Say your local Lions Club wants to hold a focus group to determine what the community thinks would be the best way to direct community service efforts? What if you, as a blog writer, want to survey your readership about their demographics? What if the local food group wants to stand in front of a grocery store surveying people where they get their food from? What if an independent scholar wants to interview people for their next book? These are all real-world applications of social science that may have significant positive impacts to the community involved. But are they responsible to anyone for ethical behavior? Should they be? If they were University scholars, they’d be subject Institutional Review Board oversight. No IRB approval means no publishing and no funding.

Even in the university setting, what if a scholar decides to cross disciplines and use some social science methods? Are they subject ot IRB review? Say fisheries biologists want to interview fishers about their knowledge of fish stocks and aggregations or an agricultural extension agent wants to survey local farmers where they get their seed? The what-if’s could go on forever. And they are all in the ethical grey area.

I’m not saying IRB is perfect. Let’s start with that. Every social scientists knows just how to write them to not raise any red flags and how methodological details can be tweaked to not cross the threshold of a full review. There’s little enforcement that you’ve followed your own ethical guidelines promised to the IRB. There’s also a million ways you could be unethical that aren’t covered in the IRB application. But the process of getting and IRB review makes you stop and think about research ethics and that’s always a good thing. They set the bar for which we should all strive to fly far over.

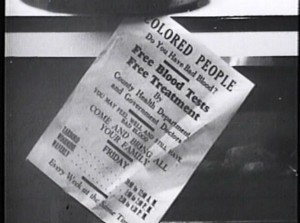

For those of you not familiar with the IRB, the concept was founded after Nazi soldiers were convicted of war crimes for experimenting on their Jewish captives (see longer history here). The Nuremberg Trials sentenced the Nazi soldiers and established the very basic baseline of informed, voluntary consent to participation in human-subjects research. A large portion of human subjects research is medical, so the initial ethical code was directed towards medical research. In the US, the most egregious example of ethics violations occurred with the Tuskegee trials, where African-American men in the South were told they were receiving syphilis medication while the doctors were really dosing placebos and monitoring the progression of the disease for 40 years.

Over time, The Belmont report added further criteria beyond the basic medical “do no harm” – experiment participants must be respected, there must be benefits, and burdens of the research are distributed justly. Modern IRB applications focus heavily on enumerating the potential benefits and risks participants will be shouldering.

Ok, so let’s go back to the basic social science methods – interviewing, participant observation, focus groups, and surveys. The potential risks and benefits are not remotely on the same scale as those involved in medical research. Most of the time, these types of research are exempted from full review. But IRB specifically protects vulnerable populations: prisoners, children, pregnant women, and indigenous peoples’ knowledge. All of these are on the list because they have been historically wronged.

So let’s get back to my original question – who should be subject to IRB oversight? The IRB is well-intentioned if at times bureaucratic, and entirely in response to serious breaches of personal ethics. Yet only medical students and social scientists are told during their training what IRB is and why we need to adhere to the professional practices that IRB encodes. Those outside of the ivory tower not only may not know that IRB exists – but cannot have access to it even if they wanted to. I don’t have an answer to this tough question, but I’ll leave you with two vignettes of my own experiences that have made me think deeper about research ethics in an age where social science is a more well-loved discipline.

Citizen science ethics

Envision a group of citizen scientists who love botany. They decide to get involved in something like Project Budburst where they monitor local plants for flowering times, pollinator activities, and abundance and distribution of said plants. Most of the volunteers are retirees looking for a little extra excitement in their day. There are teachers who sign their classes up as a way to collect real scientific data in the classroom. Their data goes to an online portal so any and all can access it and interpret at will. There are a couple scientist facilitators running the program to answer questions, provide training, monitor data quality, and organize events to keep the volunteers motivated.

Citizen scientists are inherently volunteers and the field is built upon an ethos of respect for contributions of non-scientists. Most projects give good data, environmental education, and fun back to the communities that participate. Risks are evenly distributed among participants and scientists. So they meet the Belmont report standards. But after the initial hurdles of establishing such a program, real ethical issues emerge.

