This is the transcript of the keynote I delivered at the Fourth International Marine Conservation Congress in St. John’s, Newfoundland. It has been lightly modified for flow.

Read Act I: Science is Storytelling.

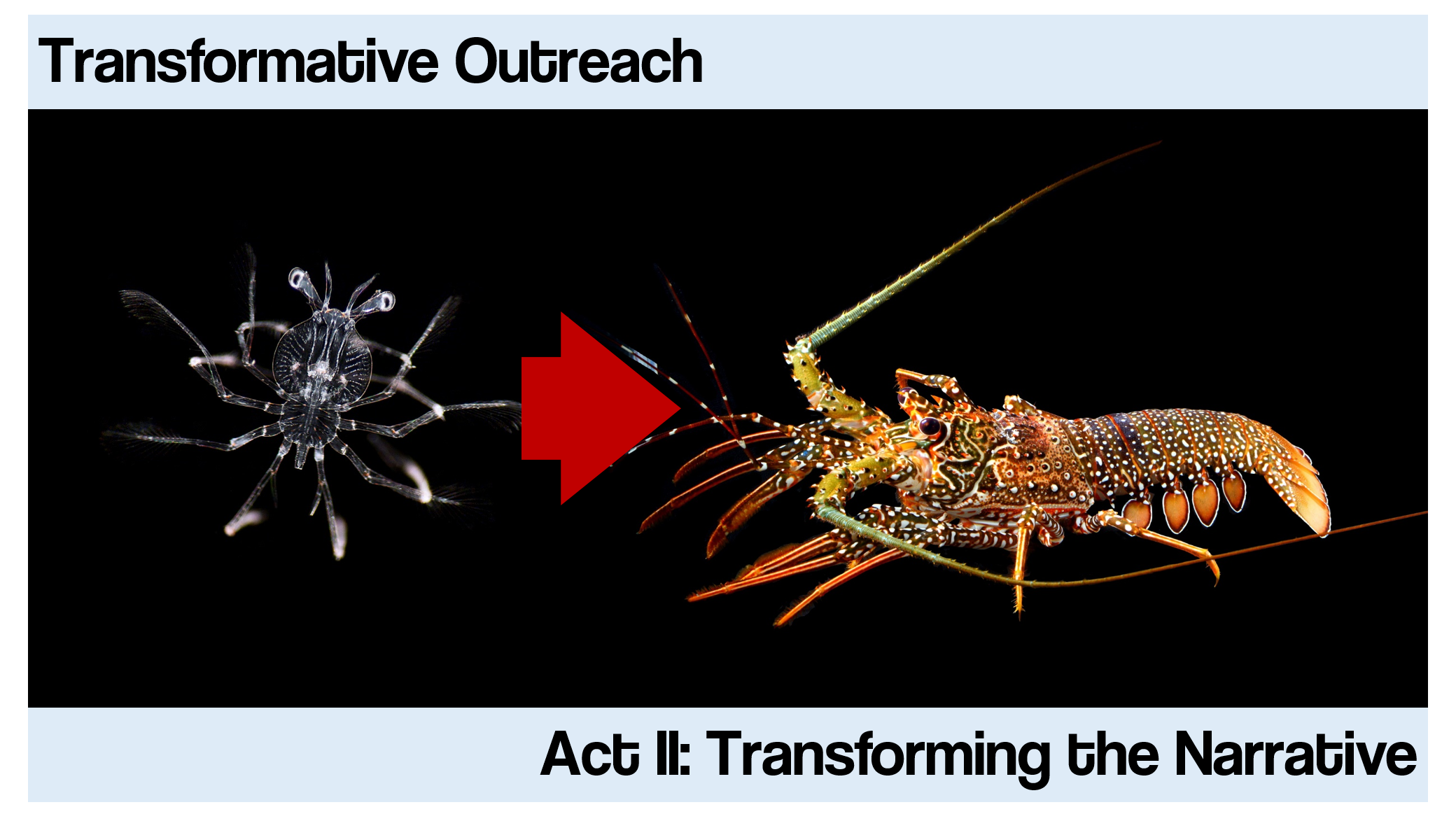

In Act I I discussed the underlying structure that frames narrative storytelling, but now I want to talk about how we can use the tools available to us on the internet to transform that narrative into something even more potent.

But before we can do that I have to tilt at some windmills.

When we talk about good outreach, we often look to people like Neil deGrasse Tyson, like Bill Nye, like David Attenborough, and like Carl Sagan. These are the paragons of scientific outreach, the icons that we often hold up as examples for what constitutes good outreach. We talk about things like Cosmos, both Sagan’s and deGrasse Tyson’s, Bill Nye the Science Guy and his more recent work combating climate change, or David Attenborough and his astounding Nature Documentaries.

But I’m going to ask you today to think a little more quantitatively about outreach, about the hypotheses we can postulate regarding effective outreach, and about what phrases like “good outreach” really mean.

