When California resident June Emerson snapped a photo of her children playing at the beach, she didn’t expect it to generate international news. Although the kids seem to be adorable, that isn’t what captured the attention of the media. In a wave behind them, you can see the outline of a large animal swimming by (or being “terrifying” and “creeping up on them,” as the Daily Mail called it).

The media, including local, national, and international outlets, wasted no time in calling it a shark. However, as Jason Goldman wryly noted, “not all grey things with dorsal fins in the ocean are sharks.” This animal is almost certainly a dolphin. I asked a dozen shark scientists and a handful of dolphin scientists, and all quickly agreed that this is a dolphin.

As I’m no fan of merely appealing to authority (though I’ll trust someone with years of training over the painful to read comments on many of the news pieces), I’ll share with you how we can tell. First, let’s clean up and brighten the image. Since I am not a photoshop master, let’s borrow a cleaned up and enhanced image from KTLA.

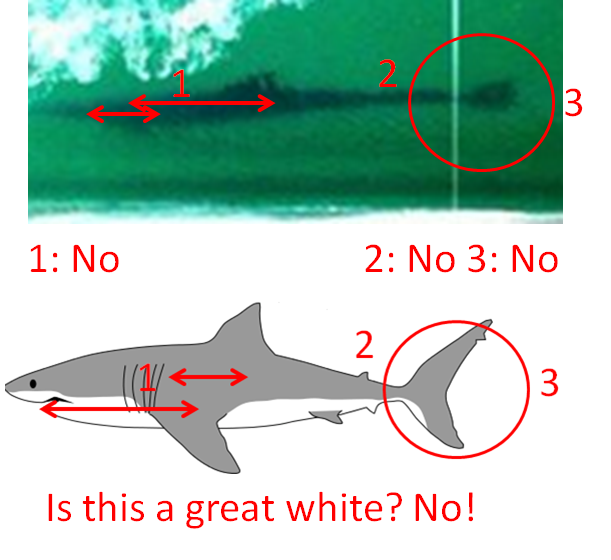

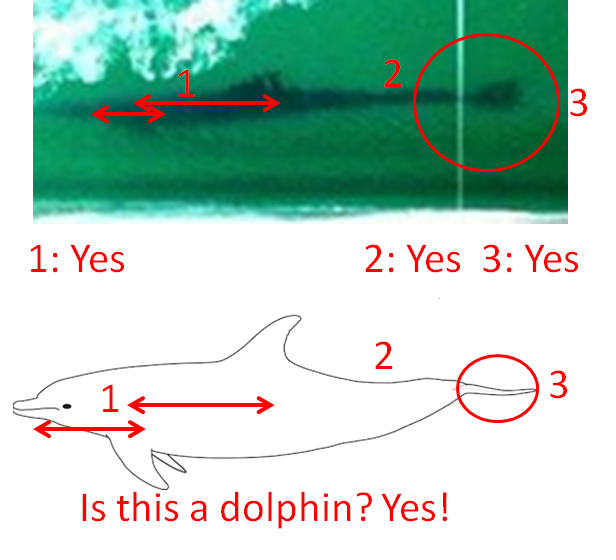

Even though the image is somewhat blurry (understandable, as June was trying to photograph her children and not the animal behind them,) there are still easily identifiable features that clearly show that this is not a great white shark, but a dolphin.

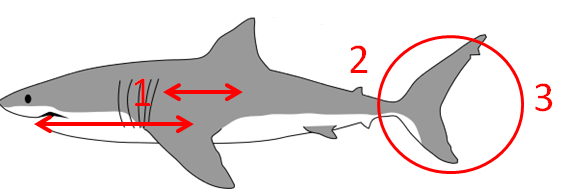

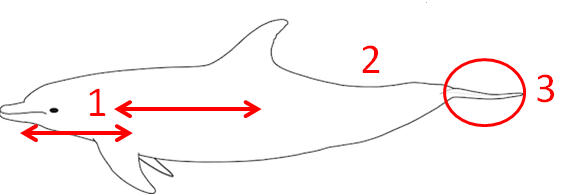

Lets compare the rough outline of a great white shark with that of a dolphin (images are from Wikipedia, H/T to Pete Thomas for finding them and pointing them out to me).

On a great white shark, the pectoral fins are relatively far from the head and relatively close to the first dorsal fin (#1) . Like all sharks, great whites have a second dorsal fin (#2). Like all sharks, great whites swim by moving their tail side-to-side (#3).

Though I used a side-view drawing for convenience, these features are all easily seen on the real thing.

On a dolphin, pectoral fins are relatively close to the head and relatively far from the dorsal fin (#1). There is no second dorsal fin (#2). Unlike sharks, dolphins swim by moving their tails up and down, resulting in a drastically different tail shape (#3).

Again, these features are all easily seen on the real animal.

So, now that you know what to look for, let’s compare June’s image with the features of a great white shark.

Now let’s compare June’s photo with that the features of a dolphin.

