At the beginning of 2024, I made a commitment to make it the year of the OpenCTD. A CTD is an oceanographic instrument that measures salinity, temperature, and depth. It is an essential tool in the conduct and marine scientific research. Access to CTDs often present a barrier to communities and knowledge seekers interested in studying their local waterways. The OpenCTD is a low-cost, open-source alternative to conventional CTDs which can be built for a fraction of the cost and maintained by the end user.

This project, which has been my passion for the last 10 years, was just on the cusp of becoming a viable, sustainable program. It just needed one big push. So I forwent other work, took a year-long sabbatical from the deep-sea mining world, put my research grants on hold, and focused, (almost) exclusively, on getting the OpenCTD done.

What a year it was! Beginning with the long-awaited publication of the OpenCTD paper and the finalization of the fourth edition build manual, we dropped a ton of resources onto the open-science community. I presented our results at Oceans 2024 in New Orleans and met up some wonderful friends and collaborators who have helped make this project a success.

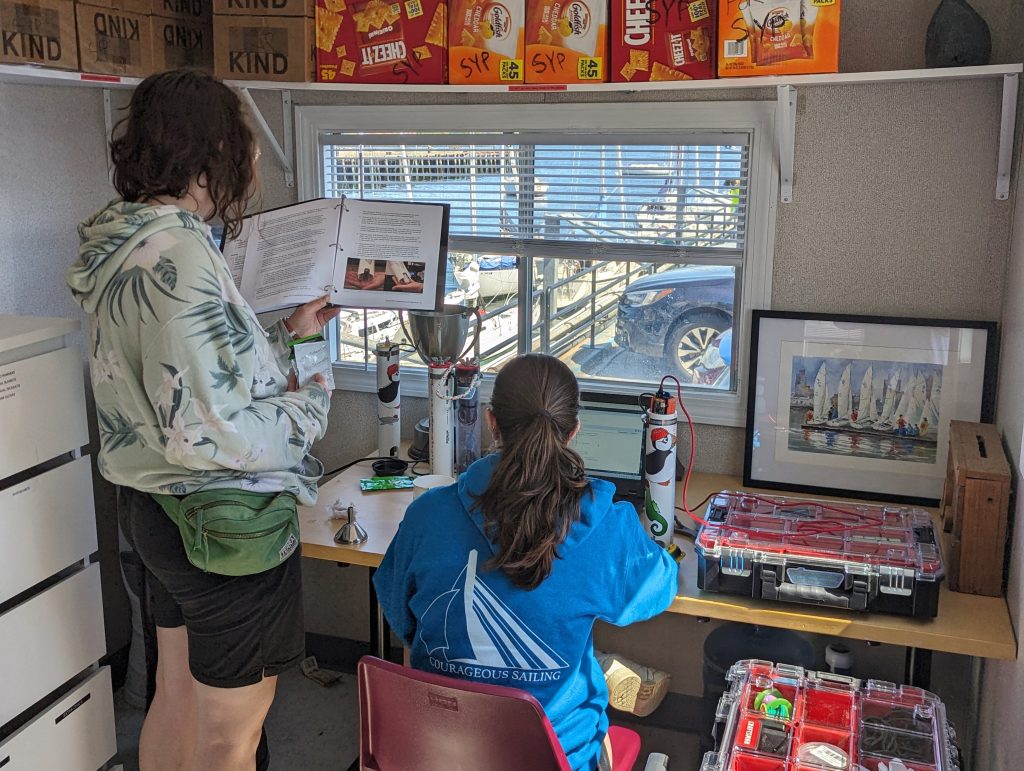

In May, I was off to Boston to train the teachers at Courageous Sailing on how to run their own OpenCTD classes while building several units for the program.

In September, I went down to North Carolina for the most ambitious OpenCTD project to date, deploying 25 OpenCTDs across Albemarle Sound to track the energy of internal waves in collaboration with the Coastal Studies Institute. This was the biggest and most involved workshop to date and I left inspired by the students and faculty at CSI and overflowing with ideas.

A month later, I was off to Alaska for the capstone program, delivering a BOEM-sponsored train-the-trainer workshop to educators in Homer who would then take their CTD kits to classrooms in remote communities. I can’t even begin to describe how incredible this short week in Home was. Teaming up with the incredible people at Educational Passages, we starting fleshing out the plans for what could become a semester long intensive program in oceanography and ocean technology for high school and college students, using CTDs, drifters, an miniboats in an adaptive conservation technology program.

