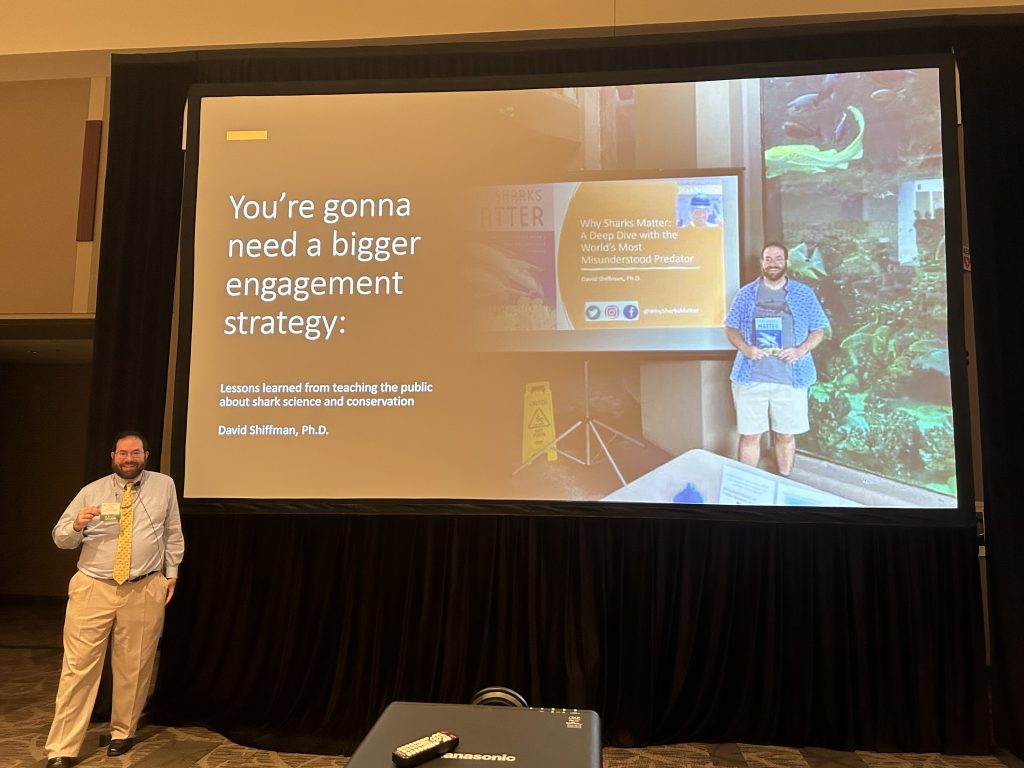

In January 2024, I presented the John Moore Lecture at the Society for Integrative and Comparative Biology conference.

The aim of the Moore plenary is to offer the society a new perspective on science education, and my talk was entitled “You’re Gonna Need a Bigger Engagement Strategy: Lessons Learned from Teaching the Public About Shark Science and Conservation.” It focused on my experiences with public science engagement through social media, writing, and public speaking, as well as training other scientists (over 1,000 so far!) how to do these things.

Many of these lessons were taught to me, implicitly or explicitly or through example, by others too numerous to name and thank over the last 15 years or so. Many are hard-won lessons learned by doing this badly. And while I try to include as much “do this for good outcomes” as “don’t do this or there will be bad outcomes,” far too few are strategies for an easy and high-impact win.

Additionally, the proverbial soup that I swim in concerns endangered species conservation policy, which has different goals, different opponents, and different ways of convincing the public than other branches of science—I would never, for example, claim to be an expert in communicating concepts related to public health, a really important area of science communication.

As always, I am happy to answer serious questions asked in good faith.

Lesson #1: Public science engagement is good for science, good for the public, and good for you… when done effectively.

Put simply, it matters what our non-scientist neighbors know and think about science and evidence and expertise, and their role in society and decisionmaking. We live in the community too, and what happens there affects us. Who our neighbors vote for doesn’t just affect our grant funding, but the survival of wildlife and wild places, and what states are unsafe for our colleagues to live and work in.

