Centuries of exclusion have resulted in a tangible human diversity deficit, where the diversity of oceanographers does not represent the global diversity of people impacted by ocean processes. Let’s explore the history of ocean science to understand how it ties into and influences the lack of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in modern day oceanography.

Race and Science

At this stage I think we all recognize that race is a social construct, it’s a myth. Racism, however, is a stark reality. An uncomfortable truth. A pervasive and seemingly unsolvable issue that plagues society. Science has a long and complicated history with race and racism (Norrgard 2008, Saini 2019).

The picture above represents the debates in the late 1700s which theorized that existing human beings had evolved from two or more distinct origins in light of their physical differences. This premise led to the production of a rigid set of racial categories and a hierarchy which identified White people as a superior race and separate to any other race.

Now, the pursuit of science is a shared experience, but for centuries science has been built on a legacy of excluding People of Color, and those from other historically excluded groups, from the scientific enterprise. Institutions and scientists have used research to justify discriminatory thinking, such as the nonsense by polygenist represented in the picture above, and have prioritized research outputs that ignore, and further disadvantage, excluded people; ocean science has not been an exception.

History of Modern Oceanography

From the earliest days of civilization, humanity has investigated the ocean and its processes as a means of survival and expansion. Obtaining marine resources requires skills such as fishing, sailing, and navigation that are only possible through intricate knowledge of the science behind ocean systems. Mastering this knowledge has furthered our understanding of the importance of the ocean in global processes and supported our efforts in ocean conservation and sustainability (Abulafia 2019). Conversely, obtaining this knowledge has also allowed societies to exploit ocean resources (McCauley 2023) and dominate and subjugate neighboring societies (Murphy 2016). Our understanding of the ocean is an accumulation of human knowledge, from all peoples, pieced and collated over centuries. However, the contributions from many non-white cultures have been all but forgotten (or intentionally erased), and what largely remains are descriptions of science through the eyes of Western explorers. The history of modern oceanography is thus permeated by imperialism, where maritime exploration was performed in the name of conquest, and the science relegated as a byproduct.

The earliest resemblance of modern oceanography begins with the nineteenth-century Navy officer and early ocean scientist Matthew Fontaine Maury. Maury, familiar to many in the oceanography and maritime communities, is widely regarded as the “father of oceanography” and “pathfinder of the seas” (Grady 2015, Hardy 2016). Maury was among the first to systematically collect and compare parameters like temperature and current information on a near-global scale, and his 1859 work, Physical Geography of the Sea, marked the first use of the English word “oceanography”. Historians also recognize that Maury’s scientific and naval work supported American expansionism. In this, Maury contributed to the long-standing effort to employ science in the service of imperialism, a strategy widely recognized by historians of oceanography (Reidy and Rozwadowski 2014, Smith 2018). Maury was also an ardent southern confederate during the US civil war, and he made vigorous and consistent efforts to support and extend the institution of slavery (Hardy and Rozwadowski 2020). These notions and ideas (imperialism, exclusion, discrimination), however reprehensible, are the foundation of modern oceanography. The depth to which racism exists within ocean science is highlighted in this foundation.

This is the insidiousness of racism in science; it underpins the very foundation from which we practice our discipline. It is with us even if we are ignorant of it.

DEI and Oceanography

At present, ocean science sits at a conundrum as it relates to representation. The lack of racial diversity in oceanography is itself an obstacle and impediment to diversification, because any student from a historically excluded group who considers entering oceanography understands that: they will be entering a predominantly white space; they will read many foundational papers written by well-known scientists with less-well-known problematic practices centered around imperialism and the subjugation of “othered” peoples; and they will be subject to macro- and micro-aggressions that undermine their sense of belonging.

