Joshua Moyer is an ichthyologist specializing in the evolution, biodiversity, and morphology of sharks and their relatives, collectively known as elasmobranchs. He is a member of the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists (ASIH) and the American Elasmobranch Society (AES). He has co-authored multiple scientific articles about shark teeth and their roles in understanding elasmobranch evolution. Joshua earned his Masters of Science in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Cornell University and teaches evolutionary biology at Ithaca College. Joshua also routinely lectures in courses on marine biology, vertebrate biology, and elasmobranchs. He has co-taught courses in shark biology in the field, laboratory, classroom, and most recently the online edX.org course “Sharks! Global Biodiversity, Biology, and Conservation.”

Joshua Moyer is an ichthyologist specializing in the evolution, biodiversity, and morphology of sharks and their relatives, collectively known as elasmobranchs. He is a member of the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists (ASIH) and the American Elasmobranch Society (AES). He has co-authored multiple scientific articles about shark teeth and their roles in understanding elasmobranch evolution. Joshua earned his Masters of Science in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at Cornell University and teaches evolutionary biology at Ithaca College. Joshua also routinely lectures in courses on marine biology, vertebrate biology, and elasmobranchs. He has co-taught courses in shark biology in the field, laboratory, classroom, and most recently the online edX.org course “Sharks! Global Biodiversity, Biology, and Conservation.”

Whenever I tell someone that I study sharks I can see their imagination shift into high gear. Their eyebrows go up, their mouths make an intrigued smile, and I’m usually asked whether I’ve gone swimming with sharks or if I’ve ever been bitten by one. Yes, I’ve been in the water with sharks. No, a shark has never bitten me (although I did drop the jaw of a Mako shark on my arm once – that left an interesting scar). I’ve also gone on shark tagging trips and many spent days as an undergraduate documenting the social behaviors of sharks in aquaria. Those are what I call my “dinner party stories.” They’re the anecdotes people expect to hear from a shark biologist. I’m frequently happy to oblige. However, I’d be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge that oceanic adventures are not essential to being a shark biologist, and they’re no substitute for curiosity and educated observation. In other words, you may see a shark, but you need to know how to really look at it – how to study it.

How do you learn to look at a shark or any other fish? Consider Samuel Scudder’s 1874 essay “In the Laboratory With Agassiz” (later re-titled “Look at Your Fish”). In it Scudder describes training under famed biologist Louis Agassiz. Shortly after meeting Scudder, Agassiz put a preserved fish in front of him and left Scudder to study it. Scudder grew tired, but Agassiz encouraged him to continue looking at the fish for days, periodically asking Scudder, “Do you see it?” Agassiz never actually told Scudder what “it” was, but Scudder did eventually remark that he realized how little he saw before. Scudder continued to cultivate his observational skills and did so without ever getting wet! As a result, he could ask new questions and observe new aspects of that fish’s biology

Almost 150 years since the publication of Scudder’s essay, careful observation in biological study is more important than ever! With new technologies, we have fresh ways of looking at just about anything you can think of. Consider the use of high-resolution computed tomography (CT). By using an ordered series of x-rays taken as a specimen is rotated between an x-ray emitter and a detector, scientists can reconstruct and dissect virtual two or three-dimensional specimen models. Enamored with this technology and intrigued by a large but often overlooked species of shark, the Gulper Shark (Centrophorus granulosus), I, along with my friend and former graduate advisor Willy Bemis, began to look at the teeth of Gulper Sharks in ways that Scudder could only have dreamt of.