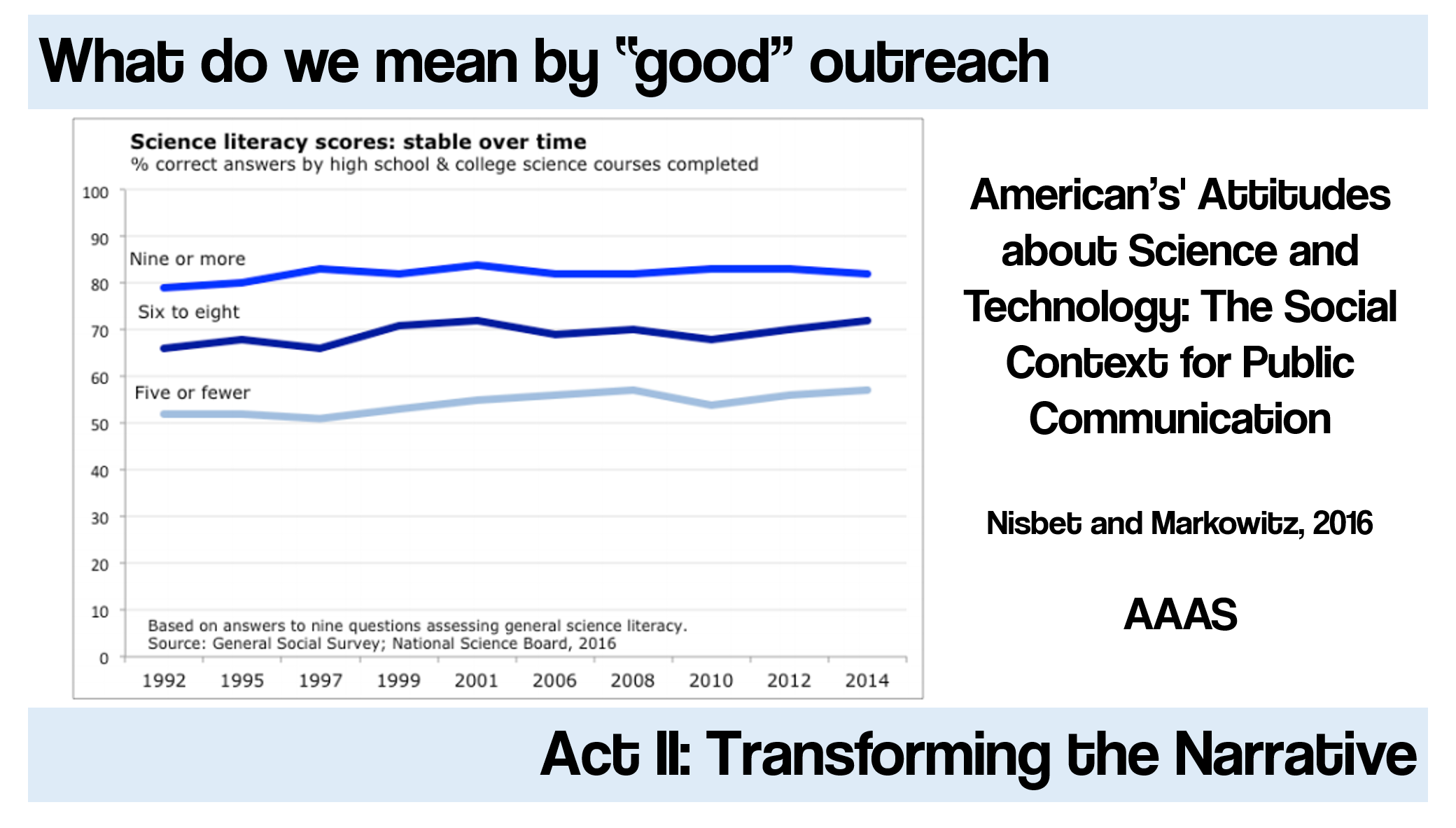

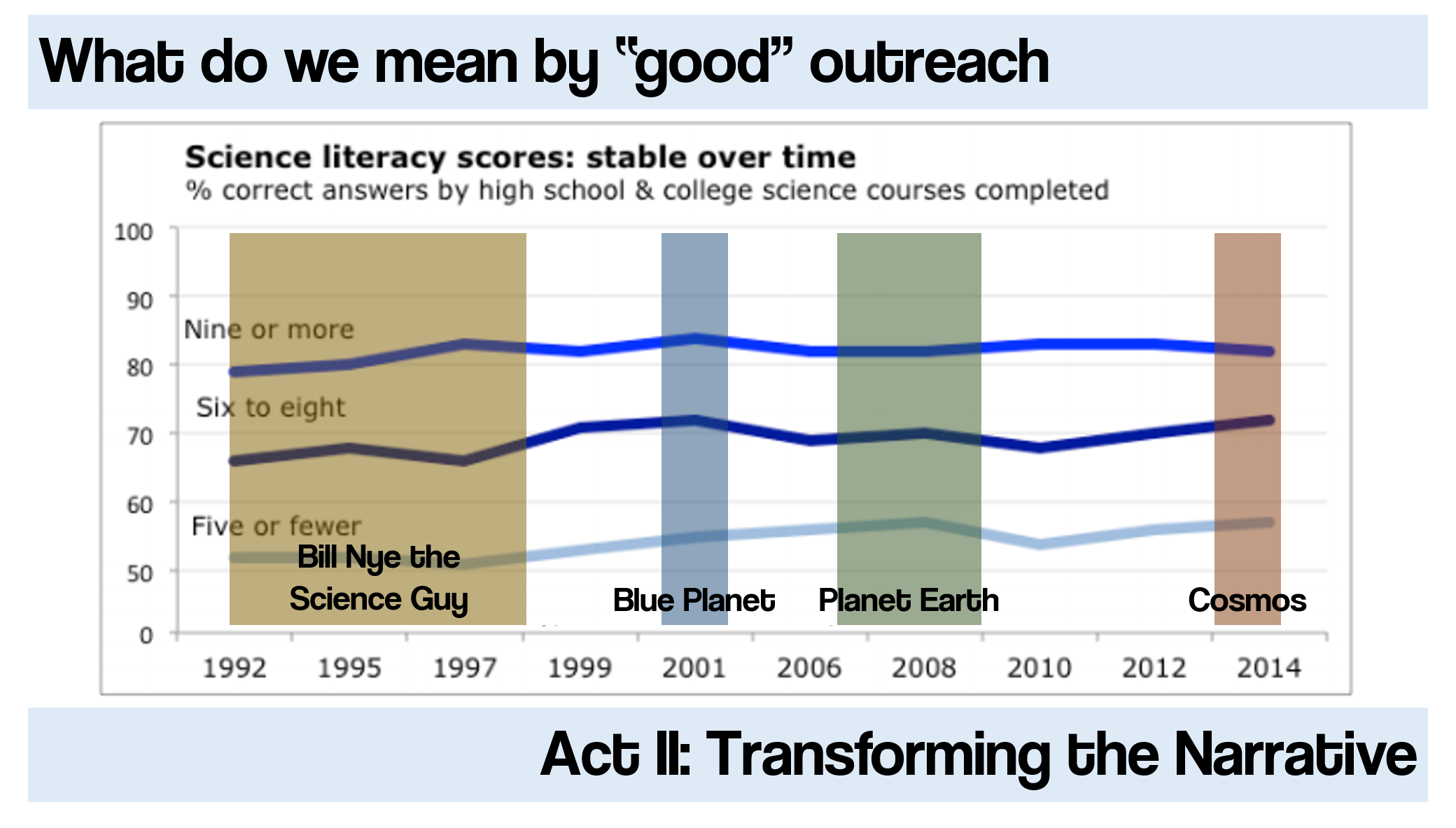

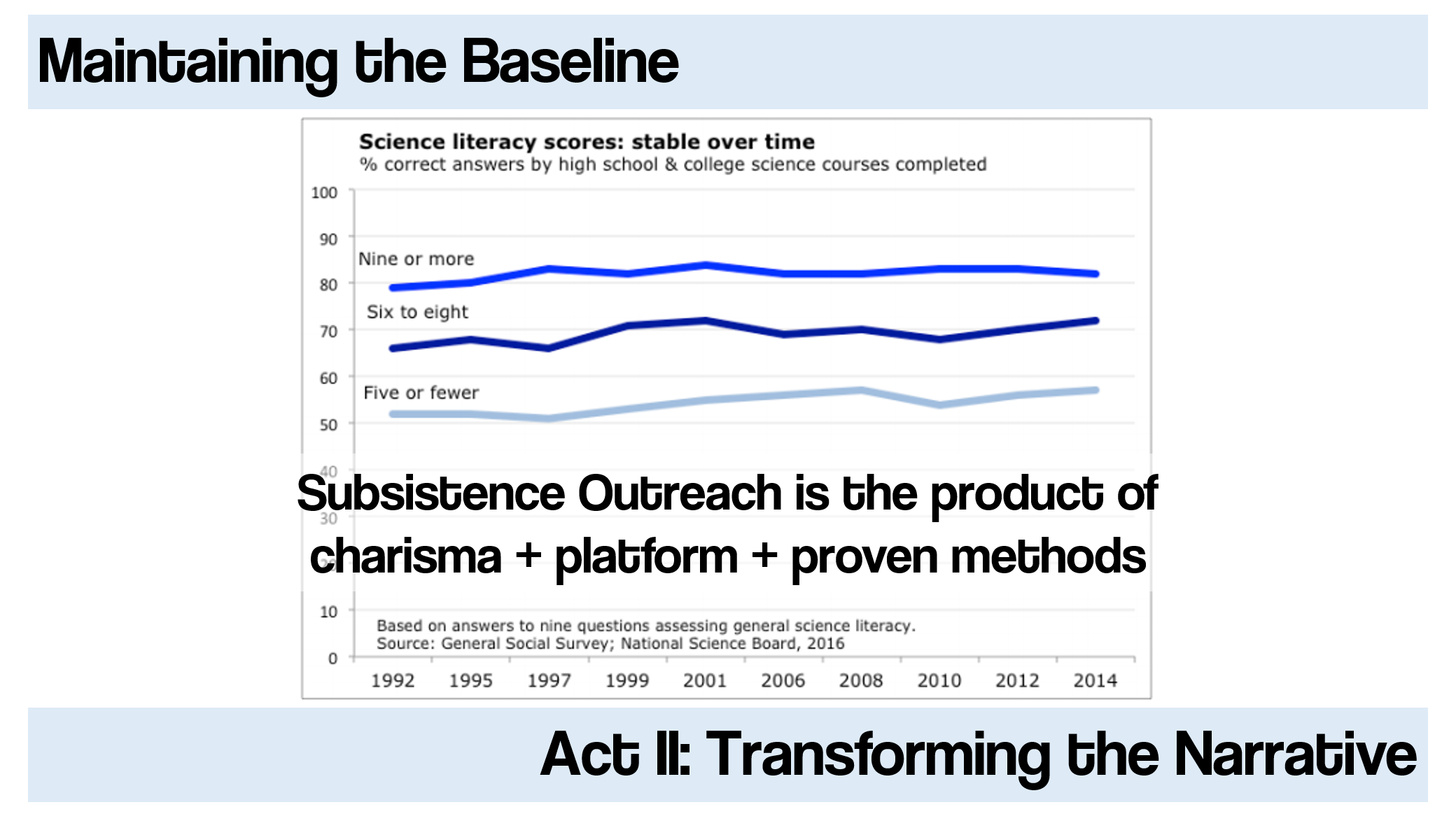

So here’s a hypothesis that we can test. The best outreach results in an increase in general science literacy over time. And we have data that we can use to test this hypothesis. This graph is from a AAAS report that came out this year. This is a fantastic broad-ranging report about Americans attitudes toward science, the breadth of which I’m only going to very lightly touch on during this talk, but if anyone is interested in really digging deep into the data about science communication I’ll have a link to the report at the end.

So we know from this 20 plus year longitudinal study that in general science literacy has really been stable over the last two decades.

And when we overlay some of these big watershed moments in popular media, in science outreach, in science communication: Bill Nye’s show, Blue Planet, Planet Earth, deGrasse Tyson’s Cosmos we see that the actual impact on general science literacy is insignificant.

So what’s going on? Am I saying maybe some of the best science celebrities we have at our disposal are perhaps not really as effective communicators as we’d like to think? No, not exactly, not at all, really. I adored every single one of these shows and I’m willing to bet that most people in the audience also loved them. These are great sweeping, awe-inspiring moments in science communication.

But I am suggesting that perhaps we invest the bulk of our energy into getting people who are already excited about science more excited about science. General Science literacy is remaining stable not because our outreach is ineffective, but because the audience we’re targeting already is science literate.

We’re preaching to the choir. And you know what? You should preach to the choir because preaching to the choir is how you get the choir to sing. But preaching to the choir is not going to bring more parishioners into your church. It’s not going to grow your audience unless you have a rare and truly exceptional choir, but it will maintain your audience. If the choir sucks people are going to go sing at the church down the road.

What we’re doing is we’re maintaining the baseline.

This is what I call subsistence outreach. It’s the most common outreach we do. It’s among the most important outreach we do but it’s about maintaining a basic level of science literacy. And it’s formulaic. We know what kinds of audiences these productions attract we know who is going to engage with this kind of outreach we can predict how large the audience will be and we can plan for it. It’s a proven method and it is effective for maintaining that baseline.

And that’s great you know most of us here will only ever really do subsistence Outreach. most of what we do through Southern Fried Science is subsistence outreach, but I have a challenge for us all. Since we are sitting on the single most powerful platform for storytelling ever created, and we’re at a gathering of some of the best ocean science and conservation communicators ever assembled, let’s think strategically about how we can take the proven methods of subsistence Outreach and the nearly unlimited potential of an online ecosystem and transition into transformative ocean outreach.