Also, we are privileged to get to devote our lives to questions about our world that fascinate us, and I believe that we have a duty, in general, to give back to the communities that make it possible for us to do that.

That doesn’t mean that “every scientist should have to talk to the public,” it doesn’t mean that you have to drop everything whenever any member of the public demands your time, and it doesn’t mean “public science engagement is easy and anyone can do it!” Instead, it means that public science engagement should be more highly valued by the scientific community than it is, and our colleagues who want to do this should be more professionally supported and valued than they often are.

Lesson #2 “No one owes you their eyeballs.”

People aren’t dumb and uncaring, but many are busy with many demands on their time and energy. You have to convince people that you and your message are worth listening to before they will listen, and that means getting people’s attention. It doesn’t matter how important you (or the entire expert community that you are a part of) believe the information to be if you can’t first convince people to stop what they’re doing and listen. This need not be an individual-level task, though, your whole community can band together to agree on strategies and talking points, but it needs to be done.

Some disciplines have inherent advantages in this fight for eyeballs, but working on an animal like sharks is more of a mixed bag when speaking to the public than some might realize. Sure, everyone knows what a shark is—some of my colleagues have to start their public talks with “this is what a seagrass is since you probably haven’t heard of it,” which I don’t have to do with sharks. However, there are different challenges with a well-known study system, because many people believe that they already know all of this… when in reality much of what they know is extremely wrong. I have to get people to still pay attention and keep caring while correcting harmful misinformation that contributed to them caring in the first place!

A related lesson is that people can walk away at any time for any reason—once you have peoples’ attention, don’t lose it by being boring, or condescending, or bigoted, or doomer (i.e., “this is hopeless and there’s nothing we can do to stop it so why try?”)

Lesson #3: Storytelling is more effective than a list of dry facts…and while facts will always matter, an infodump cannot be the sole focus of your public engagement.

Please note that when I say “tell a story” I don’t mean “make up lies,” but weave your key points (including but not limited to facts) into a format that is interesting to listen to.

A related lesson about sharing facts in your public science engagement concerns the “knowledge deficit model” of science communication. If you haven’t heard of this, you’ve almost certainly seen it in action. For example, if you think “I am an expert because I know all these facts, and I support policy outcome A, you are not an expert, you don’t know these facts, and you support policy outcome B. If only you knew all the facts I know, then we’d have the same policy preferences, so therefore I will vomit a bunch of facts at you.”

This doesn’t work, because people are more complicated and more interesting than that! The deficit model has been pretty widely debunked for a long time, which makes it all the more frustrating to still see it in use by far too many scientists trying to engage with the public.

That said, sharing accurate facts matters! Someone probably won’t change what policy preferences they support in response to an infodump of boring facts, but there’s no chance that they’ll change their policy preferences if they never learn the truth of what’s actually going on. As a specific example, just explaining to people that some fishing practices cause environmental harms probably won’t by itself cause someone to choose more sustainable seafood options for dinner, but they almost certainly won’t ever choose those options if they never learn about harms caused by their current choice in the first place.

Lesson #4 Saying that your research is important (for conservation, or otherwise) does not make it so.

I’ve often remarked that “it’s great that so many members of the public want to help sharks, and it’s great that so many members of the public are trying to help sharks, but wanting to help and trying to help are not the same thing as actually helping.” Whether or not a given conservation action actually helps is an answerable, measurable question!

The same is true of scientific research—we know what kind of research and data might be potentially helpful to endangered species management and what kind cannot possibly be helpful, because endangered species managers and conservation advocates have repeatedly told us. Unfortunately, far too many scientists, either because they want to feel like they’re helping or because they honestly don’t know what helping means, claim that their work is more important than it is. This is so big of a problem that the phrase “this research is important to the conservation and management of threatened sharks” has become a running joke in some corners of my field.

