A few weeks ago, Mark Powell at Blogfish posted “Where are conservation success stories?” in which he asks if we have a bias against good news in conservation. Late last year we presented a series of conservation success stories from the IUCN. Whether because we choose to focus only on the doom-and-gloom news stories or because the natural world really is in pretty bad shape, success stories in conservation are few and far between. That is why The Death and Life of Monterey Bay, a new book by Stephen Palumbi and Carolyn Sotka, is so important. Palumbi is a working scientist and director of the Hopkins Marine Station in Monterey Bay and his work has been cited on this blog before. Carolyn Sotka is the project coordinator for COMPASS, an organization that connects scientist to policy makers and journalists.

A few weeks ago, Mark Powell at Blogfish posted “Where are conservation success stories?” in which he asks if we have a bias against good news in conservation. Late last year we presented a series of conservation success stories from the IUCN. Whether because we choose to focus only on the doom-and-gloom news stories or because the natural world really is in pretty bad shape, success stories in conservation are few and far between. That is why The Death and Life of Monterey Bay, a new book by Stephen Palumbi and Carolyn Sotka, is so important. Palumbi is a working scientist and director of the Hopkins Marine Station in Monterey Bay and his work has been cited on this blog before. Carolyn Sotka is the project coordinator for COMPASS, an organization that connects scientist to policy makers and journalists.

In The Death and Life of Monterey Bay, Palumbi and Sotka present the history of Monterey Bay, from discovery, to exploitation, to collapse, and ultimately to rebirth. They weave the narratives of many important players, exploring the legacy of a dedicated conservationist who existed before the term was coined, the hunters, fishers, and canneries who found fortune and destruction, the writers and scientists who made Monterey Bay a literary icon, and the Bay itself, which survived by equal parts luck, tenacity, and foresight. The events in the book span hundreds of years, but we can still glean lessons from both the collapse and rebirth of Monterey Bay.

The Ruin

In the first section, Palumbi and Sotka lay out the initial causes that began Monterey Bay’s spiral into ruin. Prime among the the events that led to the ruin was the exploitation of sea otters for their pelts. The collapse of the sea otter population, and the subsequent cascade effect that decimated the kelp forests, has been well documented and continues to be studied today. Cascade effects have been observed all over the world, including in my own backyard, coastal North Carolina. Here, the declining shark populations has resulted in an abundance of cownose rays, which has been hypothesized to contribute to the decline of the NC scallop fishery. Unfortunately, we rarely know what the effects of removing a species from an ecosystem will be until it is already too late.

The Bottom

As we reach the bottom, an ecological dark age for Monterey Bay, where canneries dot the landscape, overfishing is rampant, and the water is rich with the discarded offal of processed fish, we find a glimmer of hope. Julia Platt was an accomplished embryologist who moved to California in the early 20th century and rose to become the mayor of Pacific Grove. Although she served during the darkest days of Monterey Bay, she laid the foundation for its eventual rebirth by establishing some of the first marine protected areas in the world. They were small, but they were the beginning of something greater. Beyond the protected areas, she also wrested control of the shoreline from the state, and gave the town of Pacific Grove control of its own ocean front. At her death, she was buried at sea.

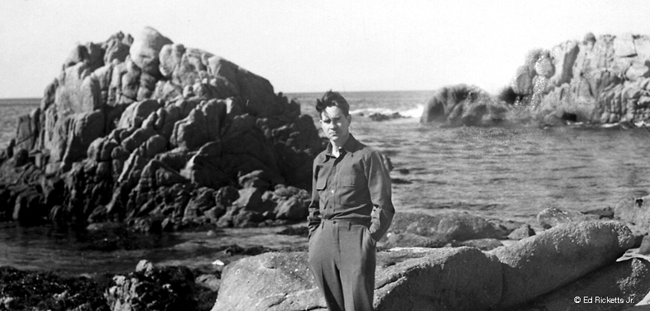

Then came the Depression, and with it a literary legacy that would burn Monterey into the collective consciousness of America. It was John Steinbeck, Joseph Campbell, and the great American tide pooler, Ed “Doc” Ricketts. Even as the canneries died a slow death of economic depression and overfishing, as the sardine fishery collapsed under the weight of nets and the oscillating Pacific, they transformed Monterey into a monument to the American spirit. But though Monterey was now steeped in culture, it was, in so many ways, a depauperate bay.

The Recovery

The otters came back first, and they brought with them a rejuvenated bay. The cascade effect that destroyed the kelp forest also brought them back. Many elements came into play, including Julia Platt’s marine reserves, the end of the canneries, the collapse of the sardine fishery, Cousteau’s aqualung, Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, and a new sense of environmental stewardship. At the forefront of all this was the creation of the Monterey Bay Aquarium. Here I must disagree with Palumbi and Sotka’s conclusions. In the final chapters they hold up the Monterey Bay Aquarium as leading the charge to renew the bay, but the reality seems much different. Economic, ecologic, and human elements had coalesced to bring the bay back to life. It was not the presence of the Aquarium that instilled an ocean ethic, but a renewed ocean ethic that inspired the Aquarium’s creation.

I love aquarium’s almost as much as I love the ocean, but the reasons they give to criticize the National Aquarium in Baltimore and the New England Aquarium in Boston, are the very reasons I find these places so compelling. The exhibits of the the grand East Coast aquariums are windows into distant shores. They allow us to glimpse places few have the means to witness. In the National Aquarium in Baltimore, you can wander through the Amazon jungles. In the New England Aquarium you can stare up in awe at a massive coral reef. The Monterey Aquarium is equally magnificent, but how could it hope to compare to Ed Ricketts’ Great Tide Pool, which lies just outside?

What can we learn from the collapse and subsequent revival of Monterey Bay? The tenacity and dedication of a few can drive massive changes. Even tiny steps towards preservation, such as Julia Platt’s 11-acre marine reserve can be the difference between recovery and collapse. The natural world is deeply connected and constantly in flux. There is always hope.

It is impossible to predict what the long term impacts of our action will be, which ecosystems are resilient enough to recover, and which are not. But planning, vision, and, most of all, passion, can help to instill a stewardship ethic in the next generation. Education must be central to these goals whether it be by tide pool or aquarium. Palumbi and Sotka have tied together Monterey Bay’s legacy and given us a model for what, with equal parts luck, passion, and perseverance, might be.

The book review for “The Death and Life of Monterey Bay” is thoughtful and interesting. Thank you for including it.

Too bad we needed to have a student from across the continent to recognize the importance of Monterey Bay!

Great review! It’s important to have these success stories every once and a while, not to give the impression that the natural world isn’t in rough shape, but to show that our efforts are not in vain. On another book-related note, I just finished a biography of Ed Ricketts, titled Beyond the Outer Shore. It was a great read, and gave an interesting account of the collapse of fish stocks and rise of marine ecology on the West Coast.