NOAA, the US government science and management agency in charge of sustainable fisheries, the national weather service, and ocean exploration, is in the crosshairs of the Trump administration and Project 2025. Though criticisms from “small government” types imply that having a US government science agency at all represents some kind of expansion of government power beyond what the Founding Fathers intended, it’s perhaps worth noting that NOAA, formally created in in 1970, is the descendant of an ocean science agency that was created during the Presidency of Thomas Jefferson.

The logo for the US Coast and Geodetic Survey, which was founded in 1807,

and later became part of NOAA.

NOAA’s wasn’t created out of thin air, it’s establishment in 1970 combined several pre-existing scientific agencies, putting them under one roof. As noted by the NOAA Heritage program, “Although NOAA was formed in 1970, the agencies that came together at that time are among the oldest in the Federal Government. The Survey of the Coast [renamed the Coast and Geodetic Survey in 1878] was formed in 1807, the Weather Bureau formed in 1970, and the U.S. Commission on Fish and Fisheries formed in 1871. Much of America’s scientific heritage resides in these agencies.”

The Coast and Geodetic survey, formed in 1807, was the first scientific agency created by the United States government, and for decades was the only scientific agency in the country. So why was it created, and what did they do?

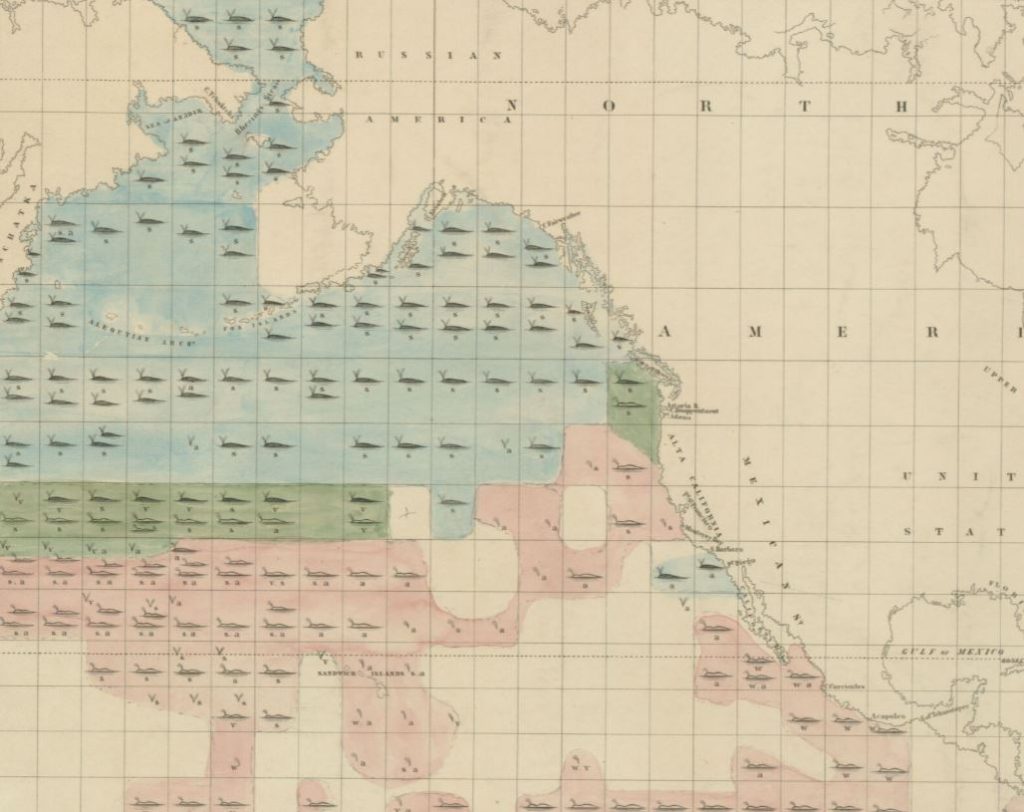

“People recognized the need for ocean science for defense and economic reasons, and sold it to Congress in those terms,” Penelope Hardy, an Associate Professor of History at University of Wisconsin La Crosse told me. “This included tracking whales to benefit New England whalers, and tracking currents for merchant clipper ships. The US Navy needed calibrated instruments and detailed charts, though they compained that we had to order charts from Europe and said we needed to create our own to establish complete independence. And as the country kept growing, there was more charting to do.”

