This is the transcript of the keynote I delivered at the Fourth International Marine Conservation Congress in St. John’s, Newfoundland. It has been lightly modified for flow.

Good morning and thank you all for coming, especially this early after a long week of conferencing. What I want to do today is talk a little bit about the history of online outreach, talk about how to build effective outreach campaigns, and look towards the future to think about how new technologies are shaping and reshaping the ways in which we think about public engagement with science and conservation.

So science is storytelling. Sometimes that story an adventure. Sometimes it’s a mystery. Sometimes it’s the dense and weighty exposition of Ulysses and sometimes it’s the absurdity of Finnegan’s Wake, but it is always a story.

So science is storytelling. Sometimes that story an adventure. Sometimes it’s a mystery. Sometimes it’s the dense and weighty exposition of Ulysses and sometimes it’s the absurdity of Finnegan’s Wake, but it is always a story.

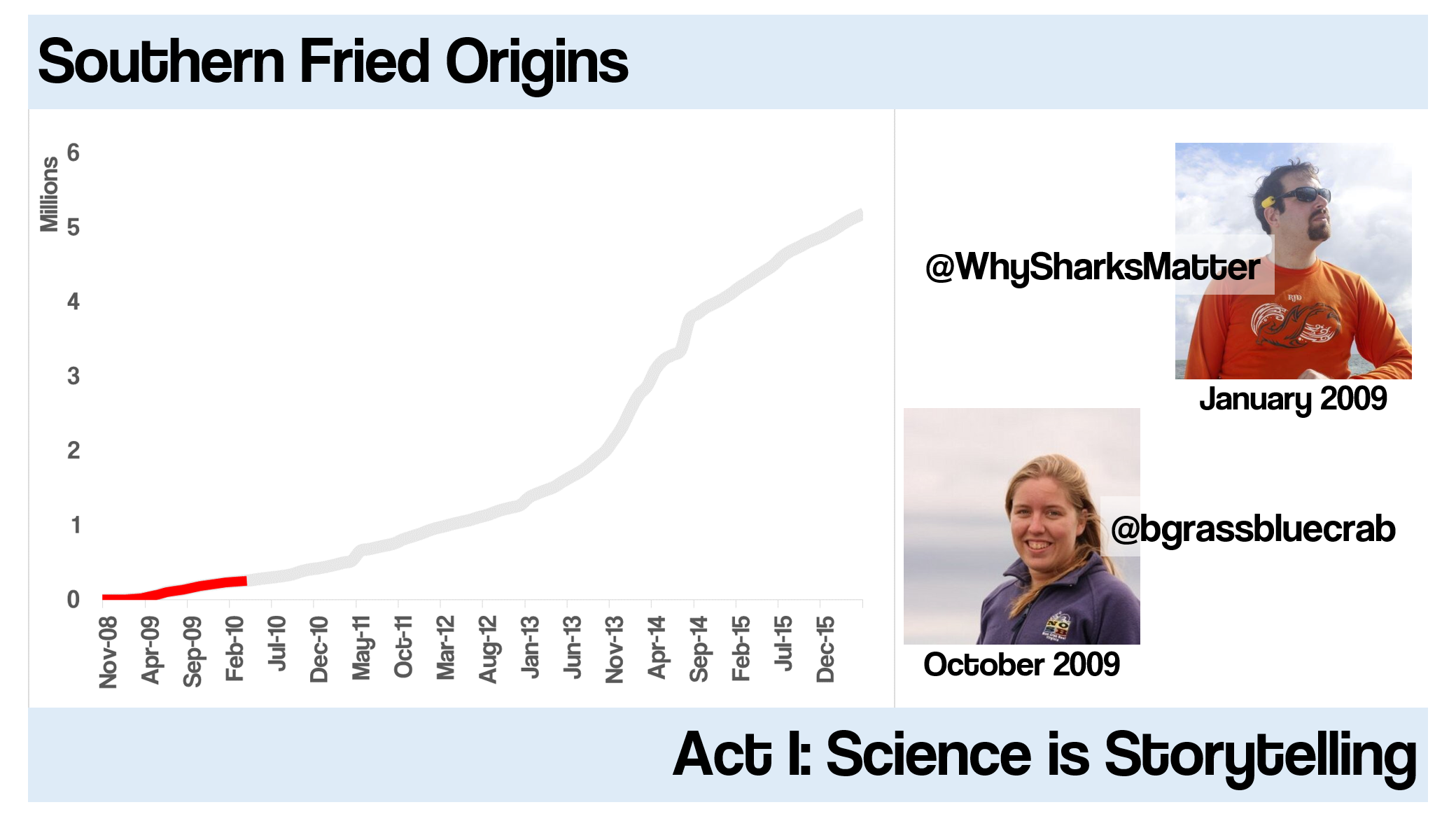

I’m going to start with the story that I know best and that is the story of my own website Southern Fried Science. I started this blog in November of 2008. It began as a writing lab, a place for me to practice my wordcraft and hone my skills as a popularizer of science. And it started with what, in retrospect, is a very naïve vision, but one that at the time I felt very strongly about: that we have a duty to not just report the science but to humanize the scientists, to let people know that there’s a person behind the research. At the time a lot was being written about how few scientists American citizens personally knew and how often science was seen as a faceless endeavor conducted by nameless white lab coats, invariably all male.

I launched the site during a time when the internet was swimming in small, independent science blogs, great blogs, some of which are still around, like Deep Sea News, but many of which have since vanished into the deep archives of the internet. Over the next year, I added two writers to the site, David Shiffman who has gone on to become a force of nature in the science communication world, and Amy Freitag who has carved out an impressive niche among mappers and social scientists.