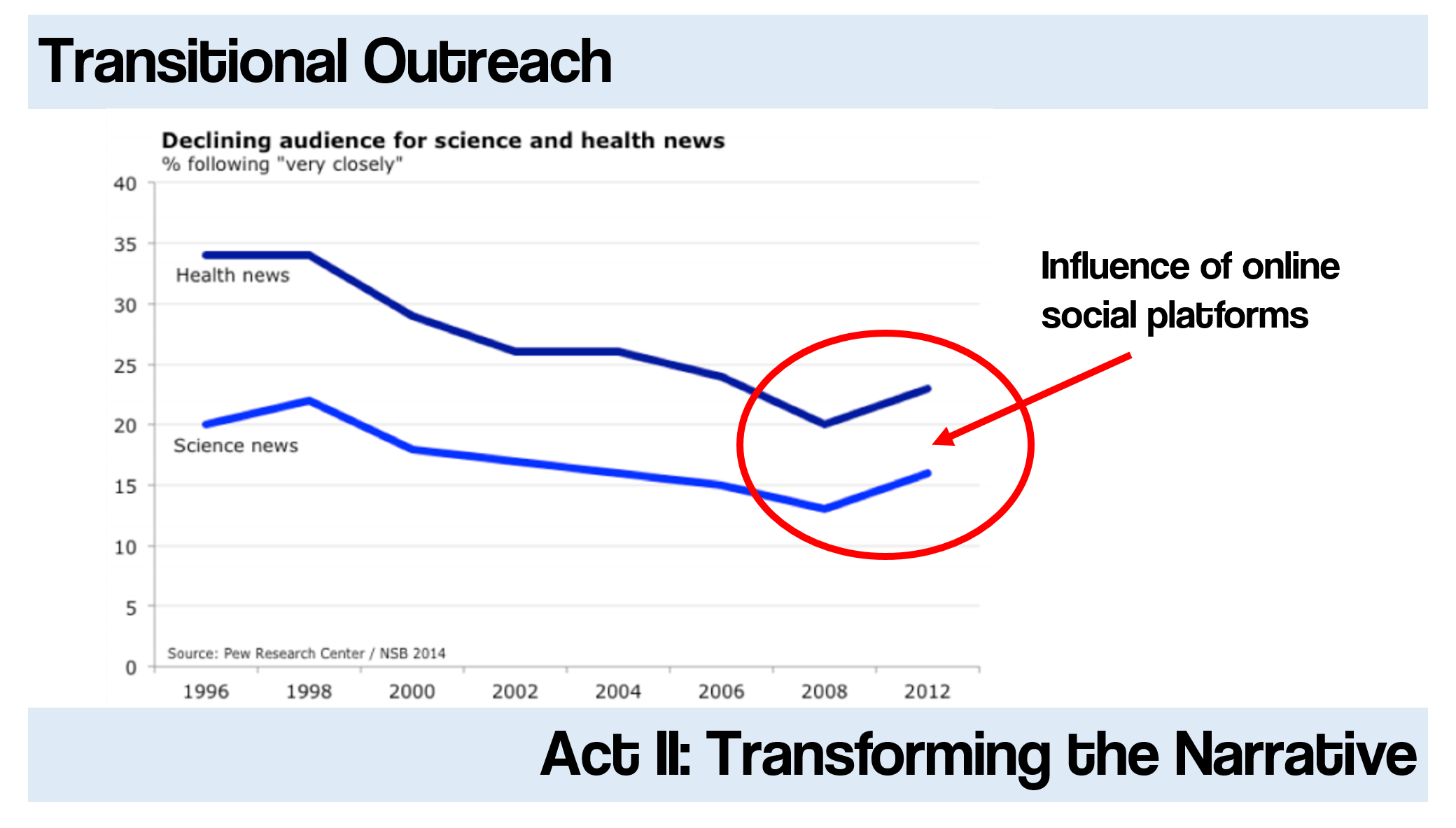

So there’s good news and bad news. While overall science literacy has remained stable, the actual audience for science news has shrunk over the last two decades. So, in reality, fewer people are engaging with science content at a deeper level.

But around 2008, something changed, and what changed is the advent of the smartphone, the rise of social media platforms, like Twitter, and a fundamental shift in how people access news. Today more people get their news from Facebook than from the New York Times. People trust their friends more than the talking heads on CNN. And you could interpret this as a problem, but you can also see it as an opportunity. An opportunity to grow the ocean science audience.

This is something I call transitional outreach, outreach designed specifically to grow the audience, rather than simply maintaining the baseline, using conventional approaches to outreach while taking advantage of new platforms and new potential audiences. So I have a system for you. It’s a method I’ve developed over the last 8 years running Southern Fried Science. So rather than everyone trying to reinvent the wheel with every new outreach campaign, you can take our experience, you can take our failures, you can take our successes…