That wasn’t it for Alaska, though. Following the Homer program, I was off to Fairbanks to teach an OpenCTD workshop with the University of Alaska, Fairbanks. In addition to everything else, we also built and deployed the first freshwater OpenCTDs, capable of taking minute salinity measurements to help delineate glacial runoff from meltwater from stormwater from industrial and agricultural discharge.

I loved my time in Alaska, but holy mola was it cold (especially Fairbanks). Fortunately, I had one final trip in the pipeline. I ended the year teaching the final OpenCTD workshop at the H Lavity Stoutt Community College in the British Virgin Islands. As the first international OpenCTD workshop, this was a test for the ultimate vision of the OpenCTD – creating local expertise in communities that need oceanographic data and creating programs that can thrive independent of my involvement.

Over the last year, I met with hundreds of students and collaborators and oversaw the construction of more than 40 OpenCTDs. I am awed by the hunger to understanding the ocean I’ve seen from people from across the world. OpenCTD began with a simple vision: if the stewardship of the ocean is all our responsibility, the tools to study and understand that ocean must be available to everyone.

If the stewardship of the ocean is all our responsibility, the tools to study and understand that ocean must be available to everyone.

This year, I wrote several articles about the OpenCTD and the projects we’re running:

- It is your ocean. You should have access to the tools to study it.

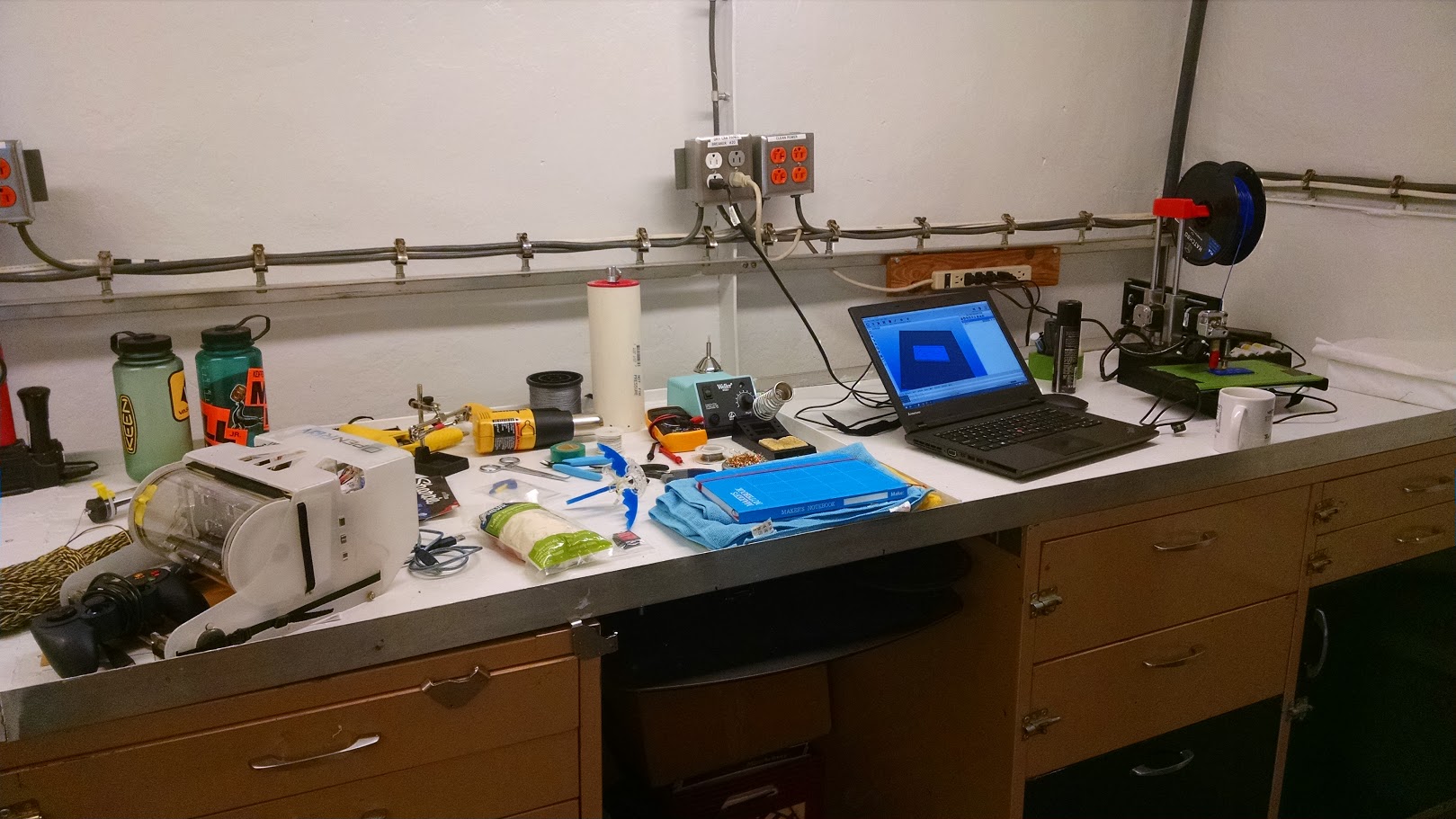

- Independent ocean science requires local support: testing our mobile OpenCTD factory.