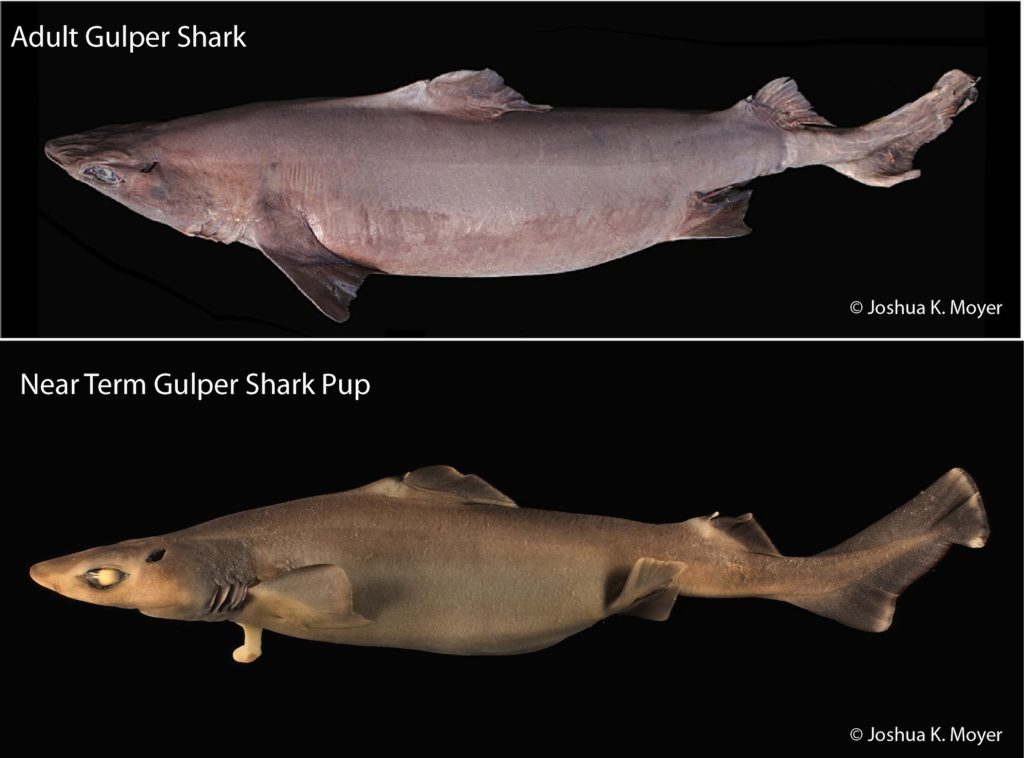

The Gulper Shark (Centrophorus granulosus) was originally named Squalus granulosus by Bloch and Schneider in 1801 and has since undergone multiple taxonomic revisions. Figure 1 shows a Gulper Shark adult and a pup. This shark is a large deep-sea relative of the Spiny Dogfish (Squalus acanthias) and lives close to the sea floor along continental shelves around the world. In the Western North Atlantic, the National Marine Fisheries Service occasionally catches Gulper Sharks as part of bottom trawl surveys. When this happens, biologists eager to study these sharks can put survey specimens to good use.

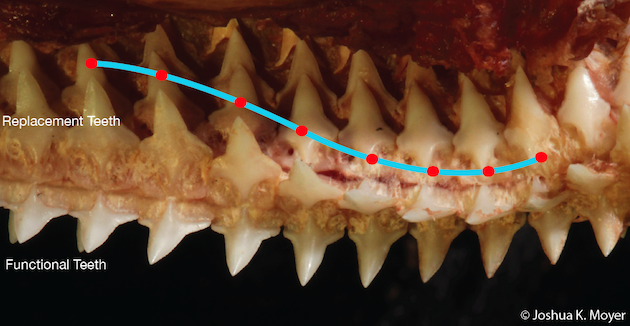

Teeth of Gulper Sharks, like those of many sharks, differ in size and shape between the upper and lower jaws (Fig. 2). In other words, Gulper Sharks exhibit dignathic (di = two, gnathic = jaws) heterodonty (hetero = different, donty = teeth). Upper jaw teeth are tiny and triangular. Lower jaw teeth are irregularly shaped, asymmetrical, and only slightly larger – about the size of the average pinky fingernail. In both jaws, the functional teeth visible from the outside, or labial side, of the jaw are backed by developing replacement teeth on the inside, or lingual side of the jaw. This is a tooth file. When a functional tooth of a tooth file is lost, the first replacement tooth moves labially into a functional position. In the lower jaw of the Gulper Shark, entire rows formed by the teeth of neighboring tooth files may be shed at once. However, as I learned, this is not the case in the upper jaw.

After several days of CT scan analysis and several more days photographing and illustrating the dentition of an adult Gulper Shark tooth by tooth, I noticed a strange pattern of tooth replacement in the upper jaw. Intrigued, I pulled out four more Gulpers from the lab freezer. Each had the same upper jaw tooth replacement pattern. When I showed Willy, he suggested sectioning the head of a Gulper Shark down the midline for a different view. I stood at a cautious distance as chunks of tissue flew while Willy guided a Gulper Shark head through a band saw. In the shower that night, as I was washing bits of shark out of my hair, I concluded that every comparative anatomist should have a band saw because sometimes all you need is a new point of view to see something fascinating.

When we peered from inside the mouth at the upper jaw, we saw a wave-like pattern of replacement teeth. The replacement teeth were moving into functional positions not as entire rows or even individually, but in a phased pattern. The effect was that of a sine wave (Fig. 3). Imagine a crowd in a sports stadium that gets up to do “the wave.” In this scenario, as the wave passes, instead of standing up then sitting down, the person closest to the field jumps out of the stands, and the person behind them moves up to take their seat. That is essentially the tooth replacement pattern we saw emanating from the center of the upper jaw in the Gulper Shark – a tooth replacement wave on the left and right halves of the jaw that we called a phased sinusoidal replacement pattern.

Our observation of a phased sinusoidal tooth replacement pattern in Gulper Sharks was eventually published in the July 2016 issue of Copeia, the journal of the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, along with some observations of tooth histology. Seeing one’s research published in a peer reviewed journal means different things to different people. To some it’s a piece of currency in the academic realm. For others it’s a bit of immortality. For me it’s confirmation that I’ve contributed to a body of knowledge I’m passionate about, and hopefully we’ve provided our successors with information they can use to solve their own puzzles. Our Gulper Shark study, I have come to see, is truly an artifact of the spirit of enthusiasm, curiosity, and attention to detail that drove so many before us to look at their fish. Regardless of what fish life has put before you, when you think you’ve observed everything there is to see, flip that fish over and start looking at the other side. If you are patient enough, then there is always something else to see.