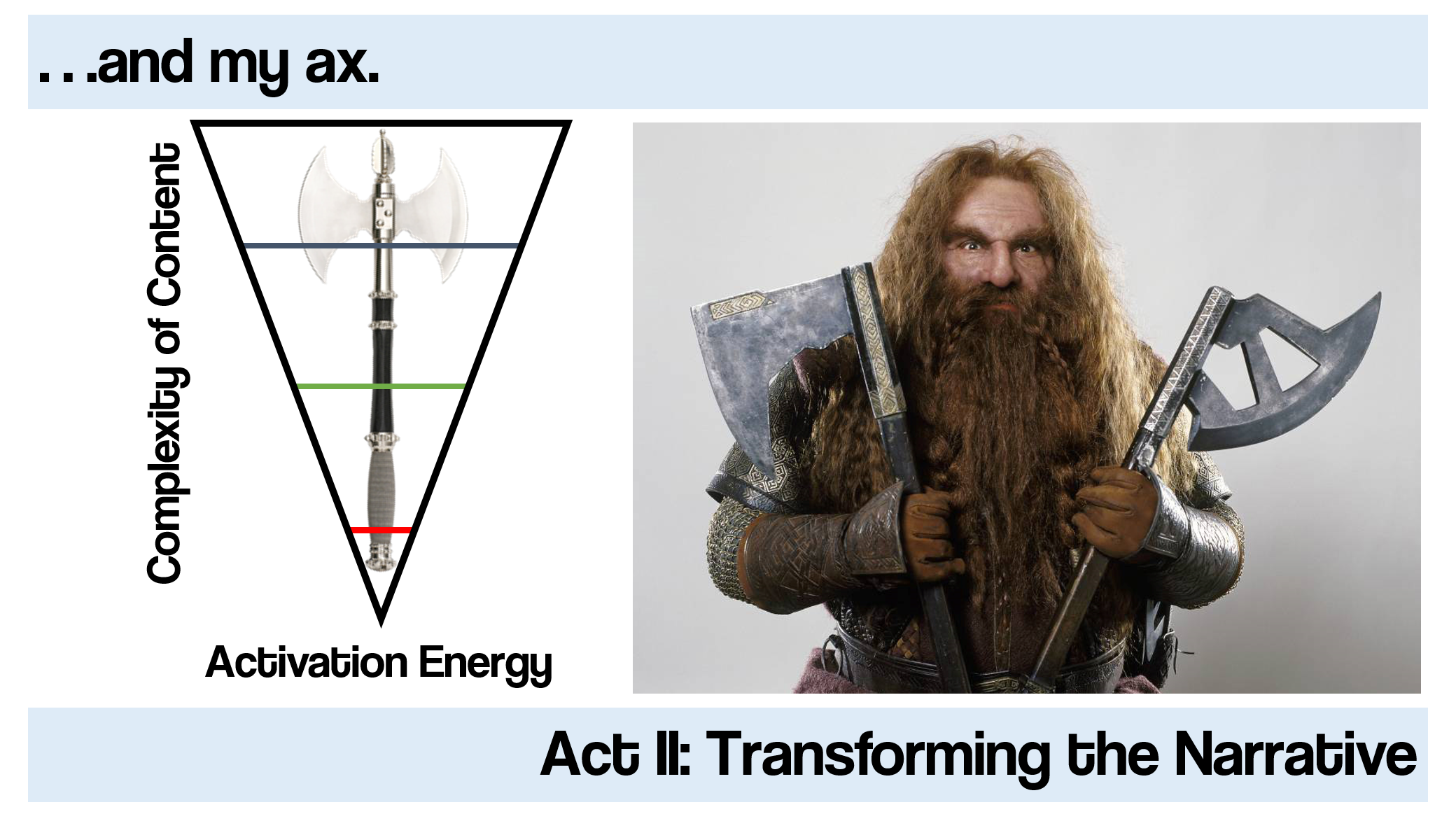

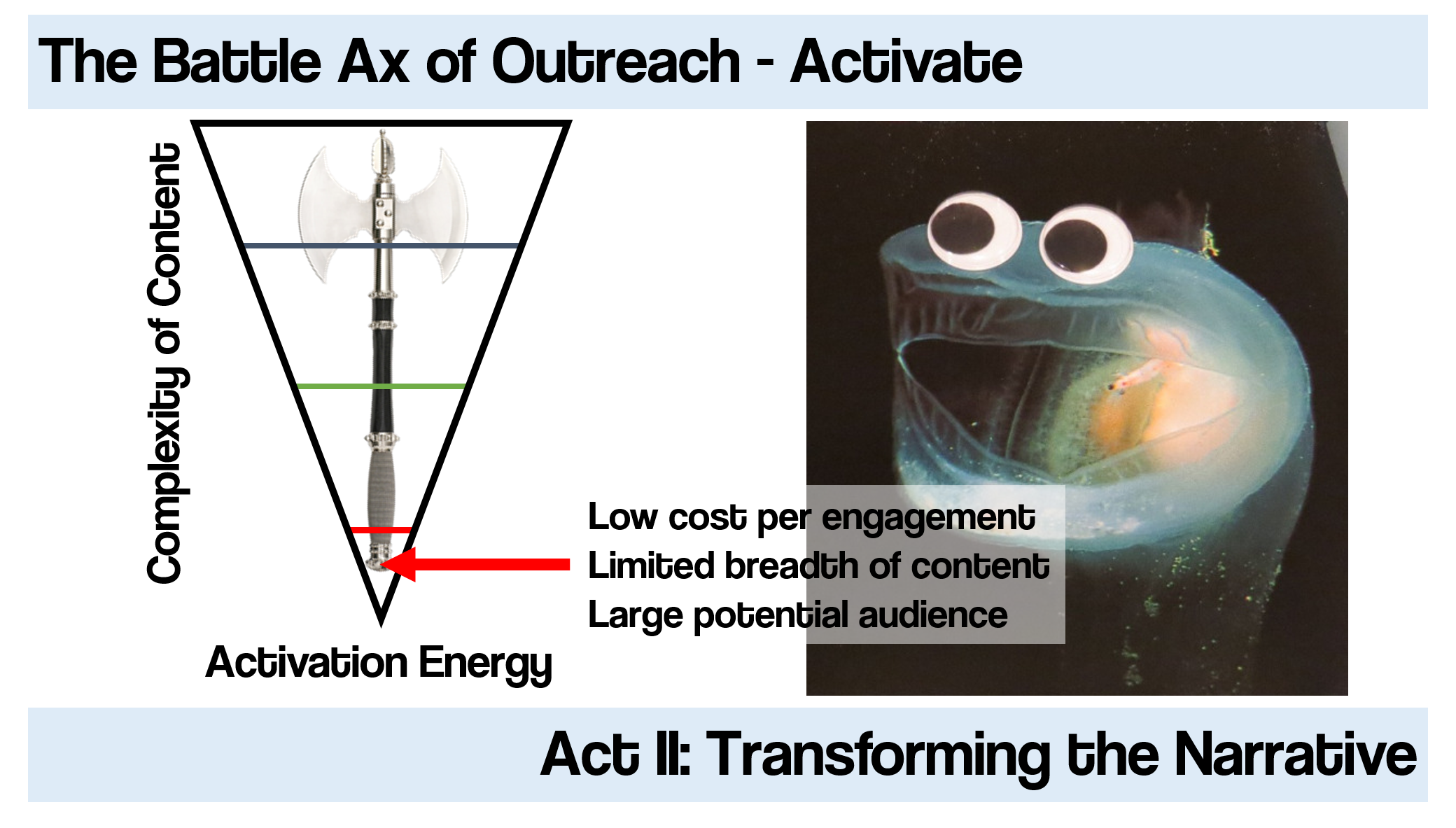

And you can take my ax. This is what I like to think of as the Battle Ax of Outreach. It’s a set of guidelines for thinking about how you approach an ocean outreach campaign. If you think of the ax as a graph (because it is a graph), the x-axis is activation energy, the amount of effort you audience needs to expend to engage with your campaign. The y-axis is the complexity of the information you want to share.

Think about swinging an ax to split a log. An ax head has an edge, cheeks, a wedge, and a heel. And all these faces work together to split a piece of wood. The edge gets the cut started, the cheeks and wedge push things apart, and the heel gives the ax most of its mass. And effective outreach can work the same way.

Step 1. The edge of your ax. The activation phase. This is the content you create to draw in an otherwise uninterested audience. It’s the fun bit, the goofy bit, the part that doesn’t require your audience to expend a ton of energy. The content isn’t particularly complex, but the cost per engagement is low and the potential audience is huge. This is the stuff that goes viral. And it can be something ridiculously simple, like putting googly eyes on deep-sea fauna. That website, by the way, got almost four million unique visitors the week it launched and it continues to be our most trafficked site.

Step 2. The cheeks. The expansion phase. This is where you begin pushing that wood apart. This is where you take that audience you’ve attracted from the activation stage and introduce them to slightly more complex information. Talk about the science behind a particular googly-eyed deep-sea animal. If, for example, you’re running a climate change campaign called DrownYourTown, let people request specific regions for you to generate sea level rise models, and talk a bit about the science behind it.

Now,you’re not going to keep your entire audience from the activation step. One of the caveats of this system is that the further up the ax, the smaller the audience, but if you do this well, you’ll retain far more than if you had just launched a campaign with a blunt edge.

Now that you’ve got an activated audience that you’ve locked in with some deeper content, it’s time to engage. This is the wedge. The most effective piece of the Ax. Engagement content is tailored towards more one-on-one or one-to-few interactions. You’re reaching out directly to your audience and bringing them into your project. Think about things like, for example, taking interested stakeholders out on a shark tagging boat. In one sense, they’re participating in your project, but really, the experience is tailored for them and the goal of taking them out isn’t to get an extra set of hands, but for them to interact with researchers. The potential audience for this is, well, very small. There’s only so many people you can personally work with at a time, but the potential for creating a committed, enthusiastic new member of your community is tremendous.

And, most importantly, it allows you to feed into the final phase.

The final phase. The heel of the ax. Empowerment. There are two ways to think about this depending on the goals of your outreach. The heel is the dense mass that provides the inertia behind your initiative. It’s the rigorous peer-reviewed science that lends gravity to the rest of your campaign–and yes, publishing peer-reviewed papers is a critical component of science outreach.

But it can also be something else. The empowerment phase is the point where you take your core audience and you transition them from consumers to producers by giving them the tools to carry the outreach campaign, no longer just *your* campaign, further. For something like DrownYourTown, it was releasing the apps to create sea level rise models, and inviting people to generate their own. This led to some new and fascinating creations, including a way to simulating flooding after a dam broke and a series by the Weather Channel on what national monuments would look like after sea level rise.

This is participant-driven engagement, where a small but committed team is producing new material and reaching new audiences, starting the cycle over again. Doing this well means giving up some control over the campaign, but it can lead to surprising and unexpected new opportunities.

