David Ebert has been researching sharks and their relatives (the rays, skates, and ghost sharks) around the world for more than three decades focusing his research on the biology, ecology and systematics of this enigmatic fish group. His current research efforts are focused on finding, documenting, and bring awareness to the world’s “lost sharks”. If you would like to learn more please see our crowd funding project “Looking for Lost Sharks: An Exploration of Discovery through the Western Indian Ocean” and consider making a donation. The more we raise, the more sharks we can name and the more schools we will be able to reach.

David Ebert has been researching sharks and their relatives (the rays, skates, and ghost sharks) around the world for more than three decades focusing his research on the biology, ecology and systematics of this enigmatic fish group. His current research efforts are focused on finding, documenting, and bring awareness to the world’s “lost sharks”. If you would like to learn more please see our crowd funding project “Looking for Lost Sharks: An Exploration of Discovery through the Western Indian Ocean” and consider making a donation. The more we raise, the more sharks we can name and the more schools we will be able to reach.

Jaws, the mere mention of the movie conjures up images of a large triangular fin cutting through the water, beneath it a large fearsome-looking toothy shark swimming with a sense of authority, a purpose. One of the movie’s trailers at the time hyped the fact that this was a mindless eating machine!

I recall seeing the movie Jaws in the theater for the first time during my high school days in the summer of 1975. It was the first big summer blockbuster film, it was something new to audiences, and certainly new to me. Prior to the film’s release people generally did not anticipate such great summertime entertainment from movies like Jaws and subsequently Star Wars (released in 1977). These were fun movies to see with your friends and spend an afternoon or evening afterwards talking about certain scenes or dialog from the movie, “You’re gonna need a bigger boat”; remember this was back in the pre-iPhone, Facebook, Twitter, social media era when kids actually spent time together talking with each other, without the aid of electronic devices and no texting!

The movie as an ancillary and an unintended consequence brought a lot of attention to sharks, both good and not so good. Shark attacks that were of minimal media attention became big news stories, catching big sharks became a sport and shark diving became popular; all of this after the movie’s release. A few high profile shark attacks, one in particular in Monterey that made international news, only further fueled the public’s fascination and fear of sharks. Just going into the water suddenly became an adventure, with the prospects (however unlikely) that one may see a shark. It certainly put the public’s awareness of sharks in their conscience.

Ironically, the actual story in the book Jaws was quite different from the movie. It has been widely commented on that Peter Benchley, who later became a champion of shark conservation, would not have written the book if he had known the negative consequences it had on sharks. In his defense though, and having grown up during this time, I doubt anyone could have foreseen prior to the movie’s release just what impact it would have on society.

The negative consequences of sharks being overfished, culled from popular beaches or fished for sport have been well documented. It is hard to find an article, any article, that does not state and restate that sharks are overfished and populations declining globally.

However, less reported on is the positive aspects that the movie brought about for sharks. Yes, I said positive aspects!

Prior to the movie’s release, sharks were still caught in target and non-target fisheries, but these activities were mostly occurring in the dark, with little to no attention being paid. The majority of shark research was essentially focused on the rare phenomenon of shark attacks, and was mostly funded by the Office of Naval Research. The research mainly focused on developing shark repellants to be used by survivors of sea disasters. This resulted from World War II when horrific stories spread of downed pilots and sailors who were lost at sea and attacked by sharks. The most famous of which was the USS Indianapolis, the story of which was incorporate into a now famous scene from the movie. A little known, and forgotten fact, is that Leonard Compagno’s 1984 “Sharks of the World” volumes produced by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) was funded by the Office of Naval Research as part of this program; Leonard by the way was my major advisor on my Ph.D. committee.

