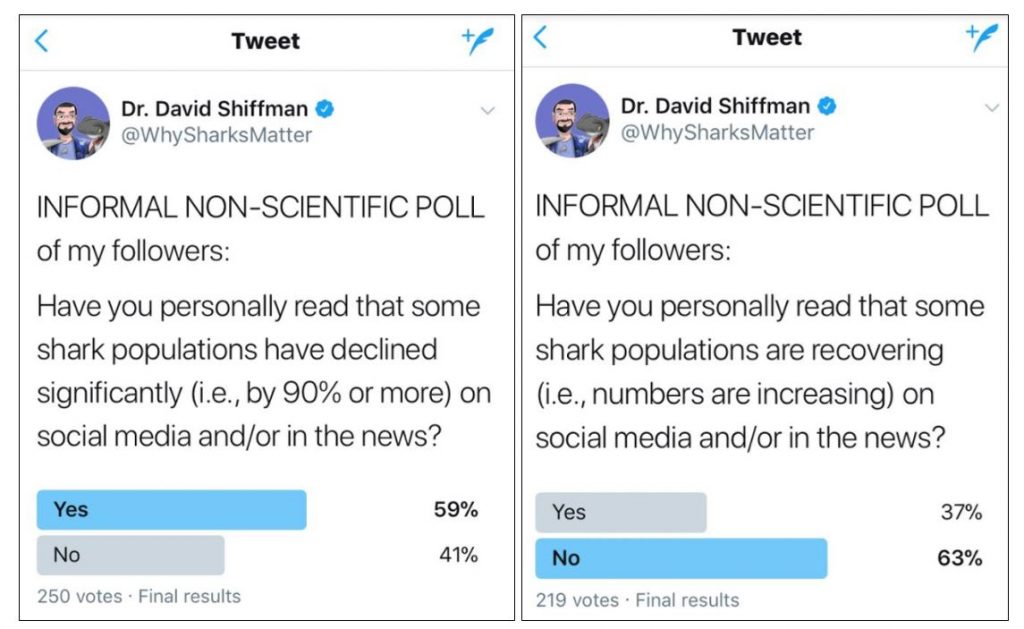

Did you know that some shark populations have declined due to overfishing? Did you know that some once-declined shark populations have recovered? If you’re like my twitter followers, it’s likely that you’ve heard the bad news, but have not heard the good news.

Why does this matter?

It’s important to share bad news so that people know there’s a problem, and that we need to act to solve that problem. However, it’s also important to share good news so that people know that a problem is solvable! This idea was behind the birth of the #OceanOptimism online outreach campaign.

Dr. Nancy Knowlton, the Sant Chair of Marine Science at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, has been a leader in the #OceanOptimism campaign since the beginning. She had this to say about this powerful movement in conservation communications:

“It was launched in 2014 with the idea of highlighting stories about things that were working in marine conservation. More broadly, it captures the idea that in a media world where “if it bleeds it leads,” the examples of good news for the ocean get drowned out and ignored. This doesn’t mean there is no reason to be concerned, deeply concerned in fact, about the threats the ocean faces and the damage that has already occurred. But to ignore the successes that have been achieved is counterproductive!

“First, we have so much to learn about why these successes have occurred, so that they can be scaled up and/or replicated. Second, unrelenting doom and gloom without the solutions leads to apathy not action. Social scientists have actually known this for ages and I see this regularly. For example, quite a few students have told me that they almost left the field of conservation because their courses were so depressing (and I don’t meet the students that did leave). We need those people working to make thing better! Finally, every conservation success has a powerful story with the classic “hero’s journey” structure. Stories are by far the most effective way to convey information to the public!” – Dr. Nancy Knowlton

#OceanOptimism and Shark Population Increases

A 2013 analysis of sharks in global media coverage, which I am following up on as part of my PostDoc research, noted a striking disparity in media coverage of shark conservation topics. They found that 17% percent of media articles about sharks mentioned topics related to shark population declines, but only 4% mentioned any kind of successful conservation interventions. Similarly, a quick search of the AltMetrics found that the most-covered papers on shark population declines get much, much more coverage than the most-covered papers on shark population recoveries. My own analysis is ongoing, so stay tuned, but a preliminary look at the data seems to confirm these trends.

“But what if there isn’t any media coverage of shark population increases because shark populations are declining everywhere?” you might ask. “What if no one hears the good news because there really isn’t any good news?” Fortunately for sharks, this is not the case! There have indeed been several cases of shark population increases, in several species for several reasons!