An ax works best when you have all the pieces-the edge, cheeks, wedge, and heel. Outreach that is all heel is a hammer. Sure, you can pulverize a stump into submission with it, but it will be mostly wasted effort. Outreach that’s all edge is a machete. You might be able to split a log, but you probably won’t, and more than likely you’ll end up hurting yourself and breaking your tools in the process. The trick to good, transitional outreach that grows an audience is to build a good ax and then implement it well at all phases, with a strong, straight swing and consistent follow-through.

That’s the model I’ve used at Southern Fried Science for almost a decade, and it has served us very well.

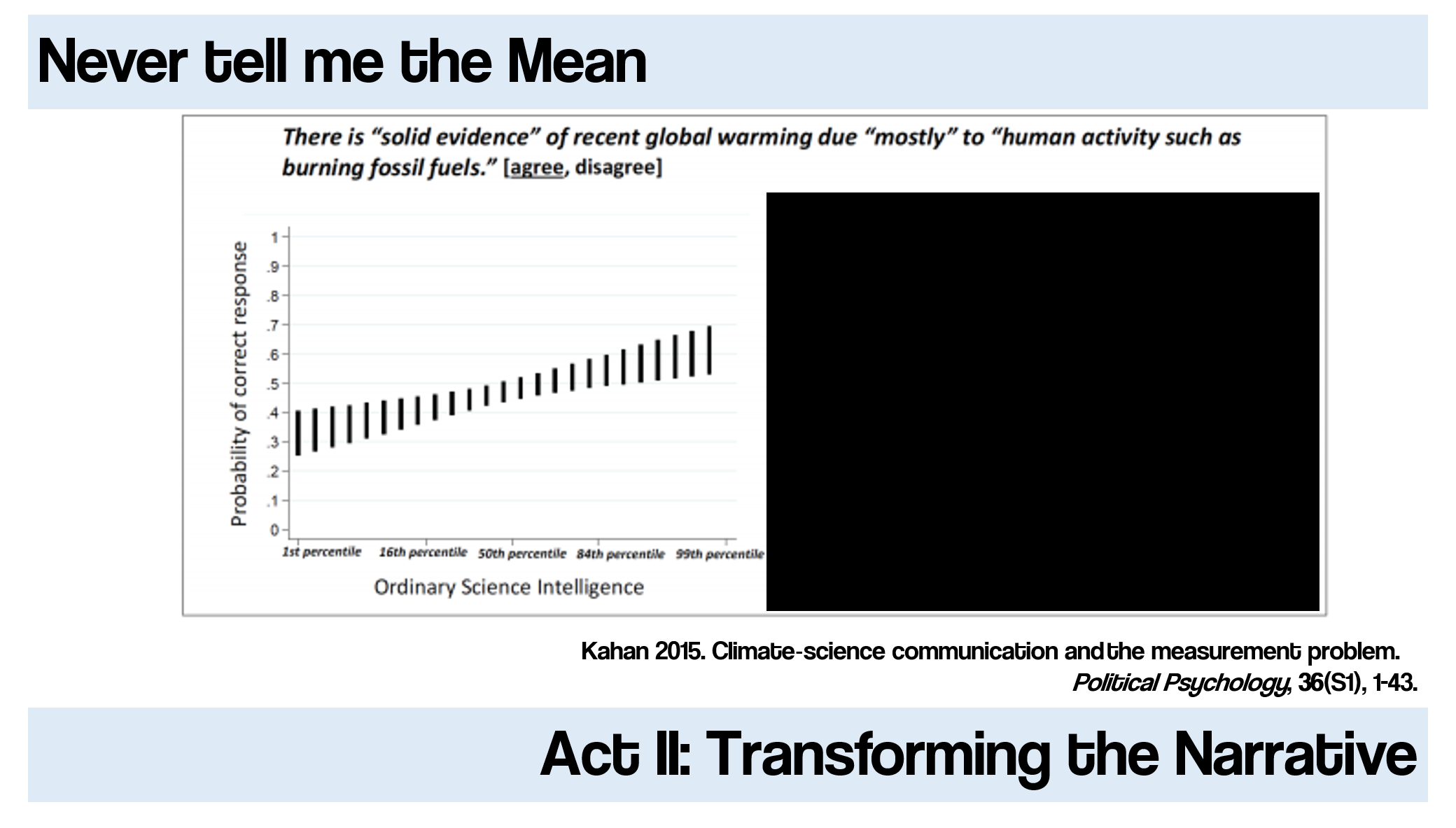

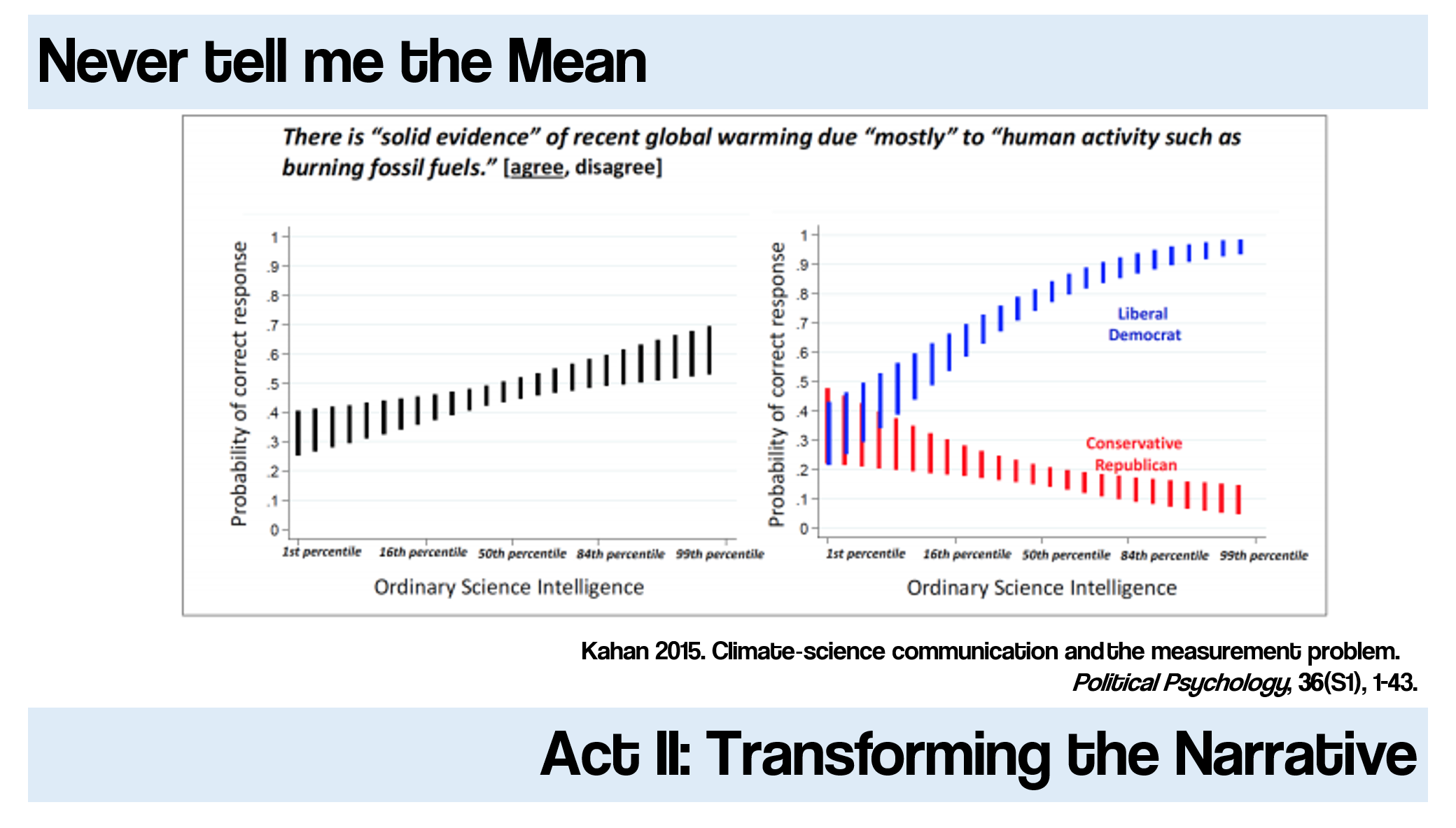

But even a carefully crafted outreach campaign isn’t going to accomplish anything if you don’t understand your audience. If we look at ordinary science intelligence–which is another way to think about science literacy–and look specifically at how it relates to something like the acceptance of Climate Change among the American public, we might think ok, well, as science literacy goes up, so does acceptance of manmade climate change. So climate change is a science education problem. It’s the deficit model.

