem is adequate, is it being poorly implemented or not enforced? Please briefly elaborate on it.

-If no, why do you think there is no policy at this time?

5. Do you think that this is a problem that should be handled by the government? Why?

6. What level and branch of government or governmental agency if any, is responsible for dealing with the problem?

7. What is the government currently doing about the problem?

8. Should the government seek the assistance of civil society and/or the private sphere in dealing with the problem? Why or why not?

9. What disagreements if any, exist in the community about this problem?

10. Who are the major individuals, groups, or organizations taking sides on the problem?

-What is their interest in the problem?

-What positions are they taking?

-What are the advantages and disadvantages of their positions?

-How are they trying to influence our Hawaiian government to adopt their solutions to the problem?

11. If my class, or group develops a policy to deal with this problem, how might we influence the government to adopt our policy. (Statewide)

Thank you for answering my questions.

The transfer effect in the swordfish fishery is a myth being circulated by fishery managers who want to enhance seafood profits, plain and simple. There is no hard data whatsoever that expanding the swordfish fishery here will do anything to change fishing practices elsewhere. The right approach would be to phase out high bycatch fishing gear in the U.S. and require fishing fleets that sell to the U.S. to do the same, as required in U.S. law which is conveniently ignore by National Marine Fisheries Service. Do the right thing and everyone will get on board! Instead of taking the “divide and conquer” approach between fishers and environments. This reminds me of the logging wars in the Northwest where the U.S. government allowed multi-nationals to stripmine the forests while blaming environmentalists for loggers losing their jobs and homes.

Over 22 years ago I was a young lad looking for adventure, so I hired on as a greenhorn on a vessel called the Misty Dawn in St Thomas, USVI. She was a long-liner with a crew of 10.

I was in charge of pretty much every garbage job on the vessel for over a month and I have never worked harder in my entire life.

Our target catch was:

1. Tuna

2. Swordfish

3. Mako

Everything else from pelagic stingrays, deepwater fish, mantas, and other sharks were cut loose. Most were dead. In fact that industry does not have a high survival rate for caught fish.

One our third day of actual operations we were running back up the line and came across a huge, grander, marlin. This beast was over 1000lbs and very dead.

What happened next fundamentally changed my views towards fisheries laws and conservation – forever.

The captain punctured the animals swim bladder retrieved the hook and kicked the carcass overboard. 1000lbs of marketable fish went to the bottom of the Caribbean, just like that.

You can understand my shock and when I queried the captain (he was actually a great guy, I had seen him just hours before jump into shark filled waters to cut loose a hooked manta that was just hanging on), he replied that a recent fisheries law to protect the marlin required all US vessels to cut them loose, even though 90% were already dead and another 5% so messed up they would not survive much longer.

That’s modern day conservation and the complete disconnect between laws and actual animal protections.

I am pretty sure if you search the Internet you will find some conservation org press release congratulating US long line fisheries for, “taking the necessary steps to ensure the survival of the marlin in US and International waters.”

In fact nothing had changed after that law went into effect. Actually something did. The price and demand for swordfish skyrocketed, and the Caribbean population of Hexanchus griseus has enjoyed a 20 year unexpected deepwater buffet, all thanks to fisheries laws designed to save a species.

Next time you see a press release from a conservation org, “congratulating a bold new step” pause for a moment and THINK.

Once a “law of the land” becomes an actual law, the real consequences just begin.

For the untold numbers of dead marlin over the past two decades in the Caribbean, that law did nothing but take thousands of tons of marketable fish and send it to the bottom.

It’s happening right now, today, as I write this, 22 years later.

Hi Bob, thanks for reading! Unfortunately, none of the three authors on this blog work in marine debris, nor are we located in Hawaii, so we’re probably not the best people to ask. Christie Wilcox at Science Sushi (http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/science-sushi/) works in Hawaii and may be able to direct you to a good local marine debris researcher.

Thank you for leading me to an alternative site.

Hello Terri,

Thank you for sharing your opinion even further. I hope you will answer a few questions of mine.

Did you have a chance to review the swordfish presentations that I gave a link to?

If you have, then I’m a bit confused as to why you consider the transfer effects associated with the swordfish fishery to be a myth considering the diversity of the groups involved in the swordfish presentations and the information they shared. If you haven’t seen the presentations yet, I ask that you please do.

Do you have any “hard data” that says that PFMC makes management decisions intended to benefit the seafood industry rather than the resource, or is that a myth that you are circulating? If you believe that, then why do you think the WWF and TNC support the recent motions? Do you suggest they are involved in some profit scheme with NMFS? That may seem like a ridiculous question, but looking at your comment, that’s what I take out of it. Please consider your implications here.

