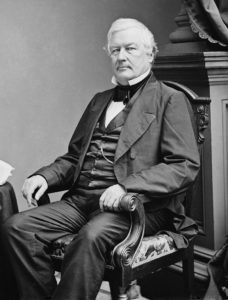

The numbers are in, and over the last eight years, President Barack Obama has protected more ocean than any other president in history. His expansion of NOAA and implementation of a National Ocean Policy will impact ocean health and fisheries management for generations. By almost any measure, he has had the biggest impact on the ocean of any modern presidency. Which raises the obvious question: is President Obama the most influential ocean president in history? Not by a long shot. That honor has to go to the president who’s policies have fundamentally shaped and reshaped how we view and control ocean territory, who laid the foundation for almost all the ocean protections we currently enjoy, and who set the precedent for the American Empire. That man is President Millard Fillmore, and he did it all for bird poop.

1850.

Agricultural science is beginning to understand that soil is not just soil, but a collection of nutrients that are slowly drawn from the ground by growing crops. Nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium are crucial ingredients. The Industrial Revolution is pushing agriculture away from passive crop re-nourishment processes and towards intensive, fertilizer-driven farming. Fertilizer producers can’t keep up. At the same time, the American whaling industry had reached its zenith and began to fall. Coastal whales were harder to find and the bold men of Nantucket ventured out across the Pacific in search of the last great whaling grounds.

In these voyages, the whalers found numerous tiny, often uncharted islands in the Pacific. These remote islands were refuges, not just for weary sailors, but for generations of seabirds. From these seabirds rose great mountains of guano, guano rich in the nutrients plants crave. Guano was the solution to the fertilizer crises.

In his first State of the Union, delivered soon after the death of Zachary Taylor from apparent food poisoning barely more than a year into his presidency, Fillmore declared that:

Peruvian guano has become so desirable an article to the agricultural interest of the United States that it is the duty of the Government to employ all the means properly in its power for the purpose of causing that article to be imported into the country at a reasonable price. Nothing will be omitted on my part toward accomplishing this desirable end.

Fillmore’s push for the government to pursue guano “by all means properly in its power” led to a boom in guano mining and ultimately the Guano Islands Act of 1856, which was signed into law by his successor, Franklin Pierce. The Guano Islands Act would set the stage for America’s expansion in the Pacific and beyond.

The Guano Islands Act establishes that:

Whenever any citizen of the United States discovers a deposit of guano on any island, rock, or key, not within the lawful jurisdiction of any other government, and not occupied by the citizens of any other government, and takes peaceable possession thereof, and occupies the same, such island, rock, or key may, at the discretion of the President, be considered as appertaining to the United States.

The Act allows US citizens to claim overseas islands, provided there are no other occupants or foreign claimants, mine the guano, and sell it within the United States as if it were a domestic product. “Appertaining” was the key term by which all other confusion emerged. Islands that “appertain” to the US weren’t fully part of the country. Over the next half century, the US would claim 100 guano islands to be mined and then, for the most part, abandoned. The most well-known of the guano islands was Midway Atoll, now a bird sanctuary, which played a critical role in the Pacific theater during the Second World War, but the US still maintains claims over 14 guano islands, three of which are currently in dispute. These include French Frigate Shoals, Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, Palmyra Atoll, and Swains Island. Baja Nuevo and Serranilla Bank are disputed with Columbia and Navassa Island, one of the few claims outside of the Pacific, is disputed by Haiti.

Navassa would be the site of the most important legal precedent to emerge from the Guano Act. Guano mining in the tropical heat is brutal, unforgiving work and, in 1889, the Guano miners of Navassa staged an uprising to protest the harsh conditions. Five supervisors were killed and the United States sent in warships to quell the rebellion. Eighteen workers were brought to Baltimore, tried for murder, and sentenced to death. But, before that, there was no precedent for who exactly had legal jurisdiction over guano islands. An appeal, funded by the Order of Galilean Fisherman, went all the way to the Supreme Court. In Jones v. United States, the Court ruled that the federal government did, in fact, have criminal jurisdiction over guano islands and upheld the lower court’s judgement. Fortunately for the miners, President Harrison commuted their sentence.

The Guano Island Act and the Jones decision set the precedent for what would later become insular areas and unincorporated territories, places that were and are part of the United States, yet do not enjoy full representation. Insular areas can be held by the federal government in perpetuity, without ever gaining the ability to obtain statehood. This established precedent for the United States dramatic expansion into the Pacific, which, at its peak, included both the Philippines and the Panama Canal Zone, as well as numerous Pacific islands, including Guam, the Northern Marianas, and American Samoa. On the East Coast, Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands are also unincorporated territories.

Curiously, Palmyra Atoll is an incorporated territory, which means that, despite being uninhabited and situated about 1000 miles south of Hawaii, Palmyra is considered an integral part of the United States, rather than an insular area. Palmyra is owned, almost entirely, by The Nature Conservancy.

Now here’s where things get weird. When the Guano Island Act became law, nations had claim over their territorial seas, an area that stretch from 2 to 6 miles from shore, depending on the country. Originally, territorial seas were set based on the range of the heaviest cannons, giving coastal settlements and cities the ability to defend themselves from warships entering their territory. This was later expanded to 12 nautical miles in the late 20th century and then, in 1982, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, established the 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone around all nations’ coastal holdings. Insular areas counted towards the EEZ.

Suddenly, those tiny islands weren’t so tiny.

An idealized guano island, barely more than point rising above sea level, in the middle of the Pacific with no nearby neighbors would have an EEZ with a radius of 200 nautical miles. That works out to 325,000 square kilometers, which is bigger than New Mexico. The United States currently has the second largest EEZ in the world (France, with similar colonial holdings has the largest EEZ, which currently encompasses 8% of the world’s oceans. Also, France owns an island entirely within Canada’s EEZ, which is weird). Today, the 11 undisputed guano islands contribute almost 1.2 million square kilometers to the total area of the United States. that’s larger than Texas, slightly smaller than Alaska, and a full 10% of the country’s total EEZ. And that’s just counting islands claimed directly through the Guano Islands Act, not islands like Guam, Samoa, Saipan, and all the insular areas whose acquisition was made possible by the precedent set by the Guano Islands Act.

It’s hard to understate just how important this act has been for ocean conservation. It has enabled, directly or via proxy, the protection of hundreds of thousands of square kilometers of ocean. It also, for good or ill, expanded the reach of the United States of America deep into the Pacific (literally. Through the EEZ around the Northern Mariana Islands, the US now controls the vast majority of the Mariana Trench).

One-hundred fifty years ago, President Millard Fillmore declared that we must pursue guano by “all the means properly in [our] power.” The vast territorial expansion that emerged from so simple a decree permanently reshaped the world’s oceans.

Hey Team Ocean! Southern Fried Science is entirely supported by contributions from our readers. Head over to Patreon to help keep our servers running and fund new and novel ocean outreach projects. Even a dollar or two a month will go a long way towards keeping our website online and producing the high-quality marine science and conservation content you love.

A huge thanks to Andrew Middleton, who worked out the areas for guano island EEZs.