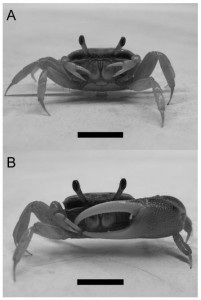

Imagine yourself a fiddler crab. For this exercise, imagine yourself a male fiddler crab. Are you with me? Great. Check out your right claw, it’s a sleek, slender machine, perfect for picking through the sand as you sift out bacteria and other microorganisms for food. It also makes a handy shovel for digging nice deep burrows to protect you from harsh conditions. Now check out your left claw. Wow! This thing is massive. If you possess a particularly vivid mind and have place your ego within the carapace of Uca panacea, your giant claw is more than a quarter of your body weight. This comically mis-proportioned appendage is why those pesky bipeds call you and your cousins “Fiddler Crabs”.

Imagine yourself a fiddler crab. For this exercise, imagine yourself a male fiddler crab. Are you with me? Great. Check out your right claw, it’s a sleek, slender machine, perfect for picking through the sand as you sift out bacteria and other microorganisms for food. It also makes a handy shovel for digging nice deep burrows to protect you from harsh conditions. Now check out your left claw. Wow! This thing is massive. If you possess a particularly vivid mind and have place your ego within the carapace of Uca panacea, your giant claw is more than a quarter of your body weight. This comically mis-proportioned appendage is why those pesky bipeds call you and your cousins “Fiddler Crabs”.

See that female fiddler crab at the perimeter of your territory? Yes, she is checking you out. That giant claw of yours is primarily used to attract mates, signalling to interested parties that your are fit and fecund. You even have a special dance, unique to each fiddler crab species, to announce your vitality. And if some other, lesser-clawed, male tries to move in to your territory, why, you’re equipped with a serious piece of hardware to drive off that interloper.

You’ve got a problem, though. That interested female doesn’t have a giant claw, she’s got two regular claws, claws that are good at collecting food, digging burrows, and generally being a crab. You giant claw means that it takes you longer to eat your recommended daily allowance of calories and, because you have this huge, energy draining thing hanging off your carapace, that, let’s face is, isn’t terribly useful for much other than attracting mates, you need even more food to meet your daily needs. Plus, you had to do all the claw waving to attract a partner in the first place. So while potential mates are well-fed and safely tucked away in their burrows, you’re still out on the tidal flats looking for food.

This is a risky place to be. On top of the many predators that like to snack on fiddler crabs, your tiny body is not good at retaining fluids and you run the risk of overheating and desiccating. Heat stroke and dehydration are bad news for just about any organism. Fortunately, you’ve already got the world’s smallest violin, and it’s good for more than just playing a sad song for all the dehydrated fiddler crabs.

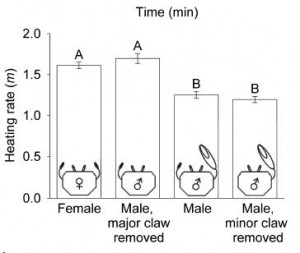

Pull you mind out of that hardened exterior for a moment and let’s talk about an elegant piece of science that was recently published in the austere journal American Naturalist. In “Thermoregulation as an Alternate Function of the Sexually Dimorphic Fiddler Crab Claw”, Darnell* and Munguia wanted to see if the male fiddler crab’s giant claw provided other benefits that would make it a slightly less ridiculous ornament. They performed a series of tests to measure crab response to heat for both male and female crabs. For the male crabs, they removed the giant claw from 1/3 of them, the tiny claw from 1/3 of them, and left the final third intact.

Become a fiddler crab again for a brief moment, and absorb the previous paragraph. You have a 2/3 chance that they are going to pull one of your arms off! Don’t panic. Fiddler crabs, like many other arthropods, have the ability to autotomize – or self-amputate. If a predator were to grab you by the claw, you could drop that claw yourself, along a pre-defined break plate, and scurry away while your predator snacks away on something that used to be you. A membrane will form along the break plate to seal of the wound, and over the next few molts, your claw will grow back. That’s a pretty useful trick (of course, if it’s your giant claw that you autotomized, you’ll be dining alone for the next few molting cycles).

Back to the science, Darnell and Munguia induced the crabs to autotomize one (or none) of their claws, then exposed them to a radiant heat source. Body temperature and body weight were measured every ten minutes. Body temperature of crabs with their giant claws removed and female crabs increased faster, and body weight decreased faster, than intact males and males with their tiny claw removed. This supports Darnell and Munguia’s hypothesis that the giant claw of male fiddler crabs plays a role in thermoregulation, as well as mate selection.

Back in you shell, you can rest easy in the knowledge that that giant claw of yours may force you to spend more time on the surface, but at least it also helps you regulate your body temperature and keeps you from overheating during those extra hours spent in the sun. And an autotomizing thermoregulator isn’t the only secret weapon at your disposal. Fiddler crabs can also change the color of their carapace to blend in with their surroundings and reflect heat.

All these tricks give you some advantage in the fight for survival, but the real fiddler crab secret to survival is your overwhelming numbers, so get out on that sand flat, wave your claw in the air, and get to know your neighbors.

Darnell MZ, & Munguia P (2011). Thermoregulation as an alternate function of the sexually dimorphic fiddler crab claw. The American naturalist, 178 (3), 419-28 PMID: 21828997

*If Dr. Darnell sounds familiar, it’s because previous to becoming in-doctor-nated, he was the lonely grad student that lived on my boat in the middle of Onslow Bay for several weeks while tracking blue crabs. This was his home.

My take on this paper:

http://neurodojo.blogspot.com/2011/08/tuesday-crustie-cool.html

What became of the males whose minor claws were removed for the experiment? Presumably because fiddler crabs require their minor claws for feeding themselves, and because the severed appendages grow back over several (annual?) molts, those poor little crabbies must have died off shortly after the experiment. Did you at least make a tasty meal of them to honor their contribution to science?