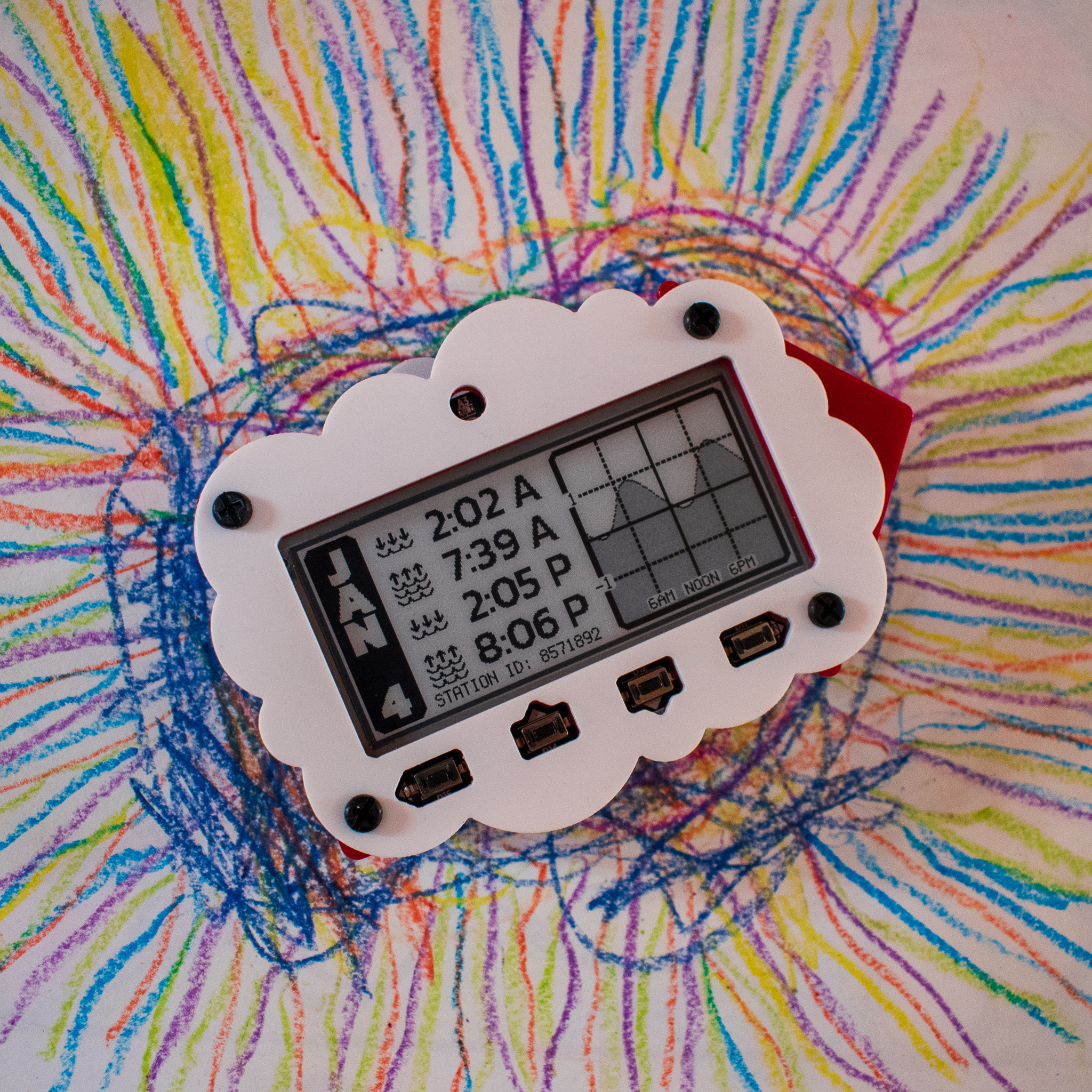

One of the economically and scientifically important documents produced by Matthew Fontaine Maury’s team was the “Whale Chart,” a map of where different species of whales were most likely to be found.

