If you have ever dealt with scientific data, you’ve probably encountered one of the shadier sides of science: academic publishing. While they’ve stood, in some cases, for centuries, as the official record of scientific advancement safeguarded under the watchful eye of peers, modern journals live in a modern world. Millions of words have already been spilled on the subject, so that’s not what this article is about. Instead, I’m left asking whether academic publishing is the only means of getting the stamp of peer-review these days?

The reasons leading me to ask this question are many, but primarily through working in a management arena lately. One example, in particular, highlighted many of the disconnects between the need for verified scientific data and the incentives of journals. This moment was at a Chesapeake Bay Program Sustainable Fisheries Goal Implementation Team meeting (for those of you not in the Chesapeake region, that’s a consortium of regional fisheries managers), where a room full of decision-makers needed a verified stock assessment of blue crabs to move forward with their management planning. Peer-review is the time-tested, well-understood, and arguably easiest means of verifying data.

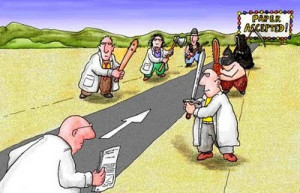

They needed that stock assessment yesterday, and the pace of academic publishing just doesn’t fit that timeframe. I feel for the editors that have to ask 10 different reviewers if they will read an article, and then pester two of them to turn in reviews while doing all the stuff they actually get paid to do, but each step in that process is at least a couple of weeks, so the year creeps on. While some journals are attempting to tighten their timelines, the culture of academic publishing is one of molasses, and culture is a very hard thing to change.

Back to that stock assessment – for those of you not in the fisheries world, it’s basically a count of the number of blue crabs in the Bay, split up by age classes and sex. It allows us to feed a fisheries model and predict what next year’s possible catch might look like. It’s VERY important information, but basically the opposite of sexy science. It’s not even new – these assessments are done every year or so, depending on the reproductive cycle of the focus species. The methods have been the same for decades, and should remain so in order to enable comparisons between the past and now. But these traits are basically the opposite of what journals are looking for – revolutionary new science that pushes the field forward. In these cases, editors will toss a manuscript before sending it out for peer review because it “doesn’t fit the journal”. However, sometimes science is done not to push science forward but to better inform society. This is one of those times.

In this case, the fisheries world already has a few avenues to find peer review outside academic journals – namely, agency technical reports and technical advisory committee reviews. Both of these forms of peer review focus on the quantitative and statistical aspects of the stock assessment to make sure we have the best numbers possible to help inform fisheries models and decision-making arenas. Many times, these kind of reports have minimal storytelling and outside context included, unlike journal papers, because the data just needs verification before going to a dedicated use. Everyone knows the context already. This is a great solution, but people aren’t as familiar with the review process and therefore sometimes don’t trust it as much as a journal article.

In addition, outside the stock assessment world, these kinds of avenues are more rare. In addition, academic publishing may not be rewarded for some careers or scientist roles as it is in academia, but can be a considerable investment in time. Think of citizen science groups with a volunteer base of scientists who want to contribute data to help some scientific issue move forward but may not have the time, skills, or desire to spend time writing an academic manuscript. They often find a data portal with some kind of review process as their final product. Or think of other scientific issues in need of a rapid response, like the sighting of a new or spreading invasive species or spread of a disease. By the time a journal article about gypsy moth spread comes out, entire forestlands may have been eaten.

I’d encourage everyone, in their efforts to make science more inclusive, to remember the many reaching arms of science into wide-ranging aspects of society, and peer-review has an important role to play. It just needs to come in a different format to fit the situation.