Dr. Chris Lowe is a Professor of Marine Biology at California State University Long Beach, and is Director of the CSULB Shark Lab. He has studied California’s great white sharks for more than 10 years, and has written more than 75 peer-reviewed scientific publications. Dr. Lowe also serves on the Board of Directors for the American Elasmobranch Society, the world’s largest professional organization of shark scientists. The following guest post was also submitted as a public comment to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Dr. Chris Lowe is a Professor of Marine Biology at California State University Long Beach, and is Director of the CSULB Shark Lab. He has studied California’s great white sharks for more than 10 years, and has written more than 75 peer-reviewed scientific publications. Dr. Lowe also serves on the Board of Directors for the American Elasmobranch Society, the world’s largest professional organization of shark scientists. The following guest post was also submitted as a public comment to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Comments for consideration on the petition to list white shark as threatened or endangered species:

I am a Professor of Marine Biology and the Director of the CSULB Shark Lab at California State University Long Beach and have been conducting State and Federally permitted white shark research in California since 2002. In addition, as a professional and published shark scientist who has studied a variety of shark species around the world, including white sharks in California, I would like to take this opportunity to express my personal professional opinion in regards to the petition request and the science behind it.

For the most part, I agree with much of the CDFW’s assessment of the population status of white sharks; however, it is my professional opinion, based on the best available scientific data that the petition to list northeast Pacific white sharks as threatened or endangered is not warranted at this time. In fact, I would argue that white sharks represent an excellent example of one of California’s greatest conservation success stories.

Here are my reasons as to why:

1. Previously published population estimates for the northeastern Pacific white sharks are clearly underestimates for many of the reasons pointed out in the CDFW evaluation and there is a growing concern among many shark scientists as to the accuracy of these data. In addition, there is published evidence indicating that the northeastern Pacific white shark population has been growing over the last 10 years based on increased recruitment of young sharks in southern California and Mexico and climbing sea otter mortality due to shark bites. The likely reasons for this population increase can be attributed to:

- -state and federal protection for white sharks significantly reducing juvenile mortality

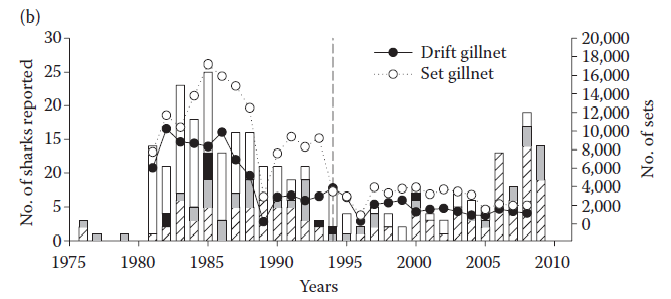

- -significant reductions in gillnet fishing effort since the mid 1990s significantly reducing juvenile mortality

- -recovery of many coastal marine fish species and marine mammals as the result of vastly improved fisheries management (white shark prey base)

- -improved water quality

- -overall public concern for marine resources.

It is important to note that while the arguments posed for listing are precautionary, many or all of the cited risks have already been addressed by State or Federal policies or regulations for over 15 years now (e.g., Federal Clean Water Act, Magnuson-Stevens Act, Highly Migratory Species Management Plan, Marine Mammal Protection Act, CA white shark protection legislation, CA nearshore gillnet ban, etc) and have been documented as reasons for successful recovery of numerous marine habitats and populations.

2. While there is evidence of high contaminant loads found in young white sharks, there is no evidence of any physiological impact or population-level impact. In fact, despite the high levels and known deleterious effects of these same contaminants on marine mammals they have not been shown to have had dramatic effect on pinniped populations, which have been growing at a phenomenal 6% per year over the last 15 years. Since the disposal of these contaminants has been banned for over 40 years now and environmental levels are decreasing, current contaminant loads are likely bearing even a lesser effect on marine populations that those exposed over 20 years ago.

3. While fishery interactions still occur, recent evidence suggests that the post-release survivorship of incidentally caught and released sharks is extremely high (> 95 85.7%) (Lyons et al. in prep). Furthermore, new data indicates that the potential for interaction with gillnets is much less than estimated when we examine the movement patterns of tagged and released sharks in proximity to existing fishing activities. The documented high post-release survivorship of sharks previously caught in gillnets suggests that the impact of gillnet fisheries on white shark survivorship are relatively low and can be further reduced with modifications in fishing practices such as shorter net soak times.