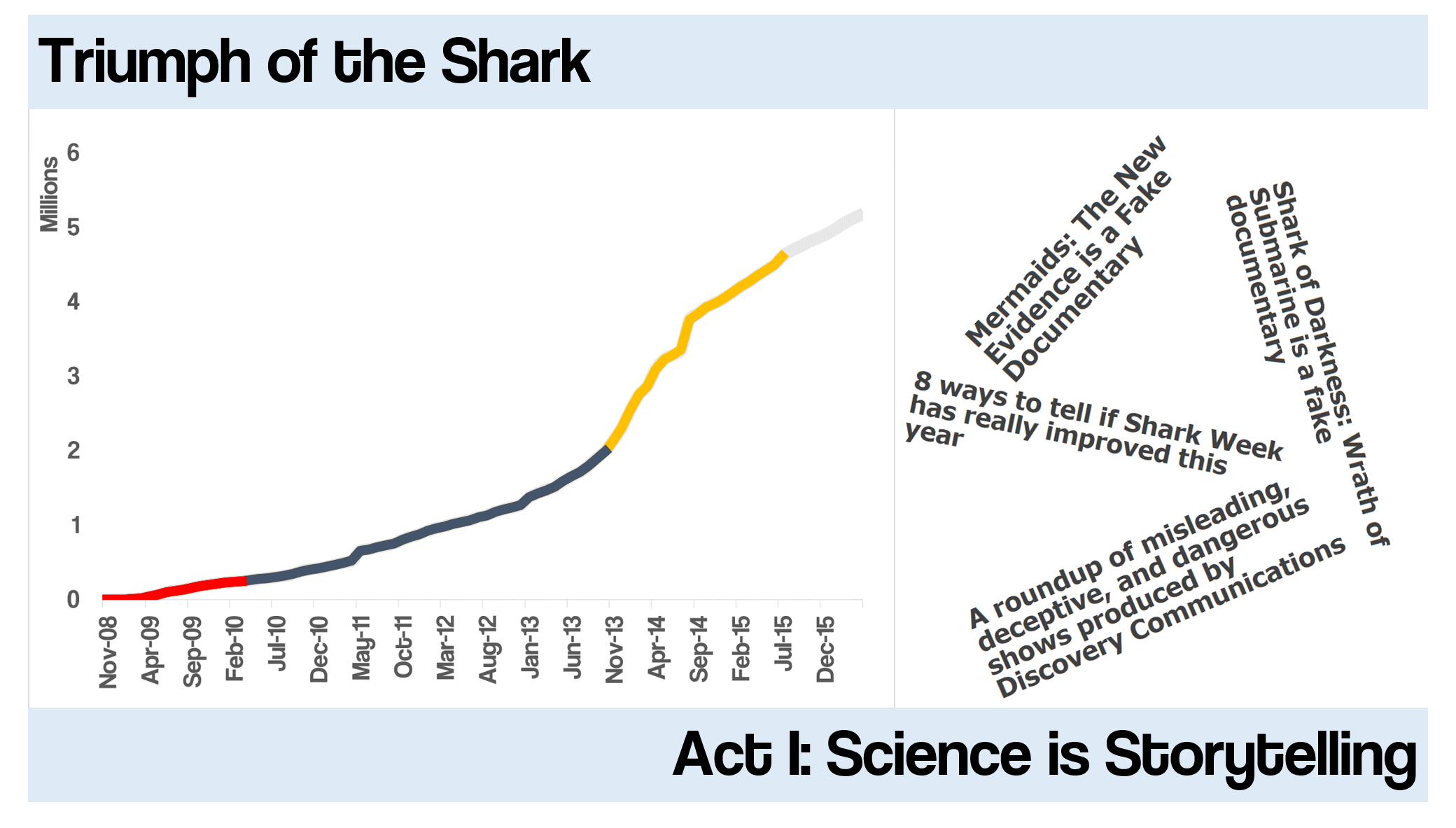

Our growth was slow, steady, and predictable. This graph, which you’re going to see a few more times, is the number of cumulative unique visitors, in millions, over the history of our website.