But that’s not true. Because if we break the audience out into self-identified political ideologies, we find that as science literacy goes up among self-identified liberals, acceptance of climate change climbs to almost 100%, but among self-identified conservatives, the more science education you have, the less likely you are to accept man-made climate change.

Now, I’m not here to dump on liberals or conservatives, and I’m not here to talk about climate change. But what I’m trying to show you is that if you just look at broad, general statistics about your audience, you miss some extremely important trends that should inform and shape all of your outreach. There’s a message in this data, and that message is…

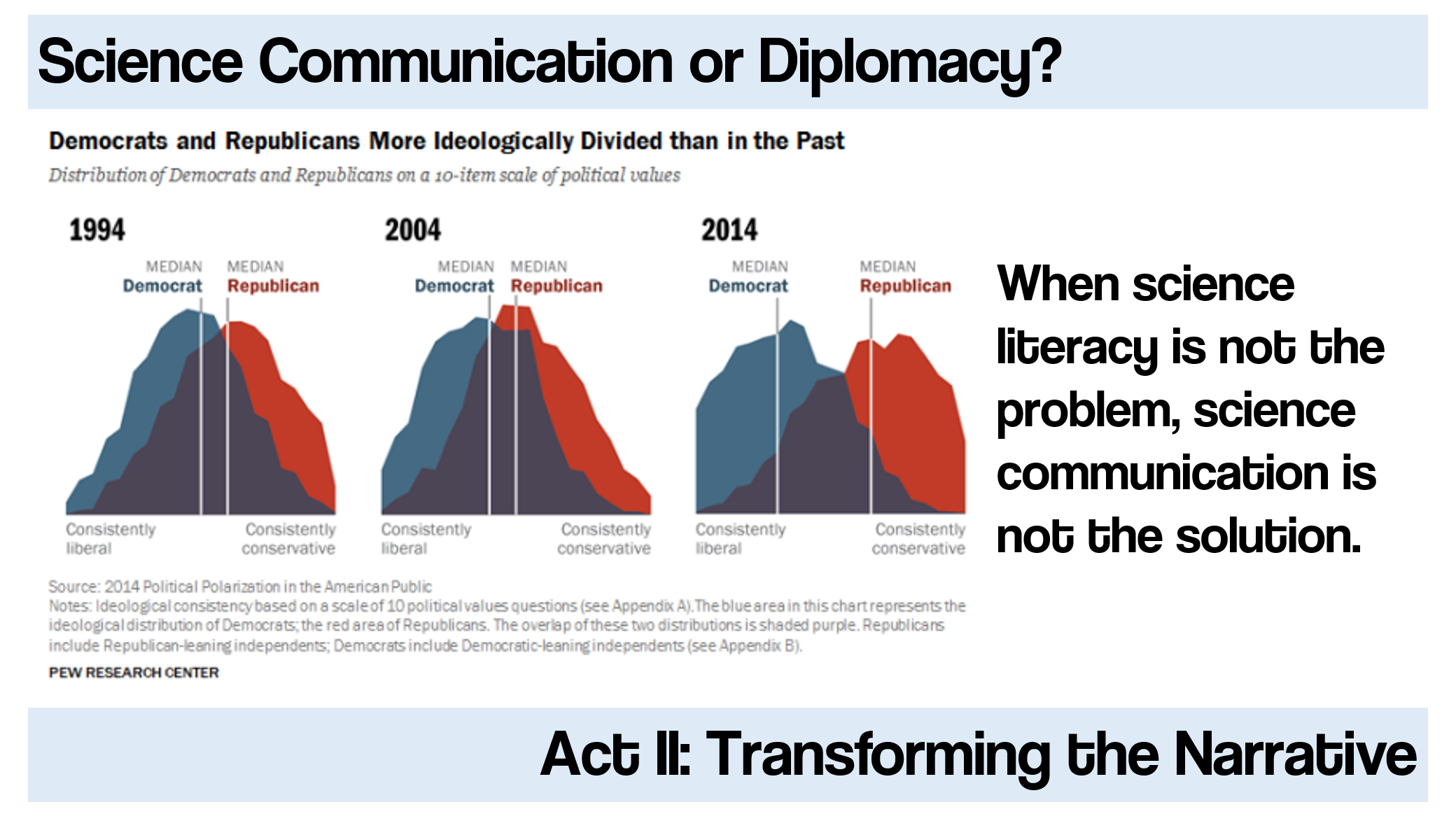

That rejection of climate change is not a science communication problem. It’s a problem of increasing political bifurcation among the American public. Increasing science literacy is not going to increase the public acceptance of man-made climate change, and if your target audience is strongly conservative, science outreach could actually reduce climate change acceptance.

When science literacy is not the problem, science communication is not the solution.

The solution is to do something novel. The solution is to transform the narrative.