Although concern for adequate protection of apex predators, which naturally have relatively low population sizes is prudent, it is my professional opinion that white sharks should not be considered for listing as threatened or endangered at this time. Time and resources spent evaluating the need for listing of white sharks will reduce critical resources and effort that should be allocated to populations in greater risk. Placing species that truly do not require this level of protection only dilutes the value of this protected status listing. In addition, since I am either collaborating with or knowledgeable of all other ongoing research on white sharks in the Pacific, I can say that there will unlikely be any new findings coming out in the next year that will shed more light on this situation than already currently exists. Finally, it is important to note that the review process itself will also potentially impede our ability to gather new information needed to address data gaps due to increase permitting requirements and research restrictions.

Why do scientists so rarely refer to improvements in research techniques and technology as a possible contributor to increases in population data – or have there not been any improvements over recent years/decades that would impact results? Surely if I have stronger binoculars I will see more birds – but that doesn’t necessarily mean there are more birds…

Improvements in research techniques are unrelated to these observations. Population surveys utilize the same technology year after year on purpose exactly to minimize the opportunity for technology to influence the results. In this case, several unrelated measurements of population status all point to increases since the mid 1990’s.

Chris: Thanks for providing a measured, sensible response to the topic. This will be an “interesting” one to follow with quite a lot at stake.

Cheers, Pete

I quote Chris on just this topic in my new book, ‘The Golden Shore – California’s Love Affair with the Sea’ in my chapter ‘Return of the Beasts.’ I hope he and others will join me for a discussion on the book and raise this issue at the Aquarium of the Pacific in Long Beach on Thur. Feb. 28 7PM

Chris – I totally agree with Peter Nelson. Thanks for providing such clear, concise and accurate information. Hopefully it will be heard by those who make such decisions.

Cheers, Greg

With regards to the NE White Shark population and tracking and research technology. As David has said, the methods to study these sharks have remained pretty much the same up until the last few years. Spot tags, Satelite tags, acoustic tags and old fashioned plate tags that all hopefully accompany pictures of the animals were and are the accepted and widely used methods. It’s only been in the last several years that longer term tags and tagging methods like those used by Dr. Michael Domier have been available. Technology has been a limiting factor as they are basically static, new methods are slow to be adopted due to testing of efficacy and as a result, as David points out here, “Improvements in research techniques are unrelated to these observations.”

As a way to change that and speed things along and speaking for myself. It’s my belief that with the very limited acces to these elusive animals, more needs to be done by those actually on location, to ID and gather as much information of all types on the White Sharks to assist in better data accumulation. This in turn would add more insight on White Shark populations in the NE Pacific Ocean. Whether that be by the research scientists, the eco tour operations such as the one I manage and the fishermen when possible, or all three working together. As for the researchers and tour operators, we are only able to be on location and observing for 3 months out of the year. The tour operators are limited to passive observation only. The access period is due to both permit access and weather windows. While the sharks are active in the NE Pacific / Northern CA. range from late July through January for the most part, we are only able to operate at the Farallones by permit Sept through November.

The researchers in this field all have opinions and research to back them up. It doesn’t all agree all the time if at all. Who is right and who is wrong? For the most part, nobody knows. Definitive anwers on White Sharks are scarce. No one even knows for sure where they breed. It used to be thought they didn’t eat after they left the coast and it’s pinniped rookeries. Even now the head of GFNMS states that adult White Sharks don’t eat fish or squid, just marine mammals. That’s just flat wrong. More data is needed and as quickly as can be gathered by all sources. That’s one of the flaws in this system, not all sources are used. Not all the data is collated. I’ve been working to try and be allowed by the GFNMS to gather more info but am being told yearly that the operation is not qualified to gather basic data. To me this is seems an unfortunate waste of badly needed sea time as well as a waste of opportunity for citizen science and public stewardship. People want to help and be involved. I know I do. But since I can’t be involved the way I want, I’ll sit and watch the debate and machinations from the sidelines. It’s going to be interesting to watch the developements of the various research camps here in California. In the past, this big pond has proven to be a very small place so I expect there will be a few sparks. Hopefully some good answers will float up to the surface before too long.