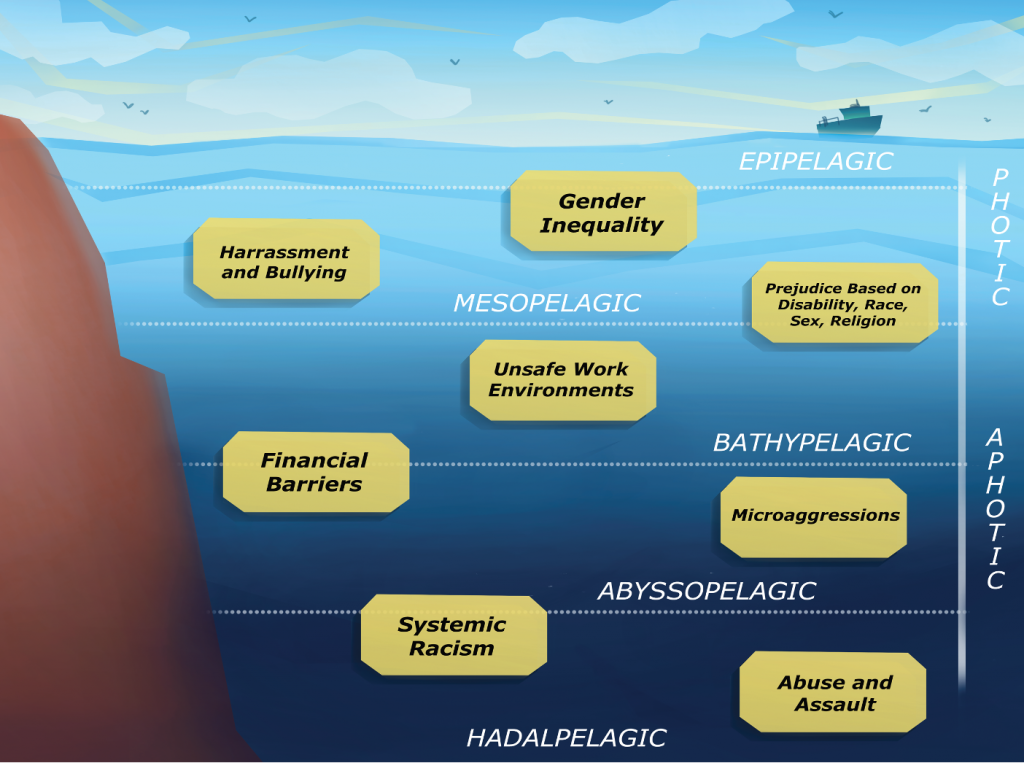

One part of the challenge is that visibility into DEI issues is variable, some issues are seen and more easily understood, whereas others are more obscure. The picture above attempts to represent this challenge conceptually through the use of the photic and aphotic zones in the ocean. The photic zone, for example, includes easily understood, well-established issues like binary gender or harassment and bullying, while the aphotic zone includes issues in DEI that are more often overlooked or dismissed, such as systemic racism and financial challenges. As a community, the more issues that we can bring into the light, that is to say, the more issues that can be shifted from the aphotic zone to the photic zone, the higher probability we have at addressing and resolving these issues. Addressing and discussing issues around DEI can be uncomfortable and as humans we tend to avoid things that make us uneasy. However, relegating issue from the light of day, will only maintain the status quo, and does not move us any closer to building a more inclusive and equitable scientific community.

So we know we have a problem, but where do we go from here?

Moving Forward

The foundation on which modern ocean science is built is imperialistic and racist. How then, do we reform a society that was built from a power structure of oppression? We must first start with acknowledging the problem. History cannot be changed, and efforts to build a more inclusive and equitable scientific community should not be done with a view of righting the wrongs of the past. Instead, efforts should be undertaken with an earnest view that diversity, equity, and inclusion are the best path forward for the scientific community and the endeavor of science. There is ample evidence that diverse groups are more effective at solving issues and tackling challenges (Hong and Page 2004, Hofstra et al. 2020), and scientists understand the importance of diversity in the populations and systems they study. If diversity is a measure of a healthy and functioning ecosystem, what does the current demographic composition of the scientific community say about its state? The first step toward building a more diverse and equitable and anti-racist scientific community is to know our history, name our bias, and move forward with intention.

To learn more about Oceanography’s Diversity Deficit, check out a paper we recently published in the journal Oceanography, which identifies the six major challenges contributing to oceanography’s diversity deficit, and recommends solutions that individuals, mentors, professional societies, funding agencies, and institutions can take to tackle the issue of a lack of DEI in oceanography.

References

Abulafia D (2019) The Boundless Sea: A Human History of the Oceans. New York: Oxford University Press. 219 pp.

Grady J (2015) Matthew Fontaine Maury, Father of Oceanography: A Biography, 1806–1873. McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 353 pp.

Hardy PK (2016) Matthew Fontaine Maury: Scientist. International Journal of Maritime History 28: 402–410.

Hardy PK, Rozwadowski HM (2020) Maury for modern times: Navigating a racist legacy in ocean science. Oceanography 33: 10-15.

Hofstra B, Kulkarni VV, Munoz-Najar Galvez S, McFarland DA (2020) The diversity-innovation paradox in Science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117: 9284-9291.

Hong L, Page SE (2004) Groups of diverse problem solvers can outperform groups of high-ability problem solvers. Proceeding of that National Academy of Sciences. 101: 16385-16389.

McCauley DJ (2023) The future of whales in our Anthropocene ocean. Science 9(25): 1-3.

Murphy KS (2016) The slave trade and natural science. In: Oxford Bibliographies in Atlantic History, ed. Trevor Burnard (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016). DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199730414-0266.

Norrgard K (2008) Human testing, the eugenics movement, and IRBs. Nature Education 1: 170.

Reidy MS, Rozwadowski HM (2014) The spaces in between: Science, ocean, empire. Isis 105: 338–351.

Saini A (2019) Superior: The Return of Race Science. Beacon Press, 256 pp.

Smith JW (2018) To Master the Boundless Sea: The US Navy, the Marine Environment, and the Cartography of Empire. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 280 pp.