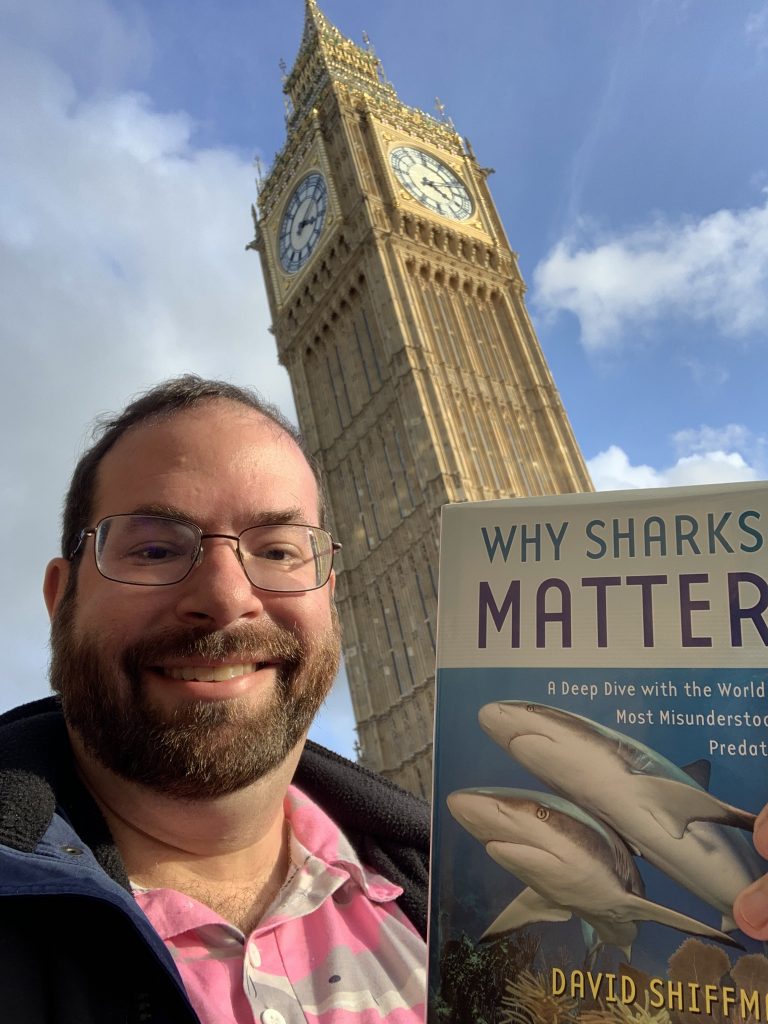

One year ago today, my book “Why Sharks Matter: A Deep Dive with the World’s Most Misunderstood Predator” was released. Science moves (relatively) rapidly and changes often, with new discoveries every day, and the conservation landscape is similar. This means that it is impossible for anything written about these topics at a discrete moment in time to remain accurate forever.

So, in the interest of accountability, in the interest of continuing to make my book useful for public education about shark science and conservation even as the science and policy landscape changes, and in the interest of keeping notes for myself for any future updated versions of the book, I have been keeping track of things that I wrote at the time that are no longer true, or weren’t quite right at the time. (Please note that some of these facts and figures were already out of date at the time the book was pubished, but that was well after the final text was turned in).

More species are threatened with extinction now. Why Sharks Matter uses the statistics on which species of sharks and their relatives are estimated or assesed with extinction from Dulvy et al. 2014, which found that about 1 in 4 species of sharks and their relatives are considered threatened. A newer update to this paper (Dulvy et al. 2021,) which was pubished just as I was finishing this chapter of Why Sharks Matter, found that the latest figures are closer to 1/3 of species threatened. Table 5.1 of Why Sharks Matter, lists all shark species assesed as Endangered or Critically Endangered by the IUCN Red List as of the time that I wrote the text of that chapter. A search this week found more species with that alarming assessment than I reported at the time. (It’s worth noting that some of this is what the Red List calls “non-genuine change,” which means the species isn’t actually worse off than it used to be, we just have more data now. But some of it is “genuine change,” which means the species is actually worse off than it used to be.”

