Our world is facing a biodiversity crisis so severe that many scientists have labeled it as the sixth great mass extinction in Earth’s history. Conservation efforts to date have focused on endangered species and “biodiversity hotspots” , relatively small areas with large numbers of species. Most of these hotspots are in areas you’d expect them to be, places like coral reefs and tropical rain forests. One surprising biodiversity hotspot is New Zealand.

Our world is facing a biodiversity crisis so severe that many scientists have labeled it as the sixth great mass extinction in Earth’s history. Conservation efforts to date have focused on endangered species and “biodiversity hotspots” , relatively small areas with large numbers of species. Most of these hotspots are in areas you’d expect them to be, places like coral reefs and tropical rain forests. One surprising biodiversity hotspot is New Zealand.

Though New Zealand is best known for it’s two largest islands, the country has over 700 islands larger than one hectare. Additionally, New Zealand is isolated- hundreds of miles of Pacific ocean separate it from Australia, and it’s farther still from Asia or South America. Similar to the Galapagos, this isolation has led to an extremely high rate of “endemic” species, plants and animals that are native to an area and aren’t found anywhere else on Earth.

New Zealand is particularly famous for its unique birds. You may have heard of the kiwi, a word which has become slang for a New Zealander*, but this nation is also known as the “seabird capital of the world“. In total, there are more than 60 endemic bird species found there.

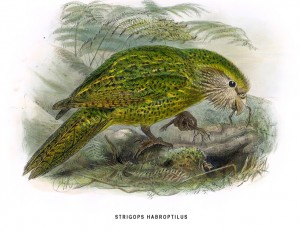

One of these endemic birds is the Kakapo, the world’s largest parrot. Flightless and nocturnal, these amazing birds live in forests. Like many of New Zealand’s birds, they are threatened by invasive mammal species such as rats, cats, and stoats (weasel-like creatures). Having evolved in an environment without these animals, the native birds are defenseless against them. Kakapo populations were devastated- down to just a few dozen animals individuals in the entire world.

New Zealanders have earned their reputation as one of the most conservation-friendly nations on Earth, and they wanted to help, but existing conservation strategies were useless to save the kakapo. Passive conservation (National Parks, marine protected areas, etc) focuses on limiting human influence and letting the natural balance restore itself. Using passive conservation strategies would have resulted in the extinction of the Kakapo. Something much more radical was needed.

It’s basically impossible to eradicate invasive mammals from an area as large as New Zealand’s main islands. However, the smaller islands (recall that there are over 700 of these) are much more manageable. Dedicated conservationists and government scientists began a campaign to eradicate invasive mammals from a small island in the 1980’s, and they were successful! The kakapos were moved to a new home free of rats, cats, and stoats.

That last sentence constitutes what was at the time one of the most radical conservation strategies in the history of human civilization, so it’s worth repeating. Managers didn’t declare native kakapo habitat a national park and make it illegal to hunt them, or illegal to develop the area for humans. Instead, every single kakapo in the entire world (at the time, there were 65) was caught, removed from their native forest, and transported to a small island whose ecosystem had been modified just for them. The species was saved from extinction, and “active conservation” was born.

2011 was a sad year for kakapo conservation, because both Richard Henry (then the world’s oldest kakapo) and Don Merton (a researcher instrumental in creating the phenomenally-successful kakapo recovery programme) passed away. Despite that, things are looking up for the species. 11 fledglings were born in 2011, bringing the world population to 129 spread over a few isolated (and protected) islands. A dedicated research team closely monitors their health and numbers, even influencing their sex ratios (with kakapos, the quality of diet right before mating determines whether male or female nestlings are born). Thanks to radio collars, scientists know exactly where every single kakapo on the planet is at all times, and all of them have names.

Kakapos are an amazing species not just because of their biology, but because of the incredible lengths that New Zealanders went to in order to conserve them. Thanks to revolutionary active conservation techniques, which have since been implemented for other endemic New Zealand birds and for other animals around the world, future generations may get to see the world’s largest parrot.

* New Zealanders became known as Kiwis during World War One, when British soldiers in the trenches with them noted that they use Kiwi-brand shoe polish. The logo was, of course, a Kiwi bird.

REFERENCES

Clout, M., Elliott, G., & Robertson, B. (2002). Effects of supplementary feeding on the offspring sex ratio of kakapo: a dilemma for the conservation of a polygynous parrot Biological Conservation, 107 (1), 13-18 DOI: 10.1016/S0006-3207(01)00267-1

Clout, M., & Merton, D. (2010). Saving the Kakapo: the conservation of the world’s most peculiar parrot Bird Conservation International, 8 (03), 281-296 DOI: 10.1017/S0959270900001933

Elliott, G., Merton, D., & Jansen, P. (2001). Intensive management of a critically endangered species: the kakapo Biological Conservation, 99 (1), 121-133 DOI: 10.1016/S0006-3207(00)00191-9

Lloyd, B., & Powlesland, R. (1994). The decline of kakapo Strigops habroptilus and attempts at conservation by translocation Biological Conservation, 69 (1), 75-85 DOI: 10.1016/0006-3207(94)90330-1

Myers N, Mittermeier RA, Mittermeier CG, da Fonseca GA, & Kent J (2000). Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature, 403 (6772), 853-8 PMID: 10706275

I hear about this and other “active conservation” programs and have to wonder if they really are a solution or the just the end result of species-based conservation movements. The recent red wolf recovery program comes to mind – red wolves have been extinct in North Carolina for several decade, despite it being part of their native range. They were recently reintroduced in a controlled setting where every member is tracked, and interaction with local coyotes and other large mammals is precluded.