Greg Barron

Incredible Adventures

I don’t do a lot of work focused on sharks, and have nowhere near the scientific knowledge of white sharks as Dr. Lowe. It is encouraging to hear that there is some evidence that white shark populations may be increasing in some areas. Still, it seems to me that there are several issues here worth considering from other angles. For example, incidences of shark bycatch associated with gill nets would be expected to decline if there were fewer sharks left to be caught in nets. Climbing sea otter mortality due to shark bites could partly be a result of declines of other shark prey species. It is unquestionably a good thing that successful conservation efforts have prevented many toxic materials from being dumped into the ocean, but it’s a stretch to assume that this does not continue to impact marine life. That sharks can often survive being caught in gillnets is great; presumably an ESA listing would help add weight to efforts to mandate measures like reductions in soak times that would increase their chances even more. And even if it is true that a population is growing, this needs to be considered relative to other factors, such as the historical population size, growth rates, genetic diversity, etc.

As for the argument that we should only list the most endangered species to avoid taking attention away from others which more urgently need conservation, that isn’t the way ESA is supposed to work. If species meet the criteria, they should be listed. It would be better to ensure that relevant agencies have adequate resources to meet their requirements under the law than to effectively water down the law before it is implemented.

As to Dr. Lowe’s final point, that the ESA review process might impede research efforts, this concern comes up occasionally from scientists but rarely ends up happening. More to the point, it is much easier to study a thriving population than one that is depleted – or extinct.

John Hocevar

Greenpeace

Thanks for your thoughtful comment, John!

“As for the argument that we should only list the most endangered species to avoid taking attention away from others which more urgently need conservation, that isn’t the way ESA is supposed to work. If species meet the criteria, they should be listed.”

Certainly, but it seems to be the way that ESA does work. Responding to a petition takes a lot of resources, and particularly in today’s budget-cutting climate, resources are scarce. I’d love to see every species deserving of ESA attention receive it, but in the meantime, realpolitick suggests that we should prioritize.

As someone who did their PhD mostly on pollutants in marine mammals, I have big, big issues with this comment in the article: “In fact, despite the high levels and known deleterious effects of these same contaminants on marine mammals they have not been shown to have had dramatic effect on pinniped populations, which have been growing at a phenomenal 6% per year over the last 15 years.” You have to put this into context – what was the size of the original population. Is it rebounding back from depleted levels? Pinnipeds are protected under the marine mammal protection act,so other forms of mortality are reduced. If so 6% may be on the low end. What about first pup mortality in pinnipeds. Pinnpeds can dump much of their organic contaminant burden on their first offspring via placental transfer and lactation – not such an option in sharks. Later pups in an aging population my not face so many pollutant-related problems. You are basically comparing apples with oranges. Plus there have been pollution-related reductions in reproductive rates reported in pinnpeds in various parts of the world, as well as pollution linked disease outbreaks. Also the comment about the length of time since certain contaminant production was banned – makes a difference for DDT which gets broken down to the less toxic, but still biomagnifying/accumulating and capable of health impacts DDE. Not so much with mercury and other contaminants.

From a political stand point – it takes a long time to get a species listed on the ESA and an even longer time to get conservation actions in place, and sometimes longer for any effect to be seen. If the listing is shot down now, it could be a decade or more before a second chance, and possibly longer for benefits to be seen.

I think it’s easy to forget when dealing with high-profile threatened species that the situation is not always “must protect”. If the supporting science is well thought out, peer-reviewed, and (most importantly) objective, then a decision to not list a species must be considered as valid as a decision to list. This isn’t always an easy pill to swallow for anyone involved in conservation activities, but ignoring good science because it doesn’t agree with an agenda undermines the entire process.

That being said, rejecting white sharks completely from ESA protection based solely on better protection for juvenile sharks may not be the best idea. The research above doesn’t indicate if population recruitment is any higher than in previous decades, or if adult mortality has been affected.

I agree that while the factors listed are all positive signs that action has been taken, and the population is showing signs of recovery, I still believe that the white shark is deserving of federal protection. Sharks found in U.S. waters at a certain time of year will not always remain there, and can move into other territorial waters where strict conservation efforts may be lacking. For the species to be truly protected, its entire range must be considered, and a U.S. lisitng would go a long way to help the global population.