Vending machines don’t kill more people than sharks do these days. My obligatory list of things that are more dangerous than sharks in Chapter 2 includes a discussion of the dangers of vending machines. This prompted a surprisingly rigorous interview with Slate magazine about this statistic. It turns out that though almost all shark scientists who talk to the public use this statistic, it isn’t really true anymore thanks to some long overdue safety upgrades to vending machines. It did used to be true, and I still hear it all the time, but this is a public safety win that I suppose we should celebrate. (It is worth noting that I don’t know anyone who has been seriously injured by a shark and I do know two people who have been seriously injured by vending machines.)

More species of sharks are listed under CITES Appendix II now. At the 2022 Conference of the Parties of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, the number of species listed under Appendix II greatly increased under a proposal I explained for Hakai. I also included the aside “sorry, Potamotrygon freshwater stingrays” on page 149, but protections for this group have since been adopted!

One of my featured non-profits has changed their name. Chapter 9 of Why Sharks Matter includes a list of great environmental non-profits who work in the shark conservation space. One of those non-profits is PADI Project Aware, which has since changed it’s name to the PADI AWARE Foundation. At least as of today, googling “PADI Project Aware” takes you to their new site, but still, I should note here that the name has changed.

More of the ocean is highly protected now. In my Chapter 7 discussion of marine protected areas, I noted that as of the time I finished that chapter, 2.6% of the ocean was considered fully or highly protected by the Marine Conservation Institute’s Marine Protection Atlas. I just checked today, and good news folks, we’re now up to 2.9%!

A US Shark Fin Ban is now law. At the time I wrote Chapter 7, I noted that this law, which I have long opposed, was still being debated. It has since become law in the United States after being included as part of a 2022 defense spending bill.

Some things from the book that were just not quite right.

I am pleased to report that despite covering a wide variety of complex discussions that are the subject of very heated professional arguments, I’ve only received two requests to change facts that I reported because they’re not quite accurate.

In Chapter 6, I noted that NOAA Fisheries was considering listing only some Distinct Population Segments of Oceanic Whitetip Sharks under the Endangered Species Act, but the proposal was for the whole species not just some DPSs.

And when discussing fin to carcass ratios as a way to restrict shark finning, I noted that the fin to carcass ratio for smooth dogfish in the United States was 12%, which was “not based on smooth dogfish biology or really any kind of scientific evidence.” It has since been pointed out that there is some scientific evidence, it’s just hotly disputed, with one expert I asked about this calling it “bull shark shit.”

There are also four typos, which I will not be discussing further. Your welcome.

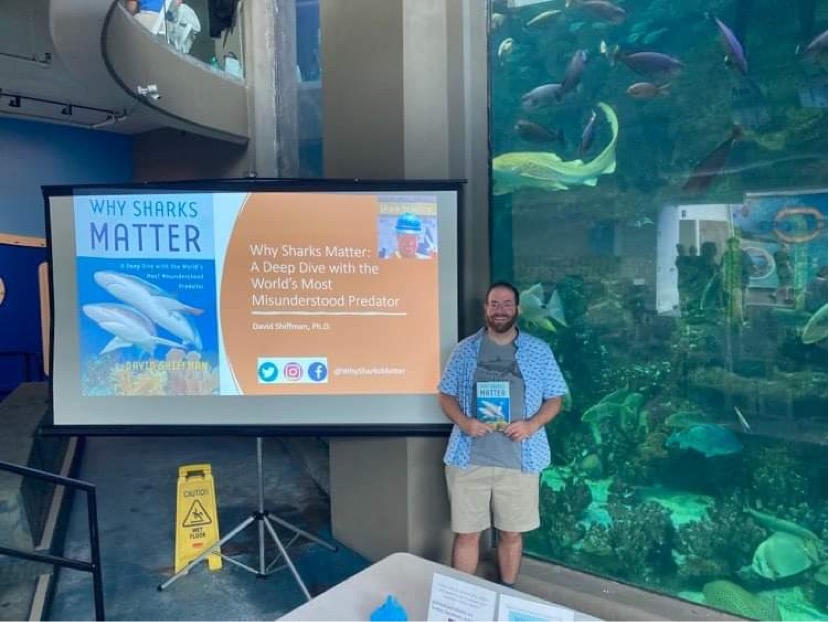

Thanks for reading, and thanks for keeping me honest! Writing this book, and then going on a 50-city international book tour to talk about it, has been the professional adventure of a lifetime. I’ll always be grateful to everyone who generously shared their expertise with me when I was writing and editing the book, and to everyone who helped make my tour a reality.