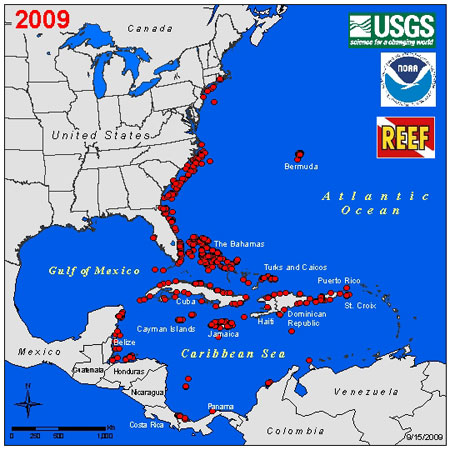

Last time you went to an aquarium, you probably saw a lionfish swimming happily in a tank filled with a bit of coral or rocky bottom, calmly flipping its fins about in the slight current created by the water pump. Now think back to the interpretive sign next to the tank – did it say that the exhibit displayed an invader or an awesome, weird aquarium fish? Depending on which part of the world you’re in, you might get a different answer. Along the east coast of the United States, though, it should say the former. Lionfish have spread from south Florida throughout the Caribbean and up to North Carolina, where they can be found on reef habitat (either natural or manmade via the sinking of ships) at a concentration of 400 fish per square meter. And they eat everything in sight.

Last time you went to an aquarium, you probably saw a lionfish swimming happily in a tank filled with a bit of coral or rocky bottom, calmly flipping its fins about in the slight current created by the water pump. Now think back to the interpretive sign next to the tank – did it say that the exhibit displayed an invader or an awesome, weird aquarium fish? Depending on which part of the world you’re in, you might get a different answer. Along the east coast of the United States, though, it should say the former. Lionfish have spread from south Florida throughout the Caribbean and up to North Carolina, where they can be found on reef habitat (either natural or manmade via the sinking of ships) at a concentration of 400 fish per square meter. And they eat everything in sight.

It’s easy to think they’re pretty, cute, or would otherwise make a nice addition to a fish tank in your living room. However, that’s how these invaders first found their way into Floridian waters – someone decided they didn’t want theirs anymore and dumped their fish into the network of the Florida Everglades. Well, actually, it was at least two, and most likely 4 separate introductions of lionfish that decided they liked the warm Floridean waters and decided to call them home and find a mate. Which they did.

Lionfish originally hail from the Indo-Pacific, mainly around Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand. There, as they do in their new habitats, they literally vacuum up small fish by herding their prey using their long fins so they can scoop up large numbers of prey at once. Lionfish aren’t picky eaters, either, and are known to clear out an area of their prey in a matter of hours. But that’s only one side of the equation – nothing in the Atlantic can eat lionfish, which are protected by the venom at the tip of each spine arising from its back. These spines make lionfish difficult to catch for either bigger fish or for human fishers. But that doesn’t mean it can’t be done, and these efforts might be the only hope for warm Atlantic water ecosystems under invasion.

Lionfish originally hail from the Indo-Pacific, mainly around Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand. There, as they do in their new habitats, they literally vacuum up small fish by herding their prey using their long fins so they can scoop up large numbers of prey at once. Lionfish aren’t picky eaters, either, and are known to clear out an area of their prey in a matter of hours. But that’s only one side of the equation – nothing in the Atlantic can eat lionfish, which are protected by the venom at the tip of each spine arising from its back. These spines make lionfish difficult to catch for either bigger fish or for human fishers. But that doesn’t mean it can’t be done, and these efforts might be the only hope for warm Atlantic water ecosystems under invasion.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JGNGAlXZnKY

Researchers are teaching grouper to eat lionfish that are invading their territory off the Carolinas. They aren’t affected by the poisons, but don’t recognize the lionfish as food since they aren’t familiar with the new potential prey item. Grouper, however, are apparently smart enough to be taught that lionfish are in fact food. And for that matter, so are humans. A partnership between NOAA and REEF is encouraging divers to capture their dinner and will teach you how to fillet your lionfish and make it taste delicious. Suggested recipes include ceviche, lionfish ribs, and fried lionfish bites. According to some population modeling by James Morris and James Rice, if people decide that lionfish constitute a tasty dinner, the pace of the invasion could be slowed or stopped, with humans acting as primary predator for the lionfish. So get cooking!

References:

James Morris, NOAA Center for Fisheries Research at Science Cafe in Atlantic Beach 7/12/10.

http://animals.nationalgeographic.com/animals/fish/lionfish/