As much as debate can be found in the pollution / pinniped statements that are reasonable from both of you, and the undisputable statement that polutants are bad in general and affect the entire ecosystem, the undeniable fact that remains is that the pinniped populations on the California coast have been making large gains yearly and are apparently rebounding. 5 species of growing pinniped populations are found locally to the SF Bay and further to Monterey and beyond. Fur Seals are now found yearly at SE Farallon where before they had been eradicated from the islands and coast as far north as Oregon/Washington. As to whether populations of White Sharks are growing or not, several times I’ve heard Sal Jorgensen present TOPP data that shows an increase of White Sharks that seems to be following the increase of pinniped populations. Of course, that’s countered by what TOPP has been saying about the actual population now. So, the question that remains is this and Chris came out and said it. Is the White Shark in need of being accorded the new protections? If the population is growing due to the conditions now and recently implemented policy, then as he says, maybe they don’t need to be listed. If the population is as very low as TOPP says and only just beginning to recover then perhaps the additional help is warranted to get the population increased. Here’s the rub as I see it. What if the population has been static? What if this is a normal population concentration for the animals. Nobody really knows what the population of the White Shark has been or is supposed to be. Nobody knows because there hasn’t been enough study on the White Shark or enough people studying it.

Some sharks are also able to offload contaminants to their pups (although I dont know about white sharks). Also, white sharks are awarded protection in California. It is still illegal to land one.

I see your point about ESP listing…it does take a long time to list a species. That being said that should not be a reason for listing a species that does not need it. ESP is not a pre-emptive strike but reserved for the species that desperately need it.

I do need to clarify one of the statistics I mentioned in my public comments submitted on Feb. 5th… New analysis of the data indicate that post-release survivorship of sharks caught in gillnets is actually 85.7% (Lyons et al. Unpubl data).

Greg: I think you make an important point regarding the potential contribution that folks other than academic or management scientists can make here. One significant difficulty, as you may well know, is that turning your observations into defensible data (for example, that could be used in determining whether a species qualified for protection under the ESA) is a real challenge. No doubt, it can be done, but it’d require designing a protocol with the cooperation of scientists, managers and enthusiasts together. Citizen science has been used with excellent effect, and I’d be interested in talking to you more about this possibility. My work these days is primarily with fishermen, but I’m intrigued. Please, get in touch! Cheers, Pete

Hi Pete,

Now that is exactly what I’ve been saying for the last 8 years of doing the White Shark work. That being said, regular citizens can collect basic data very easily and defensible data is actually very easy to collect particularly if given some direction by researchers or someone with a plan. For instance, these are things I’ve been collecting the last 8 years or so of diving with White Sharks; Sighting data, numbers of animals, numbers of sightings, when, where, how long, weather conditions, temps, images when available, predations, lack of predations, decoy attraction, decoy interaction, decoy efficacy, other animal sightings including pinnipeds or their lack, size estimates of sharks when seen, sex if possible, day or night sightings, feeding, interaction with vessels, no interaction with vessels and the list goes on. We don’t need to tag but if we could get the animals to actually get close enough to see we could do a visual image ID collection. That is something that can be discussed and is but my point is that this is all data point collection and is valuable. You don’t need a PHD to do this work as long as it’s supervised and structured. What’s more, the people that travel to see these animals really really want to assist in the process. It gives them a feeling of stewardship and the ability to say they were part of the discovery process. You would be amazed at how much people really want to be included in things they feel are important. It’s how I got started for one thing. Citizen science has been used to good effect for centuries. It’s time that we look to our history for confirmation. I make the same offer to every academic I come in contact with every year. So far no takers which seems a waste of resource and potential. I will make room on the boat for anyone doing continuous work with the sharks as long as it’s something the people on the boat can help with or be a participant in and as long as I’m running the trips. Lot’s of simple stuff that falls in to that category. Send me an email and we can talk more should you want. Same goes to you David but you’ve heard that from me before, something about being 2500 miles away and not in this particular area of study.

gbarron@hiwheel.com

Greg Barron

Incredible Adventures