Objective 1: Develop the least publicly accessible title for a blog post about seadragons, mate selection, and evolution

Objective 1: Develop the least publicly accessible title for a blog post about seadragons, mate selection, and evolution

Objective 1 Status: complete

Objective 2: Draw in whatever readers push passed the unwieldy title with an unconventional narrative structure.

Objective 2 Status: complete

Objective 3: Hook the reader with a fascinating, though brief, background on seahorses, seadragons, and pipefish.

The 230 species of seahorses, seadragons, and pipefish are arranged into 52 genera in family Syngnathidae. All species within Syngnathidae evolved male-pregnancy, however, there are two distinct flavors of Syngnathid sex. Pipefish and seadragons are tail-brooders (Urophori) – the females lays her eggs in a depression on the male’s tail and the males fertilizes the eggs and carries them until they hatch. Seahorses are abdominal brooders (Gastrophori) – the female delivers her eggs via a tube-like structure called an ovipositor into the male’s ovireceptor. The male then fertilizes the eggs in an internal pouch and carries them to term. This unusual trait makes Syngnathids ideal model organisms for study the evolution of sex and reproductive strategies.

Seahorses are in trouble. Prized in the aquarium trade and for traditional medicine, many Syngnathid species have been harvested to near extinction. Add to that habitat destruction (seahorses and pipefish thrive in seagrass beds, coral reefs, mangroves, and other threaten ecosystems) and the future looks grim. The last 10 years has seen a 20% population decline for most seahorses (when data is available). Two seadragons, 8 seahorses, and one pipefish are listed as either Near Threatened, Threatened, Endangered, or Critically Endangered by the IUCN (see full summary here). South African Syngnathids are in particular trouble. The Knysa seahorse, South Africa’s only resident seahorse, is the most endangered seahorse in the world, and the South African river pipefish is the only Syngnathid listed as Critically Endangered.

There is hope though. Tighter government regulations have made the export of seahorse difficult. Captive breeding programs have lessened the pressure on wild stocks. Most public and private aquaria and zoos only stock captive bred animals, and have strong public outreach conservation components to their displays.

Objective 3 Status: complete

Objective 4: Create a personal connection to the reader by reminiscing about my first lab experience as a high school student working at the National Aquarium in Baltimore.

My first job in marine science was at the National Aquarium in Baltimore. I spent my last two years of high school in the Syngnathid Breeding Program working with Jorge Gomezjurado. Jorge grew up in Ecuador and spent years working in the Galapagos Islands before moving to the Steinhart Aquarium in California and then the National Aquarium in Baltimore. In our very first meeting, before I was even hired, Jorge offered to take me out on a Chesapeake Bay collecting trip to find lined seahorses, Hippocampus erectus, common to the mid-Atlantic US. This was my very first chance to really participate in the process of marine science.

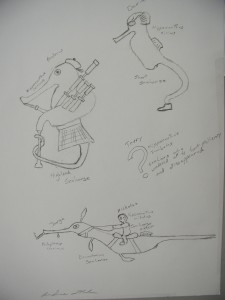

For the next two years I worked weekends and summers in the seahorse lab. Most of my job involved the literal ins-and-outs of fishes – feeding them and then cleaning up their poop. Most of our seahorses were breeding stock – Hippocampus kuda, H. breviceps, H. erectus, H. abdominalis – many destined for the National Aquarium’s seahorse exhibit. But our real goal was captive breeding some of the rarer creatures. We had both weedy and leafy seadragons, pygmy seahorses, several species of pipefish. We designed tanks, flow through systems, carefully controlled seawater mixtures, all for the purpose of decreasing seahorse mortality and increasing reproduction.

We had some success. Many species reached the point where they would produce offspring consistently over the months. These would be sent to other AZA certified aquariums, lessening the demand for wild-caught seahorses and exposing even more of the public to these weird and wonderful creatures. We even had several attempted (though unsuccessful) matings by seadragons – the holy grail of seahorse breeding.

But mostly what I did was learn to manage a lab. As I gained experience, Jorge trusted me with more responsibilities. I went from lowly high school volunteer to assistant aquarist. On weekends I would often be in charge of everything. Eventually, I was designing my own experiments and building my own tank systems, learning all the necessary skills along the way.