Saying that NFMS is conveniently ignoring laws and suggesting that they have the means to monitor or manage bycatch rates of foreign fleets is a pretty loaded statement. Are you aware of the difference between PFMC and NMFS and what their responsibilities are? They are the National Marine Fisheries Service, not the International Marine Fisheries Service.

Suggesting that I am taking a “divide and conquer” approach between fishers and environmentalists makes me wonder if you know what that term even means.

Your statements make it appear as if you are creating a divide between your organization and other reputable organizations such as WWF. Conflicting information between conservation groups with the same goals is very counterproductive. Making general statements that ignore science kills credibility and discourages cooperation from the very people you should be working with, not against.

The fishermen that I’ve had the pleasure of meeting are some of the most conservation minded and knowledgeable folks that I’ve ever met. Unlike you or I, their livelihoods depend on healthy oceans.

We all want to keep our oceans healthy and we all want fish populations and all other ocean life to thrive. Our oceans benefit when environmental groups, fishermen and fisheries managers (and enforcement, etc.) all come together to work toward common goals.

Another reason that those “marketable” fish are going overboard is because the price for them is a lot lower than the price for other fish. Saw it all the time in California, Alaska, Hawaii. Swordfish $3.50 per pound, Marlin $1 per pound, which goes in the hold an which goes over? (Albacore was only $0.25 per pound, so those weren’t even a question…)

If you are going to only bring back 10,000 lbs of fish, it’s better to bring back the valuable ones. Even when it was the target species, seeing windrows of fish trailing behind a processor because they were not the optimum size for the processing line, or there were too many to process, but they could just take the roe out for caviar and toss the carcass. Profitable, but of questionable sustainablity.

As for the regulations requiring them to be discarded, that happens some, and the goal is that fishers won’t target those species, but when it’s bycatch, it will go overboard. Some fisheries are changing towards a count all or keep all management policy where bycatch is monitored and everything that is caught is counted, whether it’s marketed or not. In those cases, the marketable fish thrown overboard are still considered part of the catch and goes against the overall total allowable catch for the species. Of course, that style of management requires several years of monitoring to enable decent statistics on bycatch rates, discard survivability, etc. That usually involves putting fisheries technicians (observers) on commercial vessels.

Swordfish, bluefin tuna, or shrimp?

I choose chicken every time.

Hopefully U.S. fisheries policy can benefit from 100% observer coverage to create a wave of BLUE JOBs for young marine biologists and then laws will be enforced and followed. The U.S. has the ability to lead the world by using fishing methods less harmful to endangered sea turtles. Let’s do it!

Or, we can complain, weaken rules, and let the ocean creatures who are not able to pop out of the water and attend the PFMC meetings suffer and die for our dinner of swordfish, tuna, or shrimp.

I choose chicken!

🙂

Hello Chris,

How do you suppose NOAA comes up with funding to provide 100% observer coverage of all U.S. fisheries? And even if they could afford to do so, do you really think other nations will follow suit just because we are doing it? Yet another oversimplification, sigh….

Currently, U.S. fisheries are monitored better than any other fisheries that I know of, meanwhile other nations’ destructive practices continue. Evidence suggests that your solution is unrealistic.

Personally I’ve never been a fan of the “don’t eat seafood” argument. Yes, overfishing negatively impacts the environment, but fishing is also a use of the ocean that encourages maintaining a healthy environment. Fishermen and conservationists ultimately both want a healthy ocean, and when working together can hold more environmentally destructive practices such as coastal development and oil drilling in check. By taking a “get everyone off seafood” stance, you’re essentially trying to remove one of the biggest motivators for environmental protection in the ocean.

U.S. fisheries are by no means perfect, but as Jonathan says, we have the best fisheries management in the world right now. Reward that effort by eating seafood caught in the U.S. (a lot of supermarkets actually identify their sources now). If you live in a coastal community, buy as locally as possible. Otherwise the people that you’ll never convince to give up seafood will just be rewarding bad practices committed halfway across the world.

Great points.

If everybody stopped eating seafood, the increase of U.S. agriculture needed to meet consumers protein demands would have it’s own set of negative transfer effects on the environment to say the very least.

Thank you for this very thoughtful explanation of how the fishery is managed.

Thank you, Jennifer for your kind words. I wish more folks were aware of all the great work you all do over at the PFMC.

I’ve heard proposals to give vessels an overall catch limit, and then require them to bring EVERYTHING they catch back to the dock, with the idea that this would eliminate high-grading. (Caveats about enforcement etc.) In return, they can sell it all. That seems likely to be controversial – can you imagine US vessels auctioning off manta rays? – but may be a good strategy to discourage very nonselective gear. It would also reward fisheries that are selective, as Jonathan says DGN are.