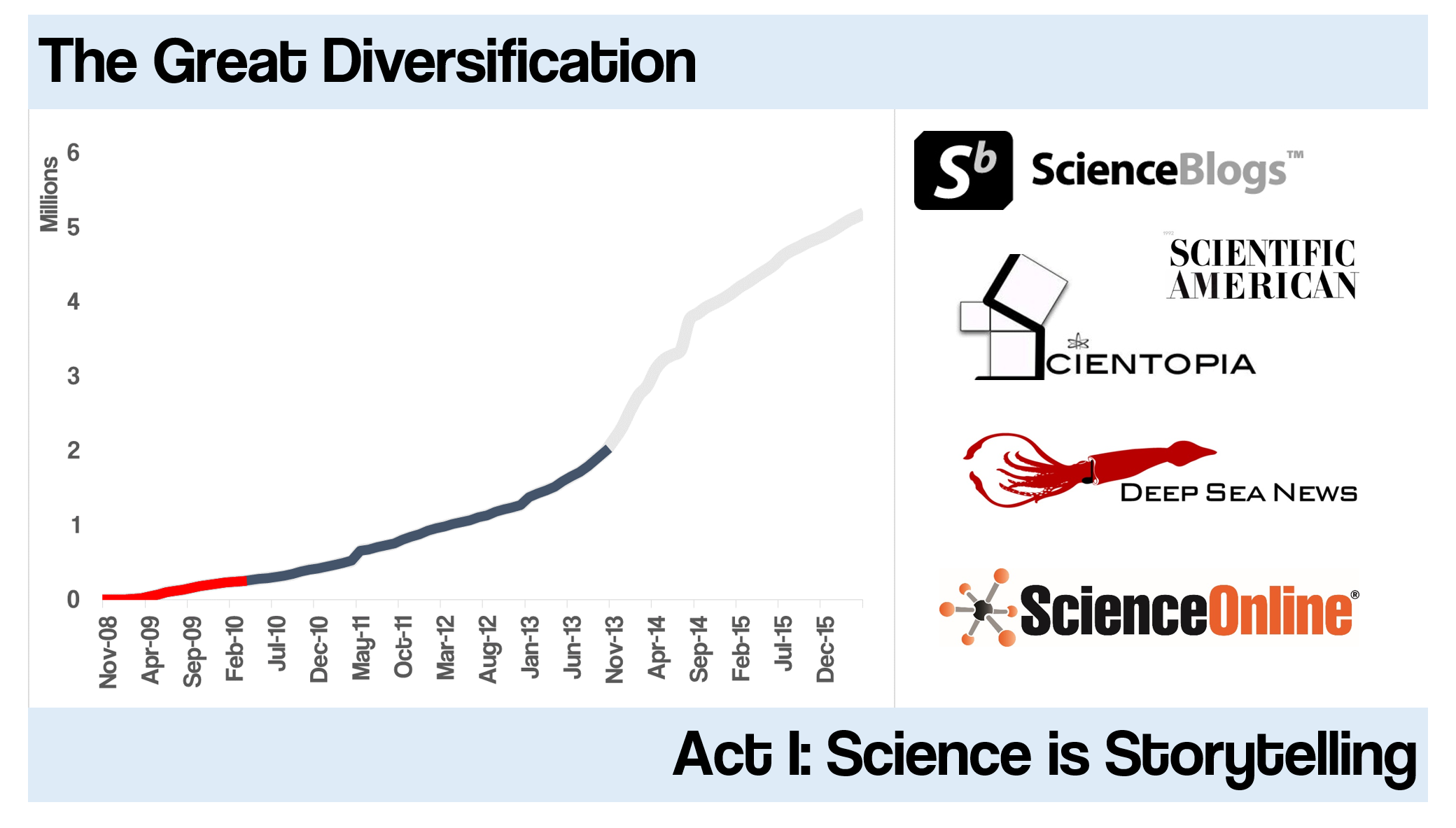

At some point in early 2010, science blogging underwent tectonic shifts in the structure and underlying organization of the community. This epoch, which I’m calling the Great Diversification, began with a blog called Food Frontiers. Food Frontiers was a food blog, but it wasn’t just any food blog. It was a blog at ScienceBlogs which was at the time the largest and most trafficked science blogging network in the world. And it wasn’t really a blog either. Food Frontiers didn’t join ScienceBlogs the way every other writer on the site joined, by creating great independent science content and then reaching out to Seed Media, who ran ScienceBlogs. Rather it was a blog created by PepsiCo, who paid Seed Media for the right to publish on the ScienceBlogs platform and was written by PepsiCo’s employees. It was an ad. Now I’m sure PepsiCo has great scientists and perhaps they could have written about food matters and nutrition in an unbiased scientific and thoroughly entertaining and engaging way, but the fact that this was paid content, what we’d call native advertising in 2016, that was completely unacknowledged and looked like every other blog on the ScienceBlog Network, did not sit well with many of their writers. This inspired a wholesale migration of great science writers away from ScienceBlogs platform. Some started new blogs. Some started entire new networks. Some went on to write for more traditional media sources and some simply didn’t return to science blogging. ScienceBlogs the network never really recovered and Seed Media sold it a few years later to National Geographic.

This was great for smaller independent blogs. ScienceBlog’s audience was huge and they were seeking out new blogs, looking for new sites and discovering these great independent blogs as well as brand new blogs emerging during this time.

This Great Diversification begins with the collapse of the biggest science blogging network,which ended up being a net positive for science blogging as a whole, but it ends with the self-destruction of ScienceOnline, one of the most important communities of science communicators. ScienceOnline hosted several annual conferences that brought formal and informal science communicators together. They brought bloggers and journalists and videographers and practicing scientists under one roof to talk about science and storytelling and communication. ScienceOnline was the inspiration for OceansOnline. Unfortunately, the institution of ScienceOnline couldn’t survive a sexual harassment scandal by its founder and chief architect and, in late 2013, the organization finding its reputation in tatters and attendance at its flagship meeting deeply depressed, shuttered its doors.

Incidentally, if you haven’t had a chance to read the IMCC Code of Conduct, you should. It’s truly exceptional and a model for how conferences can and should safeguard their attendees. The paper “Your science conference should have a code of conduct” that Sam and Chris and several others published in Frontiers in Marine Science is also really great.

Have y’all heard about Shark Week?

Shark Week is this thing that Discovery Communications puts on every summer. It’s a week of shark specific programming, some of which is good and some of which is really bad. Right around the time that ScienceOnline was falling apart Discovery began making some truly awful fake documentaries. Not the classic reality-show-is-often-scripted style programs but entirely fabricated documentaries with no warning and barely any disclaimer that they were fake. These were well-crafted programs. They were compelling. They were the kind of documentary you wish you could make if only you had unlimited access to your sources. If you could get the perfect quote. If you could always get the right shot. If you could make your documentary match whatever story you wanted to tell because, of course, they were making up the evidence and hiring actors and that was not great, but even worse, people were believing them and believing them in non-trivial ways.

We can joke about how Andrew and David were obsessed with mermaids and megalodons and yeah here’s a fake documentary and that’s bad but is it really that bad for society? I’ll leave you with one small anecdote that happened to me as I was talking to a 5th-grade school teacher on my flight home from IMCC3. She said this: “If NOAA is lying to us about the existence of mermaids then they’re definitely lying to us about climate change.”

So with 5 years of experience behind us doing science outreach online, creating engaging ocean science content, we essentially went to war with Discovery Communications. On our main site, we published numerous articles about these documentaries, using data-driven choices about how to frame these arguments to maximize their social reach as well as harnessing a vast network of engaged online activists through an NGO called Upwell, who were the undisputed masters of data-driven Big Listening campaigns.