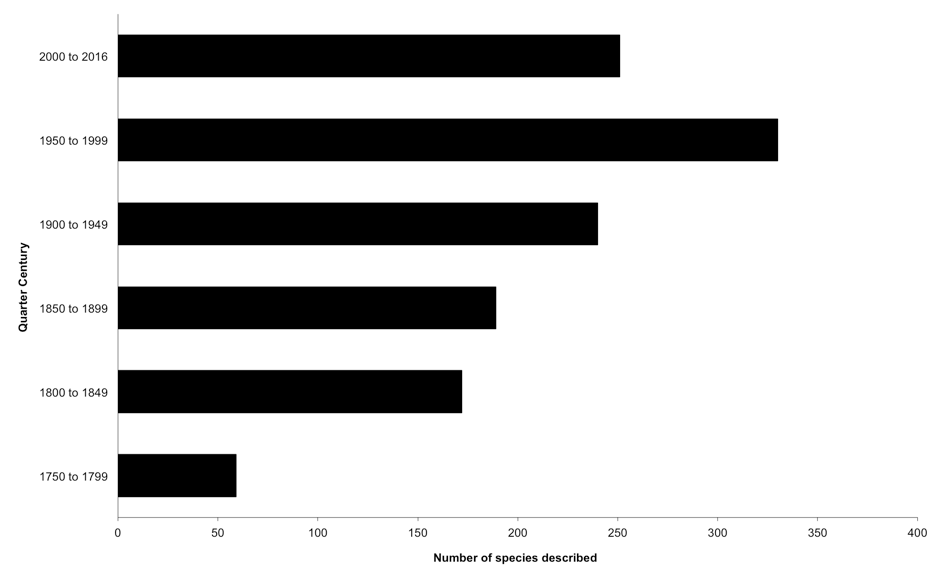

The other area of shark research prior to the mid-1970s was almost exclusively taxonomic based, and with few exceptions done mostly as side projects to more important bony fish systematics. Except for a few dedicated scientists, who mainly studied their taxonomy, virtually nothing was known about their life histories. Most books at the time listed the number of known species at about 250 to 300. Shark life histories and ecology for the most part was virtually unstudied. Stewart Springer, well known for his research on sharks, both on their taxonomy and life history, wrote one of the first extensive papers on the life history and ecology of the sandbar shark in 1960. At the time, it was one of the few and perhaps best known papers on the life history of these fascinating creatures.

All that changed however after the release of Jaws. Yes, sharks came into people’s conscience, but something else happen that has received less attention. The public’s fascination with sharks after Jaws came out lead to many new research opportunities that did not focus on shark attacks. People were actually curious to know more about the fish behind the myth.