Great white sharks off New England

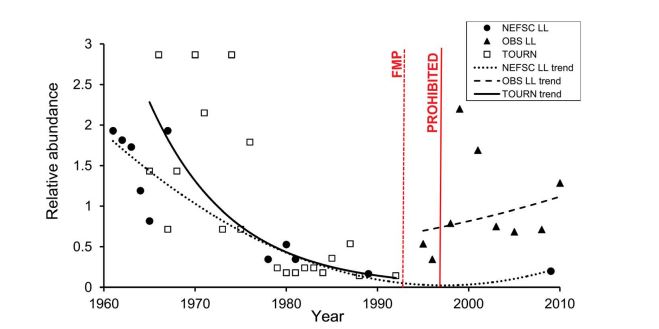

Great white sharks are one of the most iconic shark species, made (in)famous by Jaws and decades of Shark Week shows. Partly because of their fame (and not because they’re the most threatened shark species) they were some of the first shark species to benefit from conservation protections around the world. A 2014 analysis by Curtis and friends found that these protections have helped to recover great white populations!

“We estimated that the white shark population had declined ~60-70% during the 1970s-80s. However, after fisheries management regulations were put in place prohibiting their retention in the 1990s, we saw an increasing trend in relative abundance indicating that as of 2009 (the terminal year of our analysis) the population was back to ~30% below its historic levels. So, they’re not yet fully recovered, but apparently moving in the right direction!”

“The increases we observed came after the implementation of fisheries management regulations protecting the species. It appears that these regulations had their intended effect of reducing fishing mortality, and allowing the population to recover. Increasing regulations and broad reductions in fishing effort in a number of other fisheries that catch white sharks as bycatch (e.g., trawl, gillnet, and longline fisheries) also likely contributed to the apparent increases. In any case, the simplest explanation is that fishing mortality was reduced to a level that has allowed the stock to rebuild. This is a good for the recovery of an important marine predator population, which is in turn a positive sign for the health of its marine ecosystem. It also showed us that relatively simple fisheries management measures (i.e., ‘If you accidentally catch this species, toss it back.’) can rebuild a population, even if the species is very slow-growing, long-lived, and has naturally low population numbers.”

“For a long time, all we’ve heard is bad news when it comes to shark populations. But lots of people (scientists, governments, NGOs, etc.) have now been working for decades to protect sharks through various mechanisms. Where tangible progress has been made in legally conserving shark populations (e.g., U.S., Australia, New Zealand, etc.), we are finally starting to see positive outcomes, as one would hope.” – Dr. Tobey Curtis.