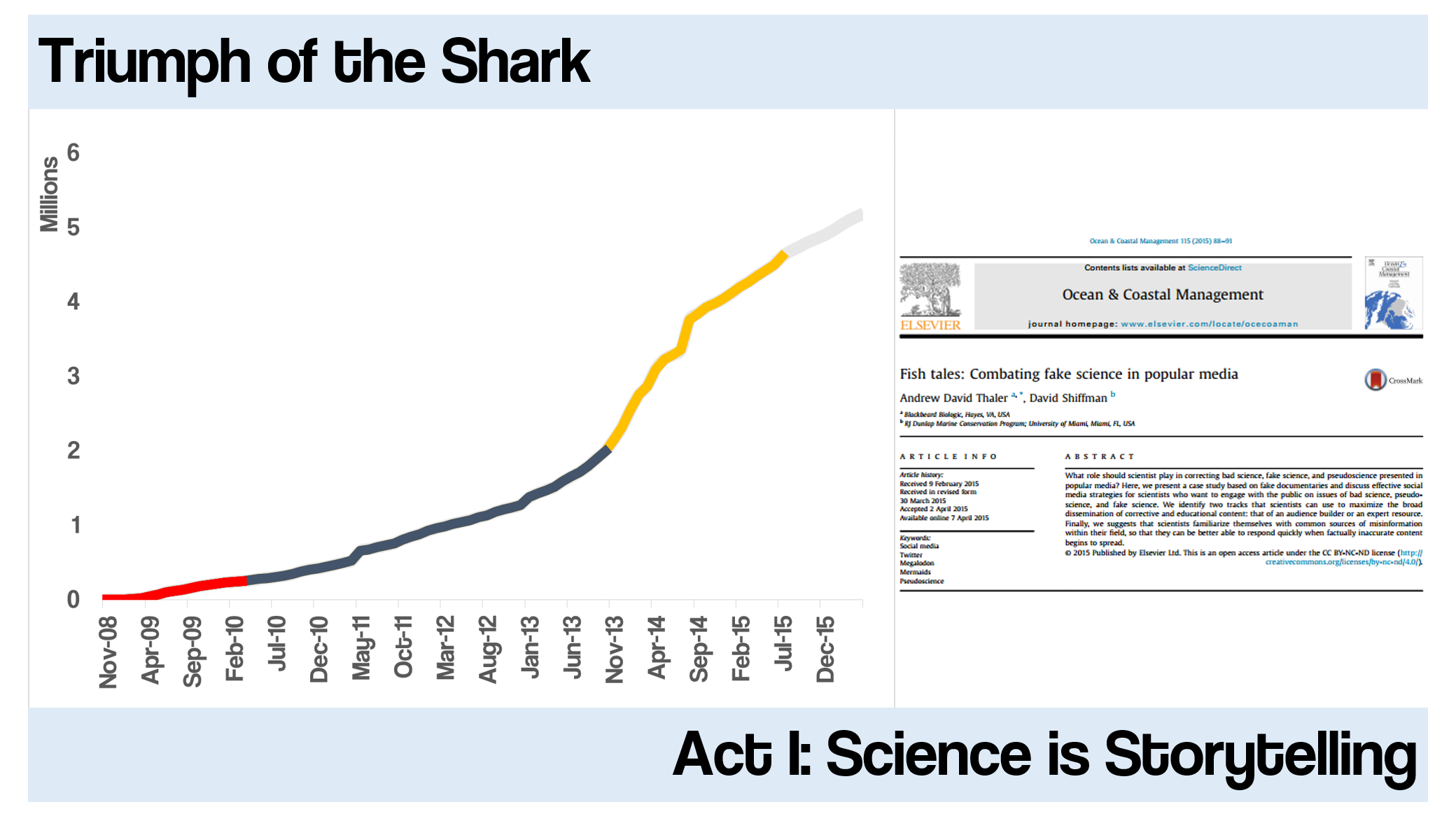

And it worked. At least for now and at least for Shark Week. Discovery issued a statement saying Shark Week would focus on more science-based and conservation-based messaging and would eschew the sensationalism and outright fabrication of its past programming. David and I have published this guide for scientists who want to engage with this kind of false or misleading presentation of their research, which I’ll link to at the end of this talk.

And that brings us to today and a new epoch in online outreach that is driven not so much by science blogs anymore but by social media platforms like Twitter, like Facebook, like Instagram, like YikYak and Snapchat and What’sApp, where the vast majority of our audience engagement now happens. This is true not just for Southern Fried Science, where we can see after a rapid ramp up during our battle against Shark Week our audience growth has tapered off but continues along at a respectable rate similar to what we saw during the Great Diversification.

We have, in essence, settled at last, into our ecologic niche.