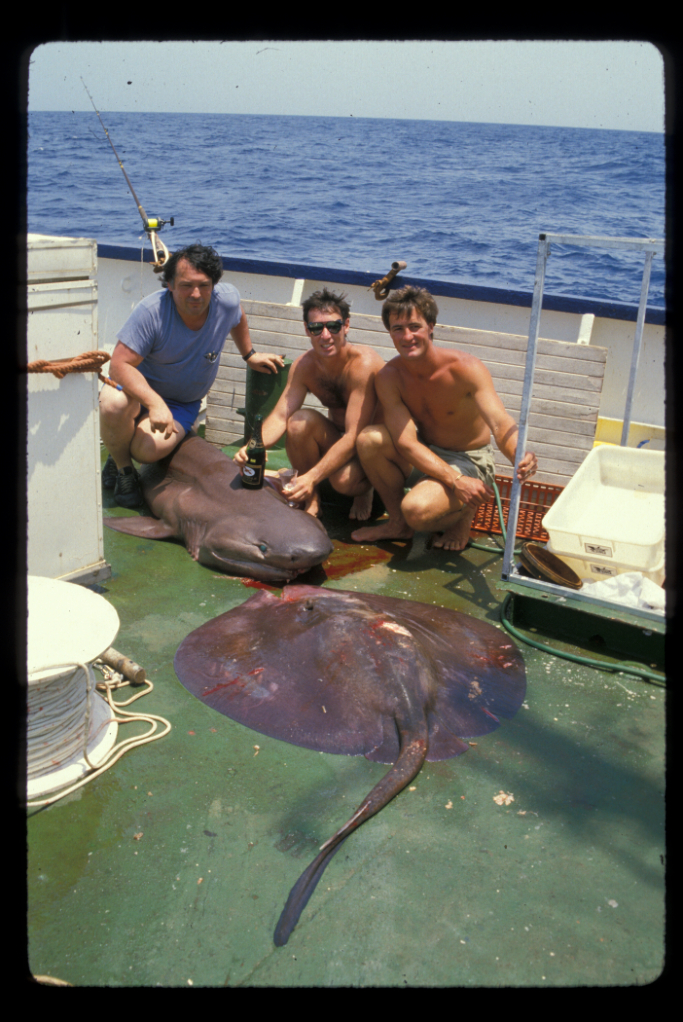

As a young graduate student in the early 1980s, I feel fortunate to have caught this wave of dynamic shark research that occurred. I feel fortunate that I was one of the early graduate students who came to Greg Cailliet’s Lab to study the life history and ecology of sharks in bay ecosystems in northern California. It was a terrific time to actually conduct fieldwork and learn just how complicated these animals are. I was also very fortunate to have met and or corresponded some of the most notable researchers at the time, such as Leonard Compagno, John McCosker, Don Nelson, John Stevens, Sonny Gruber, Perry Gilbert, Stewart Springer, Jack Garrick, Jack Casey, Frank Carey, Eugenie Clark, and many others.

As a footnote, Leonard Compagno was a consultant on the original Jaws movie and relayed to me stories of having worked on the original design of the mechanical shark, Bruce, with Steven Spielberg. If you watch all the way to the end of movie, Leonard is credited at the very end of the movie. I always thought that was kind of cool!

The 1980s and 90s saw an explosion in field studies on shark life histories and ecology. These studies lead to changing attitudes towards sharks with management policies and conservation measures eventually being implemented. The FAO in 1999 released their International Plan of Action for Sharks, which lead to dozens of countries eventually developing their own National Plans of Action.

For myself, I feel especially privileged to have been a participant through this evolution of shark research. Of equal fortune, I was not alone. A great cohort of collaborators and friends came of age as professionals during this exciting time. Many of us now have our own research labs and graduate students.

My early training under the tutelage of Greg Cailliet was ecology and life history based, but as I branched out into the world, spending time in Africa and Asia, I kept coming across shark species that did not seem to conform to current available regional keys, if one even existed. I often found myself working through piles of sharks gathering data, but was often skeptical of their identification. It was Leonard Compagno’s early recognition (and inspiration during my Ph.D. studies) for the need for shark conservation measures and the importance of knowing specifically what species are involved. Whether for research, fisheries management and policy, or conservation, it is critically important to know what species one is studying.

This early and informative background helped shape my own Lab’s research focus in our search for Lost Sharks! Over the past decade and a half, about 20% of all known shark species have been discovered and formally named. However, many more are still waiting to be discovered. One of these hot spot areas, and a focus of our research, is the Western Indian Ocean where we are still finding new species.

With many newly discovered species to be named, we are in the mist of an ambitious effort not only to name these sharks, but more importantly to share our passion for science through discovery and exploration, and to bring it to students through our outreach programs. Our recent naming of the Ninja Lanternshark (Etmopterus benchleyi) highlighted, an innovative interactive concept conceived and developed by my student Vicky Vásquez. It demonstrated just how kids could be inspired to participate in the scientific process.

It is hard to understate the importance that Jaws has played in bringing shark research to the forefront over the past 40 years. Shark research may eventually have come into its own without it, but from my perspective it was this movie that really put sharks in the public conscience. Despite the more publicized negative aspects, Jaws has actually been very good for sharks overall.

From my perspective, Peter Benchley’s real legacy is having brought the plight of sharks out of the shadows and to the forefront of public attention. Without his timely book and an exceptionally well-made blockbuster movie, shark management and conservation may never have come to light. The vast majority of sharks would still remain lost from the public’s conscience, with many suffering dire consequences!

If you would like to learn more about our search for Lost Sharks, and support our efforts, please visit our Experiment.com project page “Looking for Lost Sharks: An Exploration of Discovery through the Western Indian Ocean” to learn more, and please consider donating to our project.

Donations of $100 or more will received a limited edition print of a new species illustrated by Marc Dando, shark illustrator extraordinaire! You can see Marc’s work in the recently published “Sharks of the World”.

All additional funds received over the stated goal will go towards supporting Lost Sharks. We have a lot of sharks still to be named, so your support will allow us to continue our research. We will be posting Lab Notes on our project page of other new species we are working on.

We will be bringing our new discoveries to classrooms for school kids in communities historically underrepresented in the sciences. Your support will enable us to reach more classrooms this fall.

It is an exciting time to be a shark researcher. I mean, it does not get much better than the excitement of naming a new shark species!

Author’s note: The above article is a modified excerpt from his forthcoming book “Looking for Lost Sharks.”