In a pseudo “debate” with me (we never actually communicated directly) for CNN, Shark Week producer Jeff Kurr noted that there have been a lot of juvenile great whites in this area. That’s absolutely true, and it’s a good sign for the conservation of the species. However, that’s hardly evidence that this is a great white. He didn’t note that there are also a lot of dolphins in the area, and that they’re often observed surfing in the waves.

The cynic in me can’t help but notice that many news articles noted within the text of the article that this could easily be a dolphin, yet hardly any used “dolphin” in their headline. It isn’t hard to imagine an editorial discussion along the lines of “eh, it may be a shark, it may be a dolphin, more people will click the link if it talks about a big scary shark near cute innocent children.” Though not exactly rare, this kind of fear-mongering “if it bleeds, it leads” journalism has had a significant negative impact on public perception of sharks, and by extension shark conservation policy, and by extension the population status of threatened species.

June and her children were in no danger, which also would have been true if the animal photo-bombing them was a juvenile great white shark. Many species of sharks are in danger, and sensationalist journalism such as much of the coverage of this “photobomb” does them no favors.

Good one. The truth is out there 🙂

I’m curious: is there a big difference in what dolphins and sharks can do more efficiently/faster/better than the other, based on vertical vs horizontal tail positions? It seems kind of interesting that two similarly shaped but distantly related animals developed two different solutions for swimming. Or in other words, is the tail positioning because sharks and dolphins are trying to do different things in the water (hover over the sea bed vs. cruising open ocean, maybe) or is it just two good solutions to the same problem of how to use a tail to push you forward in the ocean?

The tail alone was a dead giveaway.

One of the main differences would be due to their evolutionary history. Sharks have been in the water a long time, but dolphins ancestors evolved to come up on land then re-evolved to go to the water. They are trying to do roughly the same thing, but are starting from very different parts. My (educated) guess is that Sharks have maintained the lateral muscles required for the side to side propulsive tail motion. However, when the dolphin’s terrestrial ancestors moved onto land, they needed stronger ventral muscles in order to support their bodies in between their legs. This would lead to a greater ability to move a tail up and down when evolving back into an aquatic animal. Hopefully that helps.

Jonathan – I’m sure the shark expert will respond, but since I’m a paleontologist and my expertise is in evolution, let me start. Evolution always works with what it already has to work with. Fish, including sharks, evolved from side-side squiggly critters, while dolphins and whales, being mammals, evolved more directly from animals (some weird members of the pig family) that had their limbs under their bodies and could gallop. So it was a shorter pathway for mammals that were coming back to live entirely in the water to bring their up-and-down body plan with them, hence their style of swimming. And it works because it has been thought that the up and down swimming allows them to come up for air, and then back down more efficiently, which mamma;s need but fish do not, though his may not be all true. Similarly, right now we’re seeing a species of lizard, the Galapagos marine iguana, physically adapt for an aquatic lifestyle, and as you’d expect from his reptilian ancestors, they also wiggle from side-side.

The whole, “If it bleeds, it leads” method of media is problematic. It’s not helping educate facts, that’s for sure. I’m no great expert but even I could see that wasn’t a shark.

This is great! I’d argue the “at no risk” comment, though. Dolphins can be real assholes.

Another interesting thought to explore: If it WAS a shark, should those people even be worried?

I don’t know the answer to this question. But I’ve read that these whites are born around the South Bay of LA, and live there while young, then move on to other areas once larger. I think they eat small things like sting rays while in the South Bay. From what I understand, they aren’t large enough to care for human meals. The shark in that image looks to be 8 feet or so.

According to this site that tracks sitings, there were over 25 sharks in the Manhattan Beach area in 2013: http://www.sharkresearchcommittee.com/pacific_coast_shark_news.htm. I saw one myself while surfing a few months ago.

As far as swimming function and efficiency, I don’t think there would be much of a difference. Both sharks and dolphins are noted to be fast, efficient swimmers. I think a good difference is that dolphins and their “up/down” swimming mition probably accounts for the former terminal airway to be modified into a top of the head airway, nares or “blowhole”. Additionally, cetaceans have evolved to exchange their air with about 88% efficiency in 0.03 seconds. This shows a massive alteration from the land-dwelling freely breathing terrestrial quadropeds they formerly were. Dolphins are also constantly living in a complete stage of concious apnea…they must think for every breath. This is why they (also like sharks) have evolved to never fully sleep (one rest one hemisphere of their brains at a time).

Anyway, main difference between these successful marine predators is that one must surface frequently, while the other needs not surface at all.

Oh, and not to disagree with “Dave”, but the ventral muscles were already very well developed in artiodactyls prior to their move to the sea (to become dolphins and whales)…it was the massive increase in the muscles above and dorsal to the spinal column that had to be adapted. If you feel along a land mammal’s back you can feel their spine just inder the skin…this is not the case with dolphins and other cetaceans…those muscles are brand new (evolutionarily speaking) and account for much of the up-stroke of the swimming motion which in dolphins is known to be equally as important as the downstroke.