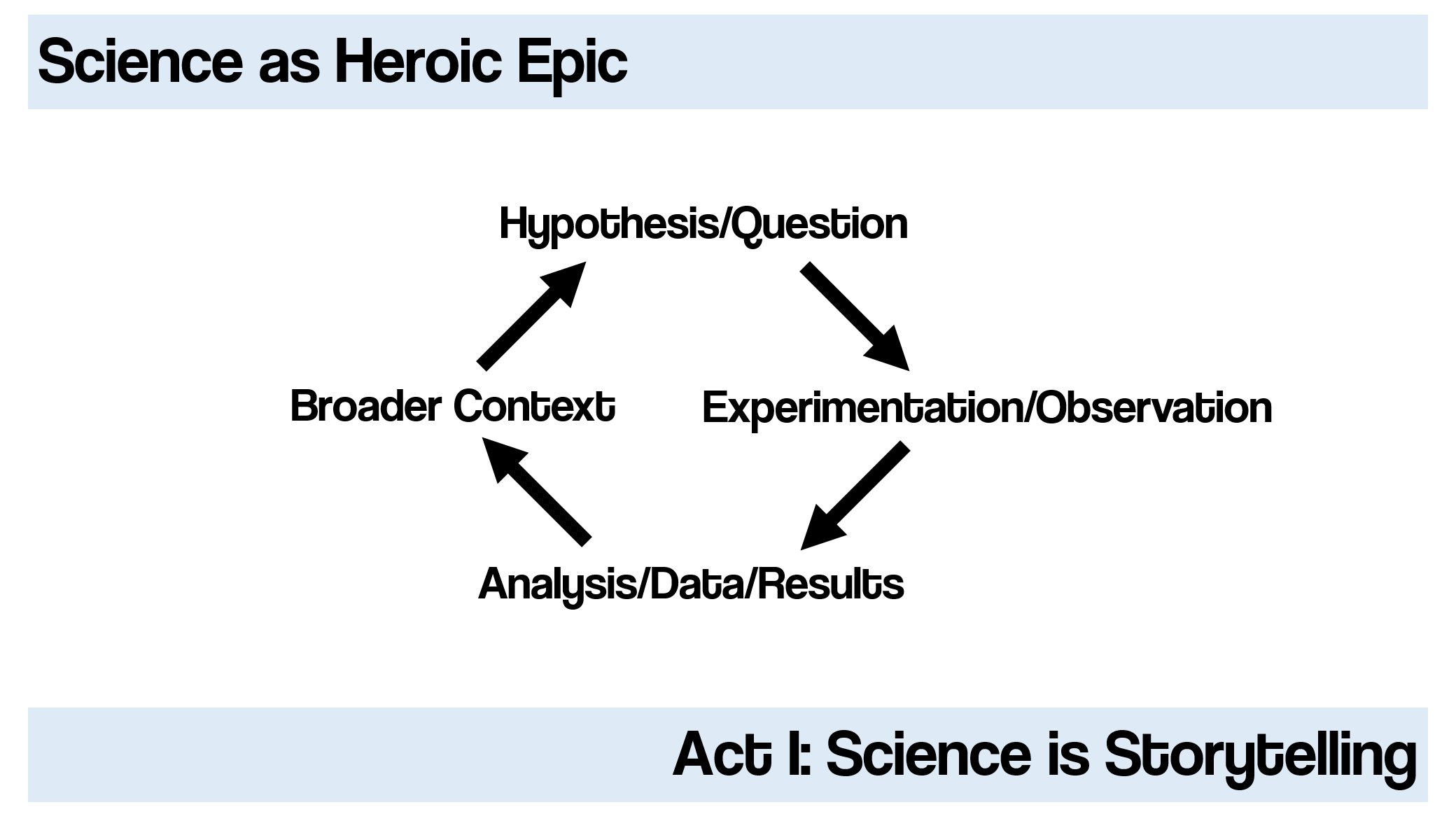

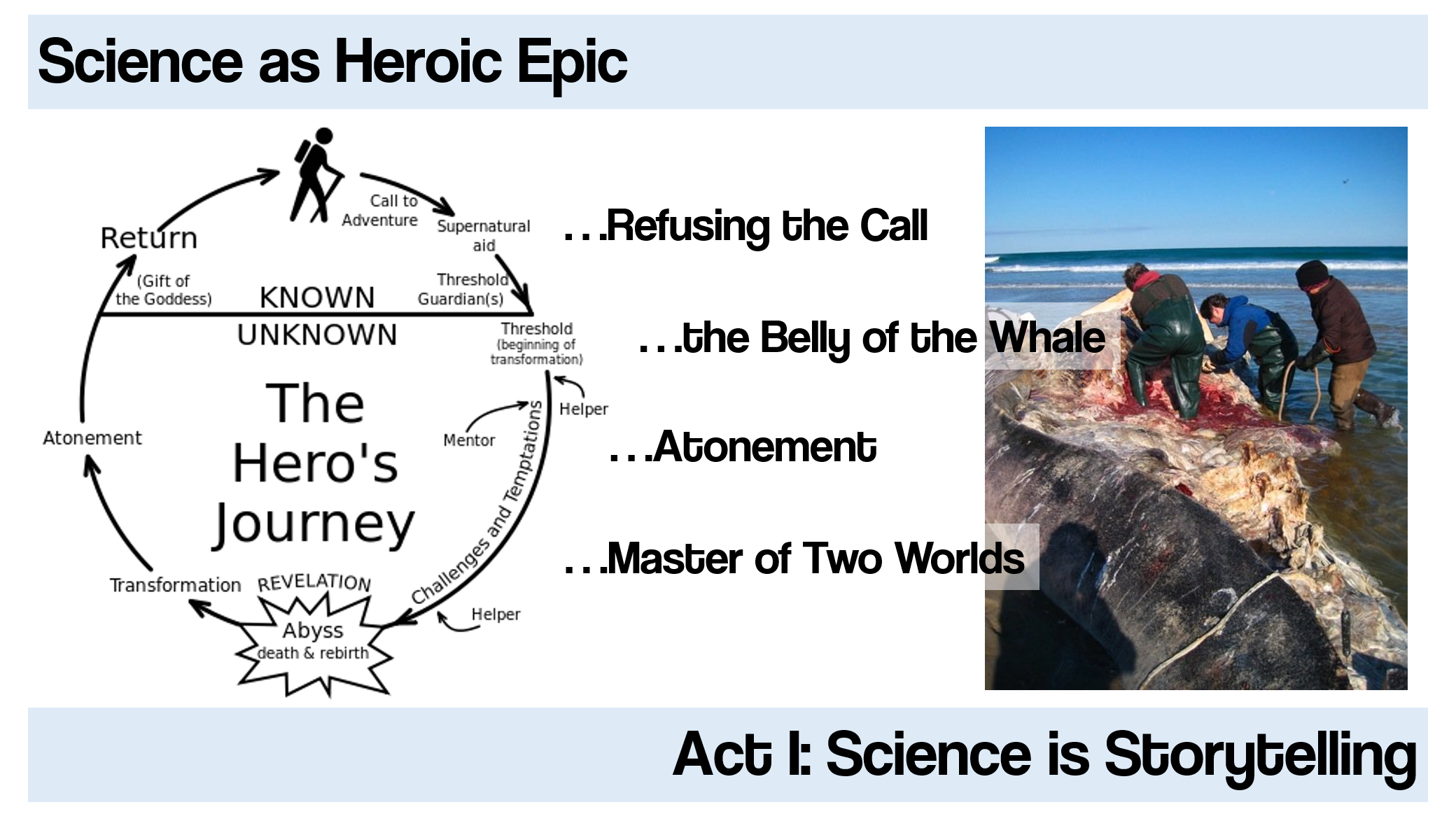

I just told you a story. It’s a true story. It’s a unique story. But structurally it’s a very common story. In fact, it’s the most common story. It’s Joseph Campbell’s Monomyth, the heroic epic. It begins with the hero’s call to adventure, a series of trials and tribulations, the conquest over their greatest foe, and a return home, wiser and stronger than before.

I just told you a story. It’s a true story. It’s a unique story. But structurally it’s a very common story. In fact, it’s the most common story. It’s Joseph Campbell’s Monomyth, the heroic epic. It begins with the hero’s call to adventure, a series of trials and tribulations, the conquest over their greatest foe, and a return home, wiser and stronger than before.

In Campbell’s Hero with a Thousand Faces, he outlined a detailed narrative structure, with multiple beats as the hero ventures from the known into the unknown and back into the known, including a refusal of the call–perhaps best characterized in the lab by loading a chunk of data and muttering “THAT can’t be right”; a plunge into the belly of the whale–for some of us more literal than others; a moment of atonement for past mistakes; and a return as the master of two worlds. These are incredibly common narrative beats in storytelling though not every story contains every beat.

Campbell didn’t invent this structure, by the way. He identified it as a common theme throughout literature, fable, and myth. And if this feels familiar to you, it’s because it’s Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, Iron Man, Moby Dick, The Martian, Jaws–it’s actually Jaws for both Quint, Hooper, and Chief Brody, and it’s also Jaws for the shark, who undergoes his own heroic epic– it’s Alien, Terminator, Mean Girls, Braveheart, and it’s just about every religious text.