Not all science needs to be relevant to conservation, but don’t say that it is if it isn’t! And if you don’t know if it is, it probably isn’t! Other than risking a loss of public trust, you are contributing to public misunderstanding about conservation threats and solutions.

Lesson #5 Not every individual unit of science needs to be communicated to the public

It matters that our communities understand the role and value of science and evidence and expertise, and that they know how to recognize harmful pseudoscience. It matters that our communities understand key facts underlying some of the most important issues our society faces, and the best available evidence about the consequences of inaction or the wrong action.

But this does not mean that every result from every one of your papers needs a press release, or a social media campaign, or public speaking tour. When I give my public talks, I mostly highlight syntheses of results from many papers by many people, rather than all individual results from my papers.

It’s important to realize that your latest paper can be well done science that’s relevant to your subfield, but not matter that much to the lives of non-scientists in your community (or to the conservation of the species you’re studying). Your goal should be to help our community understand the role and value of science and evidence and expertise. If your goal is instead for your neighbors to think that you’re cool and important, it is possible to succeed, but success will matter a lot less!

Lesson #6 Unilateral disarmament doesn’t win battles, but you do not have to participate in every fight you are invited to.

Harmful misinformation should not stand unchallenged in the public square. Science, endangered species, and institutions of higher learning are under attack, and surrender is no way to win a fight.

In my world of shark conservation science, members of my professional society have an affirmative duty to speak up against harmful pseudoscience or misrepresentation of facts related to our field. (I wrote that part of our professional code of ethics). Again, facts aren’t the only thing that matter, but if people are exclusively exposed to incorrect facts created by extremists with harmful agendas, they will have an incorrect understanding of the problem and its possible solutions.

Importantly, this doesn’t mean that we need to waste hours every week arguing with all the trolls we find about whether or not the sky is blue. This is a lesson that took me far too long to learn. I used to spend hours engaging in very stupid arguments, and the next day I wouldn’t even remember what the argument was about. I’d just know that I was frustrated, and that I was several hours behind on work…and others would know it’s really easy to get me derailed and frustrated.

What I personally try to do now is respond once, sharing that something is wrong, how we know it’s wrong, what the right answer is, and how we know that. If the original troll wants to keep arguing nonsense, I won’t engage and may even block them.

My goal is not to convince the original troll or anyone who already believes their conspiracy theory nonsense, but to make sure that anyone earnestly trying to learn about the issue is exposed to reality. Any time you can stop someone from sharing nonsense, you help control its spread just a little bit.

Lesson #7: Know (and use) the right tool for the job, but tools by themselves are not a strategy. You need a strategy.

After one of my “how to use social media for public science engagement” workshops in Brazil, someone came up to me and said they were so excited to go home to Belize and practice using twitter for science education. However, their target audience, a community of Belizean shark fishermen, doesn’t use twitter at all, and they wondered how they could craft tweets to get their target audience’s attention. My answer was simple: you can’t. You have to go where your audience is.

Though recent Twitter nonsense has weakened them, social media and blogs are some of the most powerful tools ever created to amplify the messages of experts. These tools make it easier than ever before in human history for experts to share their knowledge with society en masse, and, accordingly, easier than ever before in human history for one person to make a difference. But any tool only works if you use it correctly. Just as a hammer isn’t useful for the same tasks as a chainsaw, different online communications tools have different strengths and different tasks that they’re better suited for.

Some social media platforms are widely used by journalists. Some are widely used by Gen Z Kids These Days (TM). Some are hyperlocal and specific to particular communities. Some are great for sharing videos and imagery, while others are great for sharing links with brief commentary. You should know which tool is right for the job at hand, and you should use the right tool for the job.

Relatedly, these tools are incredibly powerful ways to help achieve your goals as part of an overall communications and engagement strategy, but tools are not a strategy. In other words, “I’m going to tweet a lot” is an action in support of a strategy, but is not a communication strategy itself! Such strategies are usually built at an institutional, not individual, level, but they still form a useful framework for thinking about a data-driven strategy for engagement at any level.