Interesting article. The importance and struggle to keep fisheries sustainable is indeed immense. I appreciate your point of view, but I do have some questions and comments.

I think the argument that other countries don’t regulate so we should not either is not a good one. The goal should be to pressure other countries to pass sensible regulations not create an ocean free for all.

You mention that the California Swordfish fishery had a low impact on swordfish populations, but could that not be due to the amount of regulations? If you are proposing reducing regulations certainly that may change the situation and the fishery may have an impact. These things should be modeled and likely have, which is why I would guess NMFS would be managing how they are.

Do you have any data to support the “leaf blower effect”? Are turtle by-catch numbers increasing off shore?

You mentioned that the fishermen were not able to sell their shark meat but were they able to sell the fins? Usually, shark fins are what drive the market for sharks. What percentage of their income comes from fins versus the flesh?

You also mention that the regulations will result in increased imports of shark meat. Is shark meat imported? How much of it is imported? From where? How big an industry is shark meat compared to fins? Are the countries that import sharks really importing mercury laced flesh? Has this been studied or verified or is this propaganda?

I think your argument for less regulation would be strengthened if you could provide more hard data to support your assertions. No, I have not watched the many “presentations” you have linked and perhaps some data are found within. But I would recommend you present the data in your argument.

Cheers.

Australian fisheries are pretty well managed. Just an FYI.

I’ve heard the same Andrew, and that’s great to hear!

Thanks, Andrew!

You bring up many questions and I’ll do my best to answer them.

First, I am not suggesting “that other countries don’t regulate so we should not either” nor am I in favor of “an ocean free for all.”

My words were: “how can we increase landings of swordfish in California without going backwards on management efforts to protect vulnerable and or endangered species?” I am by no means suggesting that I know the answer either. I’m trying to inspire us to consider the question. In my opinion, the motions from the PFMC meeting seem to be a fair and cautious management approach.

The “leaf blower effect” is merely an analogy I used to describe how unilateral conservation regulations on HMS can be ineffective because they travel long distances and are more vulnerable in other oceans then they are here due to lack of bycatch mitigation. International cooperation in bycatch mitigation and management of HMS seems imperative to me if we want to save species. Perhaps the fact that sea turtle populations continue to decline 11 years after the PLCA was enacted is evidence of this.

As of January 1st 2012, CA. fishermen can no longer sell shark fins due to AB 376. Prior to that, shark fins did not drive the market for sharks caught in CA. and I do not know what the fin vs. flesh ratio was. But just to be very clear, CA. fishermen DO NOT fin sharks.

Yes shark meat is imported into the U.S. As far as how much and from where, you can find out here: http://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/st1/trade/cumulative_data/TradeDataDistrict.html

It mostly comes from Mexico and Costa Rica last time I checked. Mercury levels vary from species to species but I know that thresher shark meat is significantly lower in mercury than a lot of other fish out there.

The reason I didn’t include all the information from the swordfish presentations is because I wanted to hopefully inspire folks to want to learn more on their own and make up their own mind, not to mention the fact that this post would have been waaaaay too long….

Here is a query I did using the link on the comment above regarding swordfish imported into California during the month of January 2012:

http://www.st.nmfs.noaa.gov/pls/webpls/trade_dstrct.data_in?qtype=IMP&qmnth=01&qyear=2012&qdistrict=%2C+CA&qproduct=SWORDFISH&qoutput=TABLE

You can see roughly 500,000 lbs. of swordfish was imported into California in just one month this year. Also note the countries it comes from.

Compare that to California swordfish landings during the month of January 2010 found here: http://www.dfg.ca.gov/marine/landings10.asp

You will see that 70,588 lbs. of swordfish was landed in California that month.

Discuss…

Jonathan

You are refreshing.

I was a witness to the donation of the threshar shark in San Diego last year. The total donated topped 6000 pounds. We lost our market and the ability to pay our bills. That has changed this year and we appreciate those that enjoy our product and it’s being available again. Some good came from the crisis. NMFS studied the issue and declared the Threshers are sustainable and low in mecury. We don’t sell the fins. We discard them even though there is some money to be made. CA has a law prohibiting the sale. We fishermen supported the banning of shark finning in the Federal arena also.