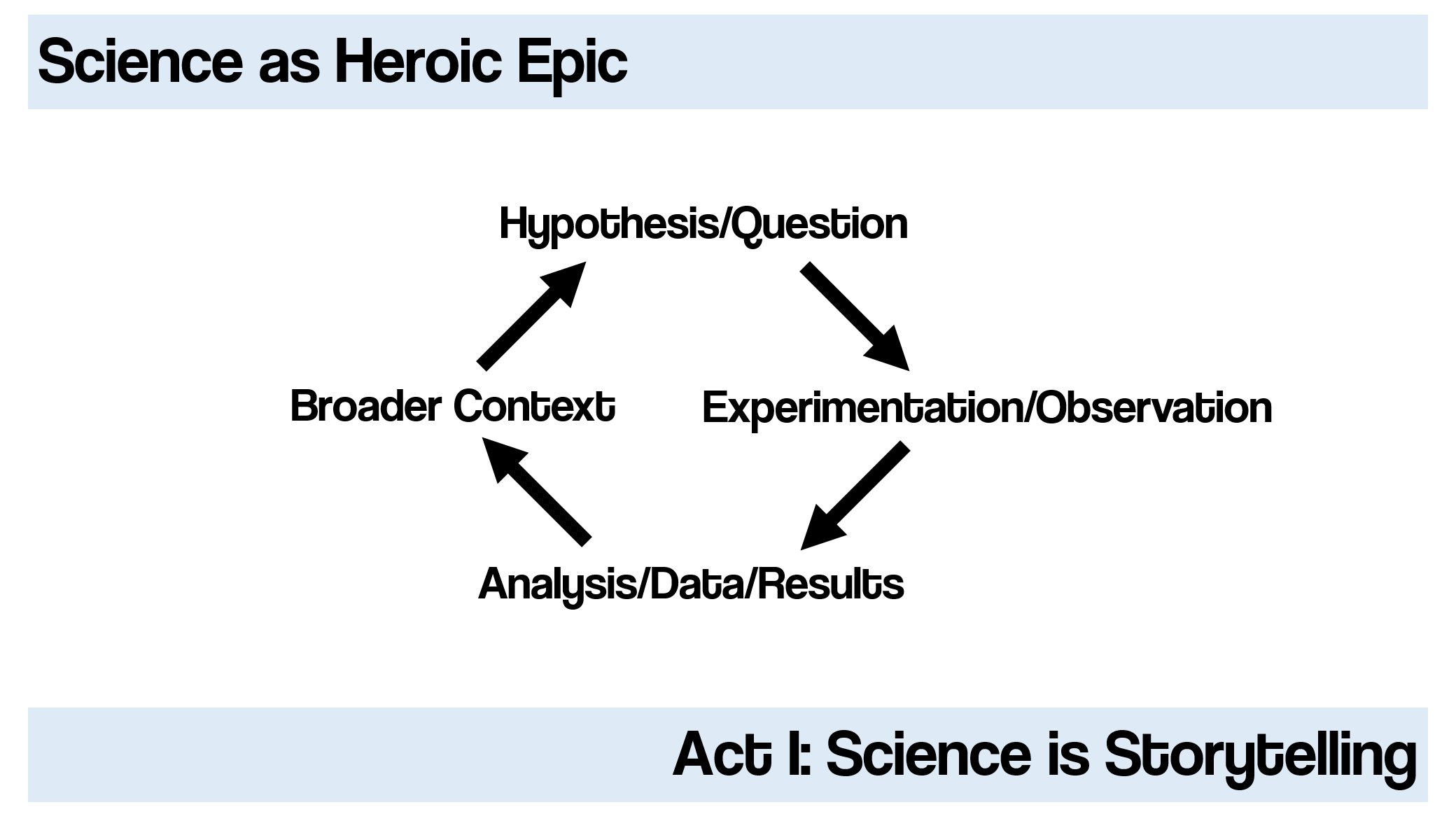

It’s also the narrative of scientific inquiry.

And how cool is that? The most common, the most effective, the most universal narrative device in storytelling also happens to be the conceit upon which we hang the structure of scientific inquiry.

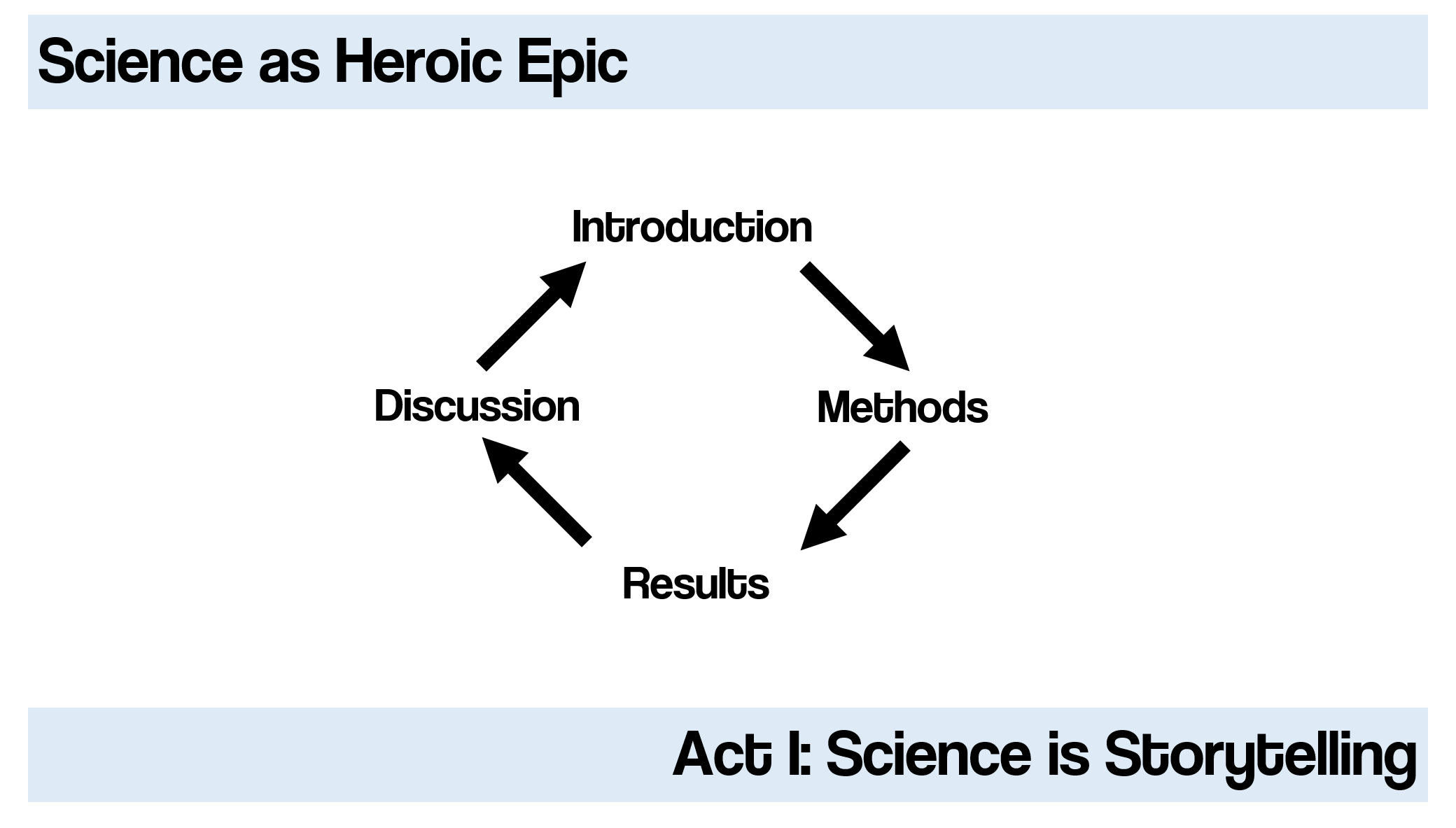

We even structure our publications around this framework. So don’t tell me that you can’t find a compelling story in scientific data, because the heroic epic is inextricably woven into every research paper. Every study has a story.