The scientist facilitators want to publish on the data. But can you publish with 5,000 co-authors for all the people who contributed to data collection? If not, then how else do you give them credit? And do you own that data anyway – or should you be asking permission from the group to do something with it? Perhaps more fundamentally, how do you make sure that the analyzed and interpreted results make it back into the hands of those creating the data in an era of journal paywalls and expensive subscription fees? How can you promise open-access without the $3000 in the budget to pay for that priviledge?

Many citizen science projects come and go without much program evaluation. So it behooves the facilitator to solicit feedback in some form from the participants and perhaps track both scientific and participant outcomes over time. This is straight-up social science. It involves children, who participate every year with their class. You want to publish these results so you need an IRB approval number – but many, if not most, citizen science projects are not affiliated with a university. So now what? Citizen science groups seem to be aware that they need help with evaluation and that often comes from universities, with the added bonus of the IRB. But is that the only solution?

Finally – and perhaps the most perplexing – some of the plant data submitted by participants GPS tag the location of critically endangered plant species that have a high value on the black market. The citizen science group decided at their organizing committee meeting that they wouldn’t post this information on their online data portal for the sake of the plant’s existence. But how do you ensure that the revolving door of volunteers and facilitators with access to the full data set don’t use the location information to gain some extra cash? How do you protect landowners whose property houses this valuable greenery?

This year at the Public Participation in Scientific Research conference, an ethics breakout group decided the field needed an IRB-like but more all-encompassing set of ethics. Something like IRB combined with the anthropological code of conduct, that sets out expectations and suggestions for how to protect participants and their hard-earned data.

The Interdisciplinary Thinker

You’re a fisheries biologist in graduate school working on stock models with the aim of improving fisheries management. You’ve had a 4-year undergraduate education that introduced you genetic methods, stable isotopes, and more statistical methods than you care to think about. In graduate school, though, you realize that the fishermen in your community have a wealth of information gathered over their long careers about behavior of the fish and how the fish stocks fluctuate with environmental variables from year to year. You’re interested in including them in your food web models and that involves getting lots of data about their catches and behavior. Perhaps you’re also interested in how the public perceives the state of fisheries management and are curious if your outreach efforts through twitter and your blog are actually having any effect. Answering your question is going to take surveys, interviewing, and perhaps focus groups.

Recognizing you don’t have the training in survey writing or interview technique, you ask a social science friend for help designing your tools. You appropriately try out your questions on other friends to make sure they make sense and that you’ll get data you can actually statistically analyze when you’re done.

However, when you get in the field, the fishermen are leary of telling you what they caught – and even more leary about telling you what bycatch they’ve captured. That shark they caught on a tuna longline and let go, not sure if it was alive or dead? They probably don’t want that getting reported to a state agency with the power to arrest them or take their license. Or they don’t want a picture of them removing a (healthy) turtle from their pound nets showing up on that blog of yours where the “crazy environmentalists” will find it. They ask you if they’re speaking confidentially, off-the-record. How would you answer them?

IRB would tell you there’s no such thing as true confidentiality. Anyone who knows the community well enough can probably guess who’s out pound netting and willing to talk to scientists. A best effort at confidentiality is all any of us can give. Even people in the witness protection program occasionally get found.

So what training should be offered or required for these disciplinary-busting endeavors? Should IRB be required training for all researchers, even those with tangential social interests? If not, how do we ensure that participants are protected? Local ecological knowledge has been one of the hotbeds of intellectual property theft over the years, so I’d argue that current practices aren’t enough.

I’d encourage all researchers out there to sit back for a minute, take a deep breath, and think about what research ethics means to you. If there are people involved in your research (and I’m sure there are), what are you responsible for?

Amy, great article.

I just sent this to my entire Ph.D. program.

In Fredericton, Canada, we are organizing an ethics summit to explore alternatives to formal research ethics review. It will take place 25-28 Oct. 2012. We have scholars; coming from the USA, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and the United Kingdom. If you are interested in coming, please consult our URL:

http://wp.stu.ca/ethicsrupture/

Amazing blog mate

This is a great article. Although I’m no longer active in academic research (and when I was, I was working with rats and cell cultures), it made me think. It made me think about how I use all the knowledge I learn from other people, which I use for my website and everything related to my project Amocean. I don’t have any answers, but thanks for this push, for putting something in front of my eyes again, that had moved out of sight.