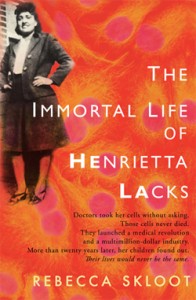

I could write a hundred different kinds of reviews for Rebecca Skloot’s new book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks and they would all be nothing but favorable. The book has three take-home points: informed consent, privacy issues, and race/class relations. One of the biggest things to note about the book, however, is the personal story of the author included in the book – the challenges included in doing ethnographic research. Yet it’s precisely this perspective that makes the book so spectacular, finally bringing Henrietta’s family the recognition they deserve. Recognition that remains the only thing they’ve ever asked for in return for their family’s donation and subsequent sacrifices.

The issue of informed consent is central to the story. Henrietta, the woman behind the first cell sample that revolutionized biomedical research, never agreed to have her cells used in research, later to become immortal. Her family never received any benefits or recognition for her donation. It’s not that she would have said no, or even requested any compensation. She didn’t have the chance. Furthermore, as a result of not even knowing her cells had been kept for research, her family had absolutely no way to prepare for the consequences of exploding HeLa research in the coming years.

Skloot made certain to not only recognize Henrietta in the story of HeLa but the entire family, from those who lost a mother in the process to those who simply had no trust in doctors as a result of their family history. The new ethical issues that have resulted from six decades of tissue culture and genetic research continued to haunt the family directly as a result of the persistance of HeLa. We can now identify all sorts of personal information from a single sample of cells, from identity to genetic disease load. At first, this manifested itself as doctors knocking on the door of the family asking for blood samples. Now, it looms as a threat of denied health insurance and private information made public just by virtue of the fact that the family shares genes with the famous Henrietta. These advances raise the question of whether the donor should be allowed to give their cells with strings attached in order to protect their identity. Considering that cells are still routinely kept from medical procedures, including baby deliveries, there’s a wealth of private information that lies in limbo.

Finally, there is the continuing role of race in medical care and research. Skloot situates Henrietta’s story well amongst the long list of ethical violations against black communities. From the history of John Hopkins as a research facility dedicated to the black and poor communities in Baltimore to the torturous conditions of the Negro sanitarium Henrietta’s daughter lived out her final days, the Lacks family’s history is routinely scarred by race relations. Though race issues may have tamed over the ensuing decades, the poor are still susceptible to a different standard of care. The issue of informed consent comes in here again – the poor also tend not to have the same level of education, often not high enough to understand basic cellular biology critical in making an educated decision about a consent form. So often the form is just shoved under some stressed family member’s nose filled with jargon and legal terminology, so the definition of ‘informed’ is still a hazy one. One that’s going to take more than time to fix. The contribution of a few doctors in the HeLa story to spending time with the Lacks family and truly explaining the history, the medicine, and the science behind HeLa was critical to making peace with the family. Rebecca Skloot played a large role in this peace through her relationship with the family.

Although the book is couched as a nonfiction scientific and historic work, the story is really one told through an ethnographic approach. The book was 15 years in the making, and as told by Skloot in the book, largely spent on the front porches of the Lacks family in Clover gaining their trust. Letting the family understand her position, her goals, her personal history and always waiting for them to make the first move in the developing relationship was critical to the rich detail that made the book so thrilling. Writing from the first person and including direct quotes from her conversations also pays homage not only to social science methods and philosophy that the researcher is never separate from the researched community, but adds a connection between the various storyline that makes the book read like a novel. She was able to make the reader empathize with the family by giving enough detail to understand their frustration with the scientific institution, even as a scientist myself. It also makes apparent just how small the world is, to realize how many completely different groups of people were involved the story of one woman’s cells.

Overall, the book was a fantastic, informative, and enthralling read. I couldn’t put it down. In addition, it gave me a lot to think about and I look forward to many sparked discussions in medical ethics. Not to mention the Lacks’ finally got the recognition they’ve tried to get for decades.

~Bluegrass Blue Crab

ps. There’s lots already written about the book even though it’s already been out for a few days. Here’s a shoutout to some well-written reviews:

Dr. Isis’ My Mother’s Hairbrush and the Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks

Amy, I really like how you approached this review and added another perspective to this much-discussed work. Until I read your review, I hadn’t appreciated how Skloot’s work with the family could be considered an ethnographic approach.

Well done. Hope to get out and see y’all soon.