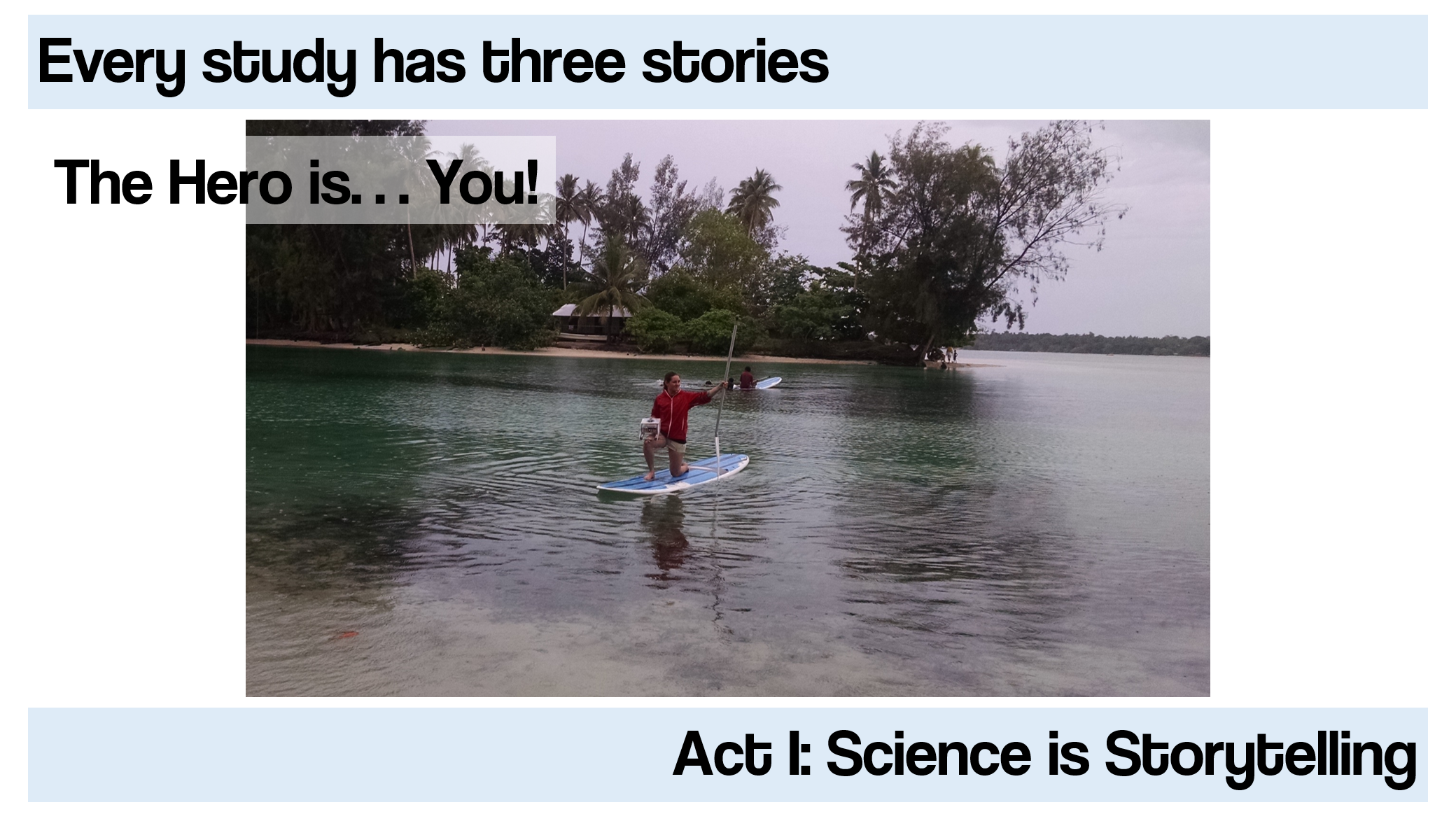

And actually, every study has at least three stories. And the story you tell depends on who you identify as the hero.

The easiest, most straightforward narrative is your own. No one knows the story of struggle and discovery better than the researcher, in the lab or in the field.

This is a picture of a colleague of mine, Erika Bergman, a National Geographic Explorer who, after getting a bachelor’s degree in oceanography, decided she wanted to pilot submersibles–call to adventure. Over the next few years, she became a submarine pilot, a self-taught electronics engineer, and a teacher-trials and tribulations. I met her through my work with OpenROV, where our shared love for adventure and education brought us to Papua New Guinea, where, along with a small team of technicians and educators from the local university and abroad, we led a month long course on Marine Ecology via Remote Observation, the first of its kind, anywhere in the world, where advanced undergraduates from the University of Papua New Guinea learned to build, operate, and maintain underwater robots and designed their own research projects around these platforms. The robots remained in PNG as assets for local scientists, and several of our students went on to become ROV operators–slaying the dragon. Erika returned to the US and founded Girls Exploration and Engineering Camps, where she now travels the country teaching young women about robotics–the return home.

I’m going to give you homework. You all have a story like this, and you’re doing yourself a disservice if you don’t write it down, so that the next time a reporter interviewing you about your latest study wants to know what you’re all about, you’re ready to share an adventure with them.

But you are not the only story there is to tell because the science itself tells a story.

This is the dry lab on the R/V Blue Heron, a UNOLS vessel that lives on Lake Superior. What you’re looking at is an underwater robot, sampling equipment like Niskin bottles and a CTD, and, in the very back there, a 3D printer, which you can use to manufacture equipment while at sea. These are all open-source tools that empower people to design, build, and operate their own research equipment-call to adventure. They are part of a suit of gear under the aegis of Oceanography for Everyone, that makes the tools of marine science available to anyone interested. This was their shakedown cruise–the trials and tribulations. The CTD, which cost all of $200 to build, performed within a 2% tolerance of the $60,000 commercial CTD that Blue Heron carries–slaying the dragon. As more of these are built, more citizen oceanographers can explore their world, unburdened by the weight of a research grant–return home.