The reason I decided to write you is our quest to reduce our bycatch to as close to zero as possible. We use 10Kh accoustic pingers [40 on a net] and this reduced our mammal bycatch by 70%. We have learned other strategies as well. I recently learned one of the “pinger” makers has some new frequencies that are showing good results with some of the mammals we have rare interactions with. There are three categories of interactions.1-2-and 3. Three is the worst and to remain viable a fishery has to be a two. Two years ago our interactions allowed us to make category one! That is amazing with a non selective “wall of death”. It is our hope that with technology we will become a one on a regular basis. Our intial pinger strategies are now being used world wide and without Americans leading the way there won’t be more inprovements.

With a 65% yield on total poundage my boat produced over 50,000 seafood dinners. The state sales tax was close to 75,000 dollars[if you only paid 15.00 for the dinner.

Thank you for a chance to speak out!

Tom

Thanks for commenting, Tom. I was hoping to get a fishermen’s perspective in the comments.

Thank you for mentioning the fact that you guys have been Category 1 before and hope to be on a regular basis in the future. I think that is incredible, great job!

I really like your quote “Our intial pinger strategies are now being used world wide and without Americans leading the way there won’t be more improvements.”

Well said, I couldn’t agree more.

Cheers!

Tough call, Jonathan. I say let them fish. 32 boats, heavy restrictions. If you eliminate the fleet you will never get it back. On the East Coast in the early-90s I worked on a swordfish gillnetter. The fishery was banned two years after I got in it. This was before pingers and drops. Our floats were right on the surface. We could’ve made the fishery cleaner, we didn’t, they shut it down. Maybe for the best. We were dumb and in a fight with the longliners. But the East Coast fishery was very different. The trips were much longer (1-2weeks) and we used longer nets about 1-3 miles of twine. I made great money–paid for my entire college education.

It’s all a compromise. Every fishery decision we make; every decision a manager makes, an environmentalist, a consumer. Some things require us to leave our hearts at the door. I do not want to see American fisheries shut down–what will happen with imported protein? Are we all just going to eat shrimp, tilapia, swai, carp. I don’t know. Maybe.

It’s a shame because the large-mess gillnet is a clean way to harvest fish–but all those horrific photos of dead seals wrapped up like cigar butts in the twine–America feeds on those shots, especially the liberals (of which I am one), and the damn tree-huggers (One of them too).

Let these few boats fish. In all my days on fishing boats–hundreds–I have never seen a dead mola mola, and have seen maybe a few dead leatherbacks–but released many alive.

One day–most fisherman will hate this–we will have “fishing zones” next to Marine Protection Reserves which will be next to wind farms which will be next to LNG terminals which will be next to mussel farms which will be next to sailing and recreational areas which will be next to shipping lanes which will be next to oil.

What a horror show that will be. My liberal heart longs for cleaner more beautiful spaces, of a purity long gone.

It’ll all one day be handed to us by Executive Order from our President. It drives me crazy. All of it. But look how important it all is. Plus all the money it is tired to.

Let these few boats fish for swords and let them market the fish as dayboat caught. Go ahead and put an observer on each boat. Make them only soak their nets for 6 hours. Put vessel tracking systems on board–so we know where they are at every moment, spray paint obscenities on their hulls, make the fisherman feel like shitheads. This happened on Cape Cod, a few codfish gillnetters had their boats spray-painted–it broke my heart seeing it. The boats were only 35 feet long, skiffs really.

I’ve been to other ports throughout Asia. They want the US to shut down their sword and tuna fisheries–fish don’t care about lines on a chart. Better pelagic fishing in US water generally means better fishing outside the “line.”

If I think too hard about this–by day’s end, I’d be bald.

But I make good choices. Or maybe I just make better compromises.

Nice piece Jonathan.

Interesting discussion. One question comes to mind from some of the discussion regarding observer coverage – why should the monitoring costs for this (and other) fisheries be paid for by the federal government, especially in this era of shrinking budgets? The DNG participants profit from (and arguably harm through by-catch) a common pool resource and yet taxpayers pay for the costs of monitoring and enforcement. Would the fishery still be viewed as profitable if all the transaction costs (monitoring, assessment and enforcement) were considered?

Think of the way we fund costs associated with other types of resource extraction – revenues from oil and gas leases, for example. Why are fisheries different? There are some interesting alternative models out there – conservation levies in New Zealand, for example, that fund observer programs, and industry funded programs in Alaska. Maybe it is time to ask the fishery to pay its fair share?

Thank you for commenting, John.

I swear, I learn something every time you write something.

Life is just a buck of choices and it’s getting harder and harder to know if and when we are making the right choice. Instead of going crazy trying to be an expert on it all (which isn’t possible) I’d rather focus on and support folks that are clearly making efforts to do the right thing.

Fortunately our fisheries here in the U.S. seem to be a great example of what I want to support.