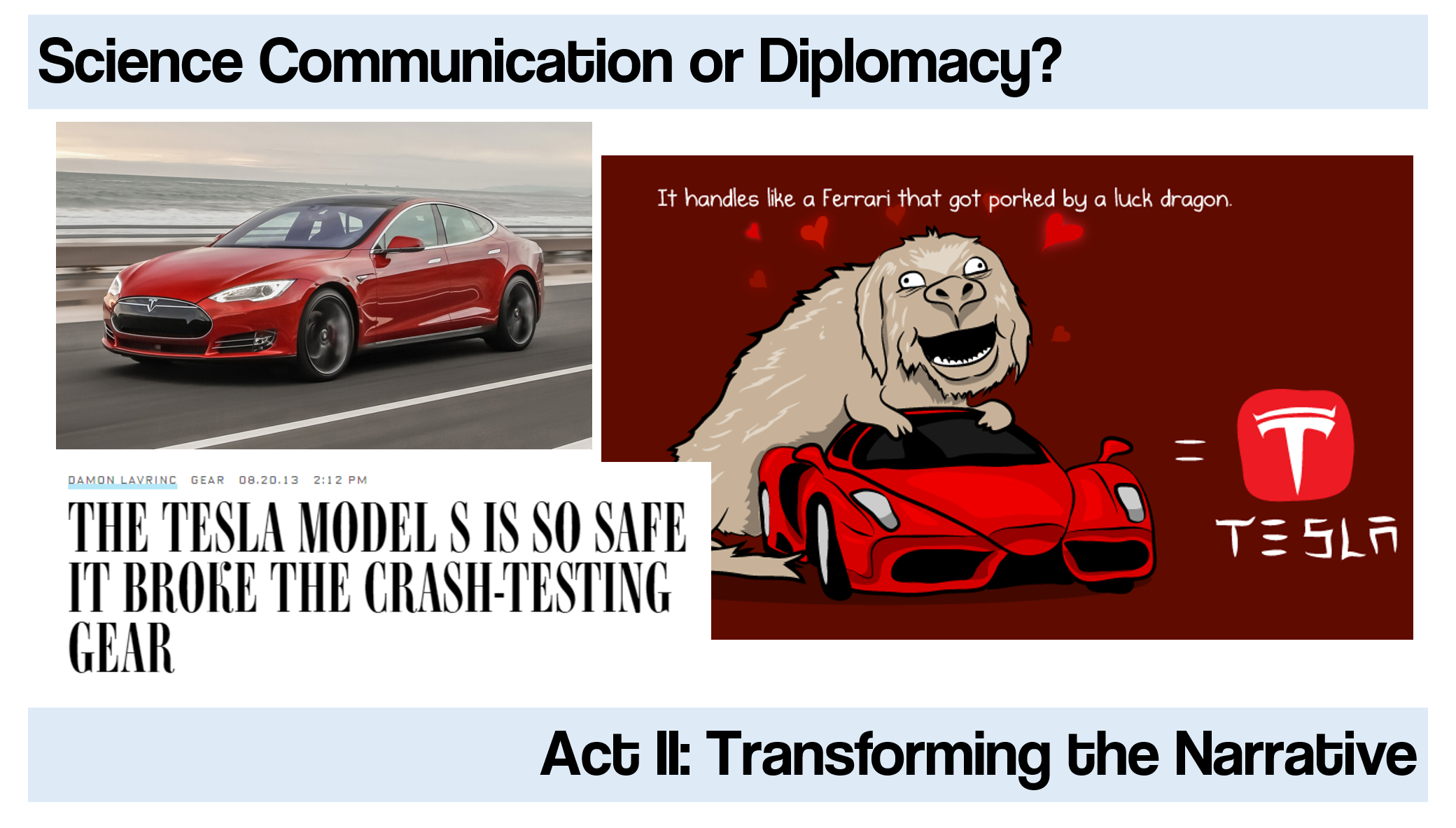

So I’m going to tell you the story of Tesla. Environmentalist have been trying to get electric cars on the road for decades and electric cars have actually been around longer than gas-powered cars. But they didn’t catch on. And they didn’t catch on for a lot of reasons–they didn’t perform great, their range was short, and car enthusiasts–the most enthusiastic of which become automotive journalists–were never particularly impressed. The environmental angle wasn’t sexy, it didn’t move their gears. And cars, especially in the US, are a visceral, physical, emotional things. They help define our identity. The great American road trip, the freedom of the road, the roar of a muscle car, these are deeply embedded in the national psyche. People “got” that electric cars could be better for the environment, but it didn’t matter. It wasn’t an education issue. It wasn’t a deficit model.

And, as an aside, if I haven’t made it clear, throw out the deficit model. It shouldn’t be in your outreach toolbox. At best it’s obvious. More often it’s patronizing to your audience. And, at worst, as is the case with climate change, it’s actively counter-productive. The only deficit you should focus on is your deficit in understanding your audience.

So what did Tesla do? They made an $80,000 luxury car that just happened to be electric. And because electric motors perform better than combustion engines on almost all measures, they made it fast. It can do 0 to 60 in 3.2 seconds. It has a setting called “Ludicrous Mode”. And oh, it’s electric, but it also handles like a Ferrari. And just for good measure, it’s so safe that when it was crash tested, the car survived and the crash test equipment broke.

Now, if you listen to Elon Musk talk about his vision for Tesla, it’s all about sustainability and phasing out combustion engines, and reducing carbon emissions and saving the world. But I challenge you to find any promotional material from Tesla hyping their car as the environmental choice. They transformed the narrative and brought their product to a cohort that would have otherwise wanted nothing to do with it.

That’s what I want us all to think about today as we gather and discuss this online ocean ecosystem that we’re building together. How do we make our outreach not just good, but transformative.

And fortunately, in the ocean community, we have a model to emulate.

Be like Jacques.

Jacques Cousteau did a lot of important things for the ocean. For many of us, he was our first introduction to the sea. He created documentaries to inspire. Throughout his career he evolved into a passionate advocate for the ocean and he trained three generations to love the ocean as he did.

But that’s not transformative. What’s transformative is what he gave us, and what he gave us was the Aqualung. It was a tool that allowed us to enter the silent world with him. That allowed us to take what he had done and build on it, to carry it forward into the future. To transcend the work of a single man.

And because of this, his work resonated far beyond the traditional audience for the ocean.

This a quote from Joel Salatin. He’s a self-describe lunatic farmer. An evangelical anti-government libertarian who thinks the EPA is a criminal organization and the Endangered Species Act is treason. And in a book about starting a small farm under the crushing weight of big government and the oppression of the US Department of Agriculture, in a passage that has nothing at all to do with the ocean, he says this:

“What if Jacques Cousteau had been afraid of risk? Would my generation have grown up with such a fascination toward the ocean and its cornucopia of life forms?”

This is someone who is almost certainly not on any of your SONARs for audience engagement, and yet the lessons of Cousteau are so deeply embedded that he accepts them as the de facto truth for his entire generation.

It does not get more transformative than that.

So how do we make our outreach transformative? It takes creativity, the willingness to try something new, maybe even dangerous; this is Oceans Online, so we’re talking about taking advantage of the technology that increasingly permeates every facet of our work; and, most importantly, it takes inclusivity. You can’t engage a new or unexpected audience by building barriers. And the most effective way to be inclusive is to give people the tools to take your work and make it their own.