By making the story about the science, itself, your audience gets to sit in the captain’s chair. When a story is about a particular person, the audience watches that person on their journey, but when it is about the science itself , the audience gets to assume the identity of the protagonist and engage with the story as if it were their own.

And the reason I know this is true is that, right now, probably a quarter of you are imagining what you could do with a robot, a suite of cheap sensors, a 3D printer at sea.

The last story is the most challenging to tell. It’s a process story, about how scientific knowledge travels from the minds and notebooks of the researcher to the public consciousness. Whether it’s about scientists being stifled by the Harper government, or a research paper that was clearly forced through peer review before the study was really ready, or just the fact that major conservation journals don’t think that marine papers are of a general interest; these are stories that need to be told and they’re challenging stories to tell. Though it may be hard to see, these stories still follow the arc of the monomyth and there is still narrative structure within them.

But let’s step back for a minute because we just went deep into the weeds. The reason I’m highlighting these three heroes in science storytelling is not because I think you need to tell all your stories but to help you identify where the most compelling stories are. Maybe you’re not the best hero for this story. Maybe the process of discovery in the laboratory involved sitting and pipetting a clear liquid into another clear liquid ad nauseam for 6 years and that’s fine. That is a story that you could tell but it’s not a story that will be particularly compelling. Maybe the process was you submitted it to peer review, you got some comments back, you made the changes, and then 6 months later it was published. That’s a story, but it may not necessarily be the story you need to tell. But by understanding the underlying narrative structure behind storytelling, you can use the heroic epic as a guidepost to find that compelling moment, you can find the story within your study that people want to hear. The story that needs to be shared and that you and only you can tell well and tell effectively.

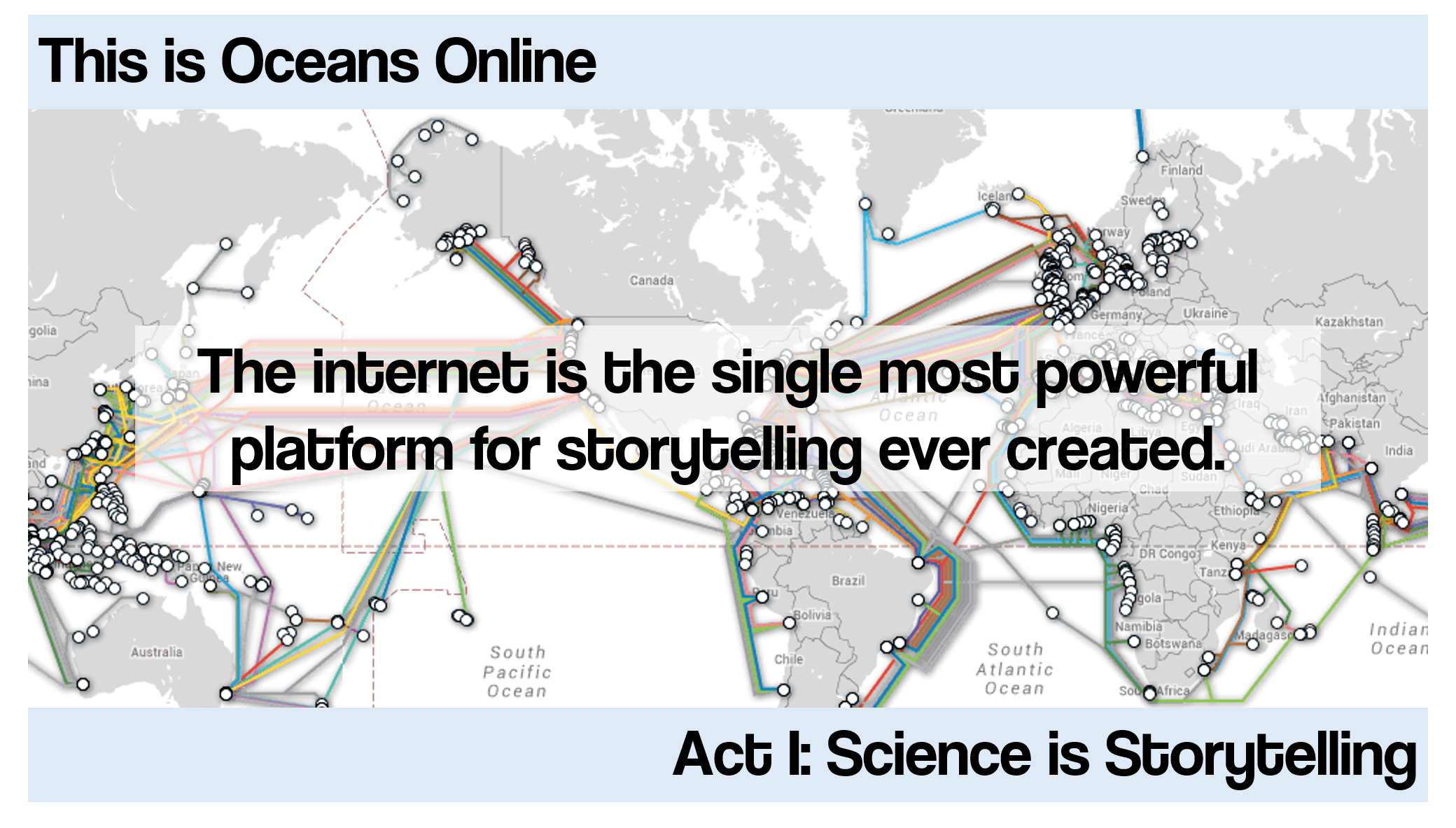

So this is Oceans Online. This is literally oceans online. This is a map of all of the sub-sea cables that stretch across the ocean and connect the world’s telecom infrastructure. This is the internet. It’s a real thing. It’s a physical network. And it’s the single most powerful platform for storytelling ever created. It gives you the power to reach a massive global audience to reach people that would otherwise never engage with scientific or conservation content, to discuss and share ideas and innovations with stakeholders around the world. This is the reason we’re here at Oceans Online.

So let’s have an adventure.

I’ve only read Act 1 so far and I want to applaud. This is incredible.