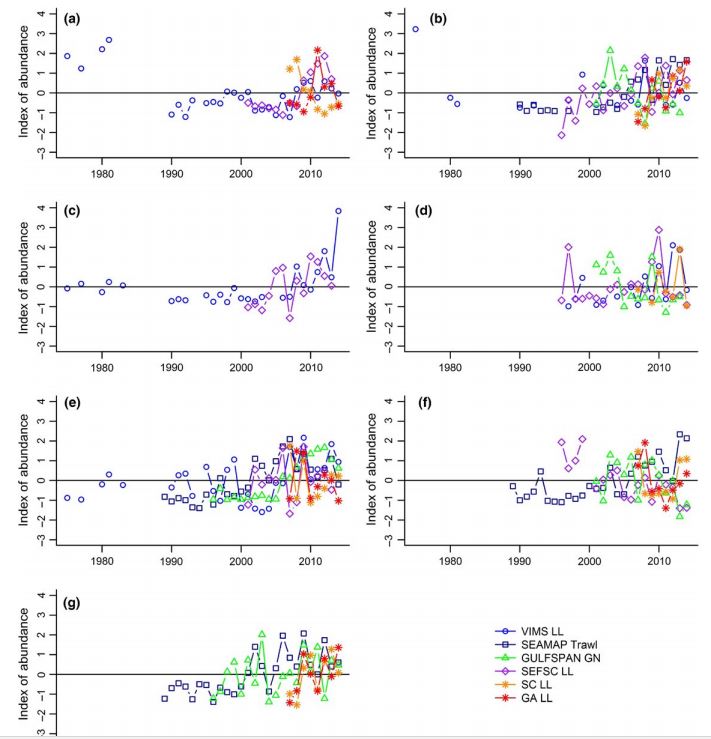

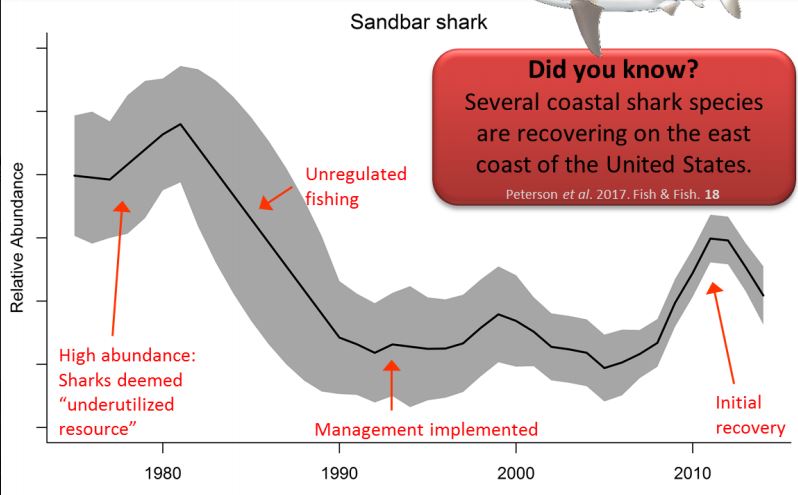

Not all shark species have the fame of great whites, including my beloved sandbar shark—though anyone who has been to an aquarium has likely seen a sandbar shark, few people have heard of them. Despite more limited public attention, many of these species face fishing pressure and conservation threats. That’s why I was so excited by a 2017 paper by Peterson and friends! Virginia Institute of Marine Science Ph.D. student Cassidy Peterson and her team found that populations of several lesser-known shark species are increasing!

“Populations are increasing because of changes in management measures over the past 2.5 decades. The results from the large coastal species (sandbar, blacktip, tiger, spinner) were remarkably consistent. They very clearly depict high abundance in the 1970s, declines through the 1980s into the early 1990s, followed by a species-specific period of depressed abundance (reflective of the different life history of each species), and rebounding increases into the 2010s. This exactly tracks the history of exploitation and management within this fishery. Unregulated fishing quickly led to population declines of these slow-growing shark populations.” ”

The first shark fishery management plan was enacted in 1993, effectively leveling off depletions. Blacktip sharks, which reach sexual maturity at 6-7 years on average, started to increase in the mid- to late-1990s. Contrarily, female sandbar sharks don’t mature until an average of 14 years, and correspondingly, they did not start to show signs of recovery until the late 2000s. Overall, all large coastal shark species are showing increases in abundances into present times. All small coastal shark stocks are showing generally stable or increasing trends in relative abundance to present time with one exception. Blacknose sharks in the Gulf of Mexico showed decreasing abundance from the mid-1990s onward. Blacknose sharks are susceptible to bycatch within the shrimp trawl fishery, potentially providing a mechanism governing their declining abundances in the Gulf.”

“The feeling regarding shark population dynamics, especially to the public, has been so “doom and gloom” for the past two decades. Given the population collapses experienced by several pelagic and coastal shark species in the 1980s and 1990s, this negative mindset is hardly surprising. Despite progress in management, outreach, and increases in shark population sizes, this disparaging attitude has seemingly not changed. I am hopeful that emphasizing the initial recovery of some coastal shark populations will help to alleviate this inherent negative attitude regarding shark population status. At least within the United States, we can start to shift away from the “doom and gloom” era regarding shark abundance.”- Cassidy Peterson

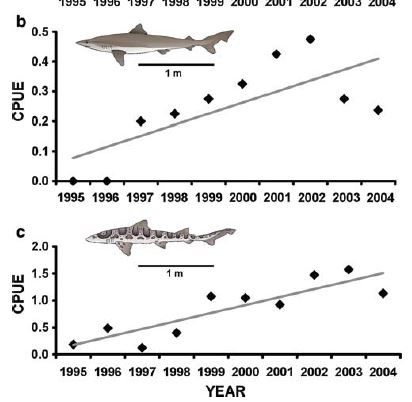

Leopard and Soupfin sharks off Southern California

A paper by Daniel Pondella and Larry Allen found that two shark species have been increasing in population since the 1994 ban on gill nets within the Southern California bight. This fishing gear caught lots of soupfin and leopard sharks as bycatch, and since it has been removed, these sharks’ populations have been recovering despite ongoing fisheries for them.

Here’s what Larry, a Professor of Biology at CSU Northridge, had to say:

“We were doing gillnet surveys throughout the SoCal bight, so we encountered lots of bycatch species from the gillnet fishery. We started the year after the California coastal gillnet ban, in 1995. We were surprised to find juvenile soupfin sharks, and they were growing up! Then leopard sharks! We noticed that not only the white seabass populations were increasing, but also those sharks! We’re pretty sure it’s because those species were no longer being caught as bycatch in gillnets in nearshore waters. We decided to put that out to the world, because it was some good news for a change. As everyone was predicting the end of the world we found a success story!

We tried to publish in Science, Nature, and PNAS (where high-profile papers on shark declines have been published,) and they wouldn’t accept it! A reviewer just didn’t believe the data!

