Though the fisheries news cycle has mostly been taken up by the 15-year anniversary of the Sea Around Us project (and some choice words between researchers), today also marked the official announcement of the 12-month finding on the petition to list dusky sharks on the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Long story short, the National Marine Fisheries Service has decided that the dusky shark population in the Northwest Atlantic doesn’t need ESA protection to avoid extinction. While it may be tempting to decry NMFS’ decision as falling short for a species that has long been a prime example of declining shark populations, what it actually means is that things are looking up for the dusky shark. Finding that out only takes a little reading into the decision documents.

Dusky sharks (Carcharhinus obscurus) are the archetypal requiem shark, with a rounded nose, dark grey coloration, large teeth, and a curved dorsal fin. Basically, if you asked someone to draw a shark (and they didn’t draw a great white or hammerhead), they would probably draw something that looks like a dusky shark. Dusky sharks also have all the characteristics of a species that shouldn’t handle fishing pressure well, growing slowly, maturing late, and producing few offspring. Sure enough, dusky shark populations crashed with increased U.S. fishing effort in the 70s and 80s, and the Northwest Atlantic population was estimated to be down to about a quarter of its original numbers by the mid-90s.

The flipside of being highly vulnerable to fishing mortality is that natural mortality is very low for this species. Being born nearly three feet long and attaining larger sizes than any other shark in the Carcharhinus genus means there are few marine species that can take down a dusky shark at any life stage. With that in mind, a rebuilding plan for the dusky shark should be conceptually pretty easy: reduce the sources of mortality that we humans are responsible for (especially on juveniles) and the sharks should be able to take care of themselves from there. So in 2000 NMFS included dusky sharks in the list of prohibited species and created a time/area closure off of North Carolina designed to protect juveniles.

Unfortunately, rebuilding the population of a long-lived, slow-growing species takes time, and dusky shark populations were projected to take over 100 years to recover. It didn’t help that dusky shark populations remained stubbornly low while other species such as sandbar sharks and spiny dogfish began to increase back to healthier levels. Both shark fishermen and conservationists grew impatient. While commercial and recreational shark fishermen chafed under restrictions placed on Atlantic shark fisheries, in 2012 WildEarth Guardians petitioned NMFS to list the dusky shark as endangered or threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA), and the National Resources Defense Council followed up with their own petition in 2013, which also asked for designation of critical habitat.

When a marine species is petitioned for ESA listing, NMFS is required to conduct a 90-day finding, followed by 12-month assessment to determine whether that species is at risk of going extinct without ESA-level intervention. Listing as Endangered represents the nuclear option for species conservation under U.S. law, and is not a decision to be made lightly. Basically, if current protections or policies look like they’re doing the job of keeping a species from going extinct, then listing on the ESA shouldn’t be needed.

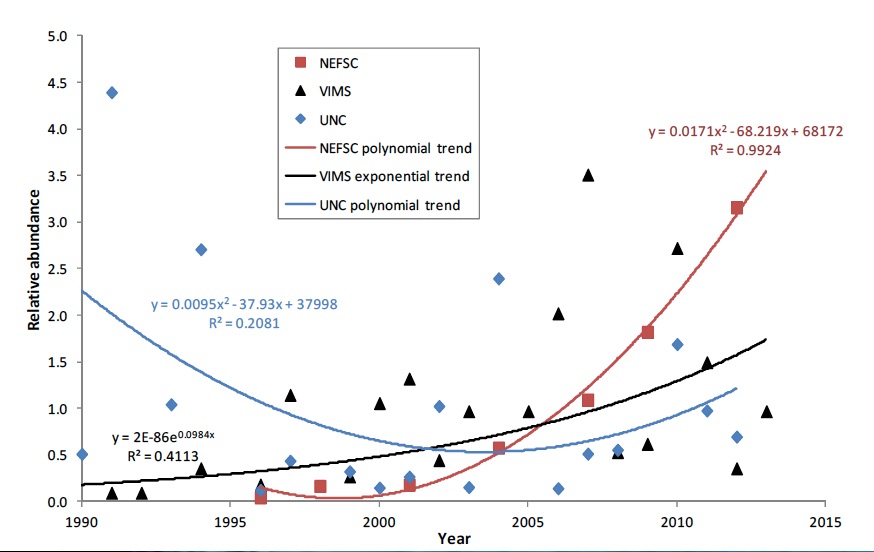

When NMFS researchers conducted the 12-month assessment to determine whether or not dusky sharks needed ESA protection, they found something interesting: the policies put in place to rebuild dusky shark populations had started working. By looking at several different data sources, including fishery landings and fishery-independent shark surveys, the assessment team found that in the late 2000s abundance indices for dusky sharks began to rise. This followed a period from the early 90s through 2005 during which dusky sharks populations had remained at a low, flat level. What the team found was that already-existing dusky shark management measures, combined with other management policies put in place on Atlantic shark fisheries, effectively shifted fishing effort away from dusky sharks and habitat areas important to them. Though it took longer than expected (again, this is a very long-lived and slow-growing species), these measures had reduced fishing mortality on dusky sharks long enough to allow older juveniles to survive to reproduced, and encourage survival of younger juveniles. After nearly a decade and a half, there is finally good news for the dusky shark.

The finding that ESA listing for dusky sharks isn’t warranted is a sign that current policies are working. These are the first signs of recovery for the dusky shark, and should be celebrated as such. While dusky shark numbers are still far below what they should be to sustain a fishery, at least this is proof that more restrictive measures are not currently needed. Aside from this brush with the Endangered Species Act, NMFS is currently reviewing Amendment 5b to the Highly Migratory Species management plan, which is is specifically concerned with encouraging and speeding up dusky shark recovery. With any luck, managers will be able to keep up the good work and the dusky shark can reclaim its spot as one of the most common sharks on the Atlantic coast.