- A calling card for oceanographers

- Did you calibrate you CTD today?

- Comparing the OpenCTD to a YSI Castaway

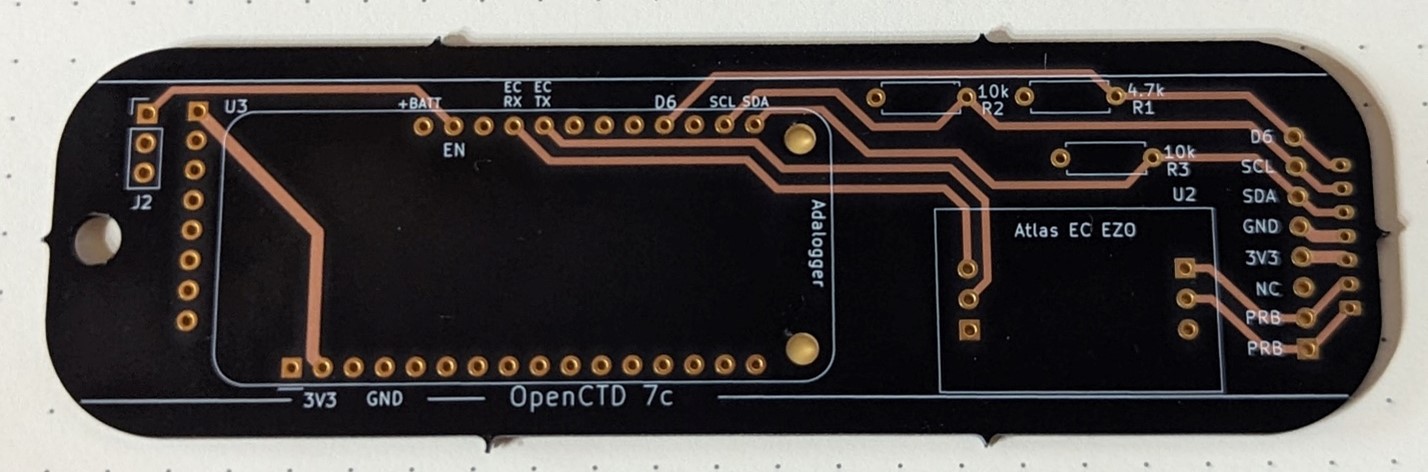

What’s amazing is that there still so much work left to do. Spending a year focused on every nuance of the project opened my eyes to the myriad ways we could make an even better OpenCTD. Enhanced noise isolation on the conductivity probe, replacing the battery of three temperature sensors with a single, high quality platinum probe, breaking away from the break-out board to make our own pressure sensor break out, all of these are the obvious next steps that could be done without increasing the cost of the OpenCTD kit.

And then there’s the housing. I think we have the best housing you can build with off-the-shelf hardware store parts. We have OpenCTDs that have regularly done casts to 50 meters or more, throughout a season, without flooding or failing. But we’ve also had OpenCTDs that fail on their first cast. Adding the DIY pressure chamber dramatically improved the success rate of the housing, but even that doesn’t cover all deployment scenarios. I suspect there are folks who would gladly add an extra $80 to the cost of the OpenCTD for a more reliable housing.

So that’s my roadmap. 2025 cannot be exclusively OpenCTD work like 2024 was. Financial sustainability for the project is still out of reach, but making those four big improvements is my goal for the OpenCTD in 2025.

Here’s where I make my pitch: The OpenCTD has been crowdfunded since crowdfunding was a thing. Patreon is the platform that keeps this program rolling. We’re creeping our way towards making a self-sufficient model for the OpenCTD, but because we are open-source and committed to keeping the cost as low as possible, I suspect there will always be some form of community support to keep the project rolling.

If you value the OpenCTD and the work we do, please subscribe to my Patreon. There are a few OpenCTD specific tiers, but if you drop a note that you only want your contributions to go towards the OpenCTD program, I will make sure that that happens, regardless of the funding tier.

And, we have stickers, so many glorious stickers.