“From the beginning of the United States, it seemed kind of obvious that if American commerce was to be strong, it had to be safe,” Helen Rozwadowski, a Professor of History and Maritime Studies at the University of Connecticut, told me. “It wasn’t problematic or controversial or confusing to people at the time, there weren’t objections to making commerce safer by studying coasts and currents. The economic engine behind imperial power was maritime, and it’s in the interest of those powers to study the ocean. Funding and supporting this work was understood and very clearly connected to making our commerce safer and more profitable, and to American pride in our own science.”

This idea of patriotic pride in US science was critical to the expansion of the Survey under it’s second leader, Alexander Dallas Bache, who later became the first head of the National Academy of Sciences. “Bache wanted American science to be more professionalized and respected abroad,” Hardy told me. “Europe had looked at America as a colonial place to get resources, including specimens and scientific observations from, but those had been taken to be processed and analyzed by European scientists. Bache’s efforts helped put the US on the map in terms of international science, the data they collected was important at the time, and some of it remains important and used today.”

During this era, Joseph Henry, the first Secretary of the Smithsonian, started collecting basic meteorological data. “Henry set up a network of farmers throughout New York state to collect meteorological readings, and send them by mail and eventually by telegraph,” Hardy told me. “He also hired a network of data analysts to crunch the numbers.” This eventually became the National Weather Service, also now part of NOAA, and was reported on at the world’s first international meterological scientific conference.

Some research at this time was purely scientific in nature, without a clear military or commercial application. “Before this era, mariners asked ‘how shallow is the ocean,’ which matters from a safety perspective,” Rozwadowski told me. “This era marked the beginning of asking ‘how deep is the ocean, and what does it look like?’ Those questions were just pure intellectual curiousity, without a clear application of the information in mind. And Americans were proud that it was American technology that helped launch this era of deep sea exploration, and this played a role in the 19th century economic expansion of the United States.” Specimens collected during expeditions in this time became part of the Smithsonian’s internationally-renowned collection of fishes and marine life.

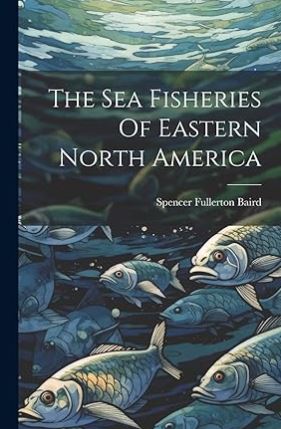

Near the end of the 19th century, Spencer Baird served simultaneously as the first commissioner of the US Fish Commission (which became NOAA’s National Marine Fisheries Service) and the second Secretary of the Smithsonian. In 1884, he wrote “Inquiry Into the Decrease of Food- Fishes in Waters of the USA,” which represents some of our earliest understanding of the threats posed by overfishing, as well as many other highly influential works in fisheries management. There’s now a research vessel named after him.

Nowadays, NOAA provides vital (and economically valuable) services to all Americans, and if it were to be lost or diminished it would be a great tragedy. But it’s important to note in these discussions that the concept of a US government funded agency to study, manage, and protect ocean resources is not in any way a new or radical idea. “Something like NOAA has existed for almost two centuries,” Hardy told me. “The name NOAA doesn’t go back that far, but it’s the clear continuation of efforts that have been going on for a long time.”

You can learn more about current attacks on NOAA, and how to support them, here.