It’s not all dire news. You can do things that work, things that help, things that are more along the lines of classical fisheries management tools! If you protect them, they will return! Here we have a success story, and we need to publicize it!” -Dr. Larry Allen

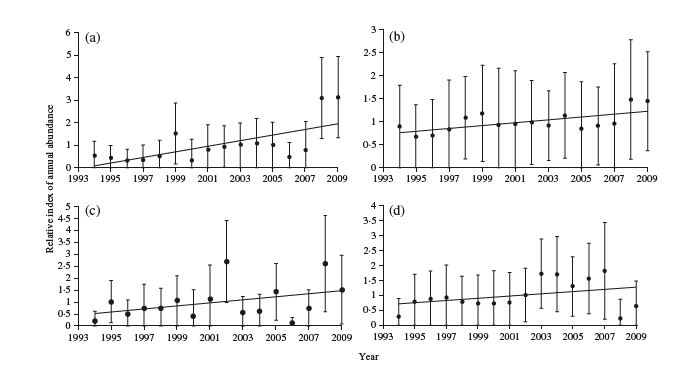

4 shark species off the Eastern Seaboard

A 2012 study by Dr. John Carlson and friends found recoveries in 4 shark populations. Since the US instituted a fisheries management plan in 1993, populations of spinner sharks increased by 14%, populations of bull sharks increased by 12%, populations of lemon sharks increased by 6%, and populations of tiger sharks increased by 3%.

Here’s what Dr. John Carlson, a NOAA Fisheries Research Biologist, had to say:

“Likely due to several prominent publications, the abundance of large coastal sharks in the northwest Atlantic Ocean is generally regarded to have significantly declined. While large coastal shark populations did decline during the 1970s and 1980s, the decline is not as dramatic as described in some of these publications and many of these populations have at least started to recover. Because there has been interest in increasing conservation measures for species that are not harvested significantly in commercial fisheries, to better understand the status of these species I determined abundance trends for spinner, bull, lemon and tiger shark using data from the US commercial shark fishery. While the status of shark populations should not be based exclusively on abundance trend information, but ultimately on stock assessment models, results suggest these species are increasing in abundance about the time commercial and recreational measures had been implemented. This provides evidence that these measure are working for many species and populations will likely continue to increase into the future.” -Dr. John Carlson.

What do these recoveries have in common?

Here I’ve highlighted four stories of shark population recoveries. They include large and small sharks, highly migratory species and homebodies, those targeted by commercial fisheries and those caught as bycatch. These stories do have two things in common, however.

1. All these examples happened in US waters. There are two explanations for this. One is research effort: quite simply, more people are studying sharks (and tracking their populations) in the US than anywhere else, and more population tracking means more data on population trends. Likely more importantly, however, is that the US has some of the best managed shark fisheries on Earth . When shark fisheries are well-managed, populations can recover. When they’re poorly managed, populations decline.

2. None of these examples required a total ban on shark fishing to achieve population recoveries. In 3 of these examples, the primary factor attributed to the recovery of shark populations is NOAA’s Fisheries Management Plan, not a total ban on shark fishing. The other banned a particularly destructive gear type of fishing gear in some places, but not all fishing. These fisheries management tools helped targeted species as well as bycatch species to recover, and it did so while allowing for sustainable exploitation of sharks, providing protein to the global marketplace while employing fishermen. Bans aren’t the only answer, and traditional fisheries management can work.

“It’s personally frustrating to still see so many people, including knowledgeable and respected scientists, resistant to the idea that shark populations can be rebuilt and managed sustainably. There’s a lot of good reason for concern looking at the state of numerous shark populations around the world. But it has now been clearly demonstrated that where there is a will to implement and enforce measures that sufficiently reduce fishing mortality rates, just like other fish species, sharks have the capacity to recover. It’s not simple, it can take a long time, and there are no silver bullets, but it is possible. Collectively, we should be learning from these demonstrated successes!” – Dr. Tobey Curtis

Share the good news!

In cases where shark populations are increasing, we need to share the good news! It’s important to avoid burnout or the “boy who cried wolf” effect, and it’s important to highlight solutions that work so they can be copied elsewhere. There’s no question that many shark populations are in trouble, but there’s also no question that we’ve found effective ways to rebuild shark populations. While we can’t forget that many species of sharks are in trouble, we can and should celebrate successes as we work to implement them elsewhere. Shark population increases show that shark conservation works, and if that isn’t grounds for #OceanOptimism , what is?

If you appreciate my shark research and conservation outreach, please consider supporting me on Patreon! Any amount is appreciated, and supporters get exclusive rewards!

Author’s note: I have seen some shark conservation news shared using #OceanOptimism, but it is almost always “we banned fishing for this species,” or “this species got listed under CITES,” or something like that. While newly enacted conservation measures are important news, I think it’s reasonable to argue that celebrating new regulations is not the same thing as celebrating the actual documented success of past efforts.