Beyond just learning the skills, I also learned how to manage people, a tool that would become essential on long research cruises. The task of training new interns and volunteers fell to me. For someone just beginning the long road towards a career in science, that kind of mentorship is more valuable than any class, field experience, or research grant.

Objective 4 Status: complete

Objective 5: Now that the reader has an intellectual investment in seahorses and an emotional investment in me, dig into the gory details of seahorse systematics

Seadragons are Syngnathids that possess leafy protrusions that allow them to camouflage with kelp, seagrass, and other marine plants. This camouflager is essential because seadragons tend to be very poor swimmers. Although often grouped together, seadragons are not monophyletic. Several different models of seadragon evolution have been proposed. The most recent phylogeny proposes that each seadragon is a distinct clade and that the camouflage protrusions have evolved separately and convergently multiple times in seadragon history. Wilson and Rouse recently attempted to resolve the phylogenetic relationships among seadragons.

Wilson and Rouse (2010) screen multiple mitochondrial markers to determine the optimal phylogeny for seadragons. Not surprisingly, but in contrast to previous studies, they showed that the weedy and leafy seadragons are closely related sister taxa, but the ribbon seadragon is not closely related. Thus camouflage appendages evolved at least twice, and that it may be more accurate to refer to the ribboned seadragon as a pipefish.

They also established that weedy and leafy seadragons emerged in the late Miocene, and estimate which is consistent with the earliest known kelp fossils, suggesting that these species evolved as the habitat that they rely on for protection emerged.

Digging deeper into Syngnathid phylogeny, they revealed that the sub-family Syngnathinae, which includes all pipefish and seadragons, is also not monophyletic, and that many previously ignored sub-families should be restored.

Finally, Wilson and Rouse throw a wrench into the seemingly neat division between Urophori and Gastrophori, reporting the abdominal brooding has emerged in groups that are more closely related to tail-brooders.

Objective 5 Status: complete

Objective 6: Wax philosophical about the role of mentors in developing young scientists.

Dedicated mentorship is critical to the future of all science. Without strong, committed mentors willing to take the time to nurture not just young scientists, but people who might become young scientists. Without Jorge Gomezjurado’s guidance, I doubt that I would have found my way into marine science. No one sums it up better than Neil deGrasse Tyson, describing his own first encounter with Carl Sagan:

“Who am I? I’m just some high school kid.”

Objective 6 Status: complete

Objective 7: Bring the reader back to the main point of this article, which is probably lost in a quagmire of self-indulgence, by concisely summarizing the finding of Wilson and Rouse (2010).

Seadragons are not a monophyletic group, although the charismatic weedy and leafy seadragons are sister taxa which emerged in conjunction with kelp forests in the late Miocene. Sub-family Syngnatinae is also not monophyletic and resolving its phylogeny may shed light on the evolution of male-brooding. Urophori and Gastrophori are not phylogentically supported groups.

Objective 7 Status: complete

Objective 8: Show a picture of Hippocampus kuda mid-coitus.

Objective 8 Status: complete

Objective 9: Profit!

Objective 9 Status: pending

Objective 10: Sign my work and give photo credit.

~Southern Fried Scientist

All images taken by Andrew Thaler, unless otherwise noted.

Objective 10 Status: Complete

Objective 11: Provide a citation for research articles.

Wilson, N., & Rouse, G. (2010). Convergent camouflage and the non-monophyly of ‘seadragons’ (Syngnathidae: Teleostei): suggestions for a revised taxonomy of syngnathids Zoologica Scripta DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-6409.2010.00449.x

Objective 11: complete

Obective 12: Link to article about Jorge Gomezjurado’s work

Objective 12: Complete

I love me some convergent evolution! It’s always simultaneously surprising, and completely unsurprising. A hard emotion to articulate.

Also love this post layout – I laughed very hard. Great job

–Hannah

Currently, the Leafy sea dragon and Lined seahorse are placed in different subfamilies, I recently looked at the bile salts of one of your Lined seahorses. In support of convergent evolution, it was so completely different from that of a Leafy seadragon as to strongly suggest that these two fish species should be in different families altogether.