In my mind, when you’re creating an exclusionary zone to protect a specific group of individuals, restricting their range and ecologic interactions, that’s not a conservation program, that’s a zoo. Since you’ve already stated that removing the invasives from most of the kakapo’s historic geographic range, what’s the ultimate goal of kakapo conservation? Just to have a few hundred individuals for posterity? Is there a plan for reintroduction? “Active conservation” doesn’t address the dominant problems facing an ecosystem, ignores the less charasmatic, less abundant, or undiscovered flora and fauna, and shifts the focus from ecosystem to species.

Just because the Kakapo is now securely isolated from its problems, doesn’t mean Tibbles isn’t still at large.

Good points all.

I’m a big believer in conserving whole ecosystems and not just charismatic species, but I found the revolutionary strategy that the New Zealand Department of Conservation used to be fascinating. In the meantime, these dramatic efforts to protect individual critically endangered species raise awareness, and can have the effect of creating “flagship species” (protecting whole ecosystems in order to save native habitat for the critically endangered species).

The ultimate goal of “active conservation” and “emergency conservation” is to make sure that critically endangered animals don’t go extinct before we come up with a bigger solution. The Department of Conservation people I talked to are hopeful that Kakapos can eventually be reintroduced to parts of their native range, but believe that creating those conditions can take a very long time. In the meantime, they are trying to keep Kakapos from going extinct.

I’m sure we can all think of alternative conservation problems that can benefit from the financial and personnel resources that are going into protecting 129 birds, but given that New Zealanders wanted to save Kakapos from extinction, I admire their creative solution.

You all have probably read it, but if not, this is a well written book that covers the history and controversy of the kakapo and other species conservation campaigns.

http://www.amazon.com/Rat-Island-Predators-Paradise-Greatest/dp/1608191036

I admire your wide-eyed optimism, but there are some critical flaws in the concept, and I think you need to be more realistic about the limitations of this approach.

What you’re proposing is removing an entire species (or, as is the case, several endangered species) from an ecosystem, achieving, through conventional conservation and management programs, a stable ecosystem in an altered state (either through resilience to introduced species or the management and removal of the invasives), and then reintroducing the “flagship” species back into what is now a fundamentally altered ecosystem. By removing the kakapo for several generations, you’re turning it into a non-native species.

It’s not about resource allocation, it’s about the fundamental ecologic implications of conservation in absentia.

It’s actually the same issues I addressed in better conservation through cloning – http://www.southernfriedscience.com/?p=12114.

Are you guys familiar with any of the books mentioned in this article?

http://www.washingtonpost.com/national/health-science/spaceship-earth-a-new-view-of-environmentalism/2011/12/29/gIQAZhH6WP_story.html

I don’t know if this is what the authors of any of those books mean to say but what I took away from this was that although the reporter uses the metaphor of a spaceship, you could also say that we’re at the point where we kind of have to manage the whole planet like a zoo. Never mind just one little island.

What seems to be missing here in the discussion is the inevitability that kakapos will certainly go extinct without these efforts. Should the Kiwis choose to use their national resources to protect this essentially relict population, rather than say a new naval ship, then who am I to argue?

I agree that it’s not an optimal strategy, but it’s now one of pragmatics — no-one’s going to seriously suggest an “eradication” of sorts for humans within the historical kakapo range. Given this, then perhaps there’s indeed something to be said for establishing such islands of (more or less) natural ecosystems physically separated from ecosystems irrevocably changed.

I think this kakapo story helps to remind us that an effective conservation strategy must always include some sort of “active” component to it. By the way, to me most strategies should be directed to the ecosystem level and to mantain it’s good functioning. I think it’s entirely possible, because we are dealing with islands here, to completely restore this areas to a historical level where the kakapo has a place on it (the costs and feasability may hamper this iniciative or not). The point is to always look to the big perspective.

First off, I’d like to say I’ve enjoyed these postings and the intellectual stimulation it’s provided! I hope my posting can contribute likewise. I highly recommend reading Chris Thomas’ 2011 TREE paper (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2011.02.006), he makes a great point that ALL ecosystems are altered from the state under which its inhabitants evolved in, largely due to anthropogenic effects. Even if humans haven’t settled there and introduced species such as rats and domesticates, global warming has increased the earth’s temperature and affected ecosystems everywhere. This includes species moving to locations they’ve never inhabited before (e.g. shifting to higher elevations, different latitudes), so translocating species to a location they haven’t previously inhabited before isn’t necessarily as artificial as it may seem given the current context. I think he presents a great argument for active conservation, namely that it’s impossible to totally return to some sort of natural, historic state.

Of course there are gradations of active conservation, and it can be argued that intensive ones are a waste of resources. I can see the point that most conservation programs are aimed at charismatic megafauna and are species oriented. This doesn’t mean that there aren’t cascading effects that can benefit the ecosystem, especially when you’re dealing with a keystone species such as a top level predator – see the uplifting manuscript on wolf reintroductions into Yellowstone http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2011.11.005 . It might seem ‘unnatural’ to reintroduce a species that’s been absent from a habitat for decades, but the species within that environment evolved to cohabitate under arguably monumental amounts of time; not performing the reintroduction could be seen as more ‘unnatural’ and unbalancing to the ecosystem.

I wouldn’t discount public support and pride for a species, there’s evidence across multiple taxa that this can be key in whether conservation programs are successful or not. I would argue that it’s more difficult to get people engaged in whole level ecosystem conservation than just a single species. If the kakapo is a source of pride for New Zealanders, than its conservation can be seen as a step in the right direction in educating people about conservation. Look at how controversial the North American pipeline is, it’s difficult to convince Americans that the pipeline is detrimental to our ecosystems, but I’d be willing to bet that if the bald eagle were down to kakapo numbers, even conservatives would be willing to allocate resources to preserving a bird of national pride.