I help to build communications strategies for non-profits or large collaborative research projects, and a brief description of some of the things we consider may help to illustrate this point. You should assess the current state of affairs, as well as what you would like to be different as a result of your intervention (i.e., what’s bad now and what do you want it to be like instead?) Without a measurable goal, you won’t be able to measure if you achieved your goal! You should also clearly identify your audience, propose several channels for disseminating information, and craft sample messages for different information channels and audience segments. I also stress the difference between an output (e.g., “I tweeted 20 times about the environmental harms of plastic shopping bags) vs. outcomes (e.g., “five social media followers purchased reusable canvas shopping bags because of my tweets.”) Outcomes are much harder to measure, but also matter a lot more!

If you’ve never before thought about adding measurable data-driven goals to your communications strategy, you’re not alone…but you’re also not especially likely to succeed.

Lesson #8: Treat your audience with respect. That includes how you carry yourself, how you respond to questions, and your word choice re: jargon.

No one has ever changed their mind because they were yelled at and insulted by a stranger, on the internet or in real life. Read that again.

Treating your audience with respect, which includes listening to them rather than talking at them, is vital for any sort of persuasion. It doesn’t guarantee success, but ignoring it comes close to ensuring failure.

I’ve had commercial fishermen talk to me and say “I’ve been doing this for decades, I’ve talked with many scientists and environmentalists, and you’re the first person who hasn’t acted like you think I’m stupid.” I tell them that I don’t think they’re stupid, I think they’re smart at something different from what I’m smart at—but I do think that they’re wrong about the particular issue we’re discussing that day.

This approach of treating people with respect even when you disagree with them strongly is challenging in today’s increasingly polarized-about-everything era, but you’re extremely unlikely to change someone’s mind if they think you hate them or think they’re stupid.

Even when you sincerely don’t think that someone is stupid, your word choices can make them feel stupid. I’m talking of course about jargon, highly technical language used exclusively within your hyper-specific subdiscipline. Jargon has its place, but that place is not public science engagement. Many scientists are taught (usually implicitly, sometimes quite explicitly) that the more 15 syllable words you can fit into a sentence, the smarter you are…but if your audience doesn’t understand what the heck you’re talking about, you weren’t smart enough to achieve your communications goals.

Lesson #9: Sometimes the messenger matters as much as the message… or more!

Sometimes achieving the broader societal goals of your communications strategy requires a little humility and a little sharing of credit and opportunity. It doesn’t matter how good of a communicator you are, there are communities that won’t listen to you or anything you have to say, but may listen to someone else who says the exact same thing. This may be because of demographics, or politics, or whether you’re known to disagree with them on an unrelated issue. Sometimes you need to work with a trusted messenger who is already accepted by the community you’re trying to reach and have them deliver the message.

Lesson #10: Professional need not mean stuffy dry and boring. This stuff should be fun!

Scientists have increasingly long to-do lists. If you see public science engagement as just one more thing you have to do, it becomes something you dread. Instead, you can do something fun, that you enjoy and look forward to! What that looks like is going to very enormously by person, but find what gets you excited and work towards that! If you love getting to dress up as your study animal and have a bunch of kids excitedly shout questions at you, do that! If the thought of doing that gives you anxiety, maybe write a blog post or op-ed, or share photos of your study site on Instagram.

Conclusions

It’s never been more important for scientists to break out of the ivory tower and engage with our communities- the stakes are too high for us to sit out of the fight! However, it matters what we communicate, how we communicate it, who we communicate to, and who does the actual communication. There are lots of ways of doing public science engagement, and no one right way to do it, but there are some tips that will increase your likelihood of success, and some common pitfalls to avoid. And you are much more likely to accomplish your goals if you develop a detailed strategic plan for how to use public science engagement to change your little corner of the world.